Overview

Water is a vital resource in our everyday lives and in the environment around us. We use it in our households, industries and food production, in cultural practices and for maintaining and restoring the environment.

Nearly all the water we use comes from rainfall. Rainfall in NSW is highly variable, so we need to capture and store it for later use. We also need to use it efficiently and wisely to make sure it is available for all users.

Climate change makes this harder in two ways – higher temperatures increase water use and the severity of drought, and rainfall becomes more variable and likely to decrease.

Water management is also challenged by our increasing population.

Removing too much water from our rivers, streams and groundwater systems can reduce their environmental health. Putting water back at the wrong time, at the wrong temperature or with different amounts of nutrients can harm plants and animals.

We need to manage our water use to ensure aquatic environments have the water they need at the right times This will protect the environmental and cultural values of rivers and groundwater systems.

How we use water

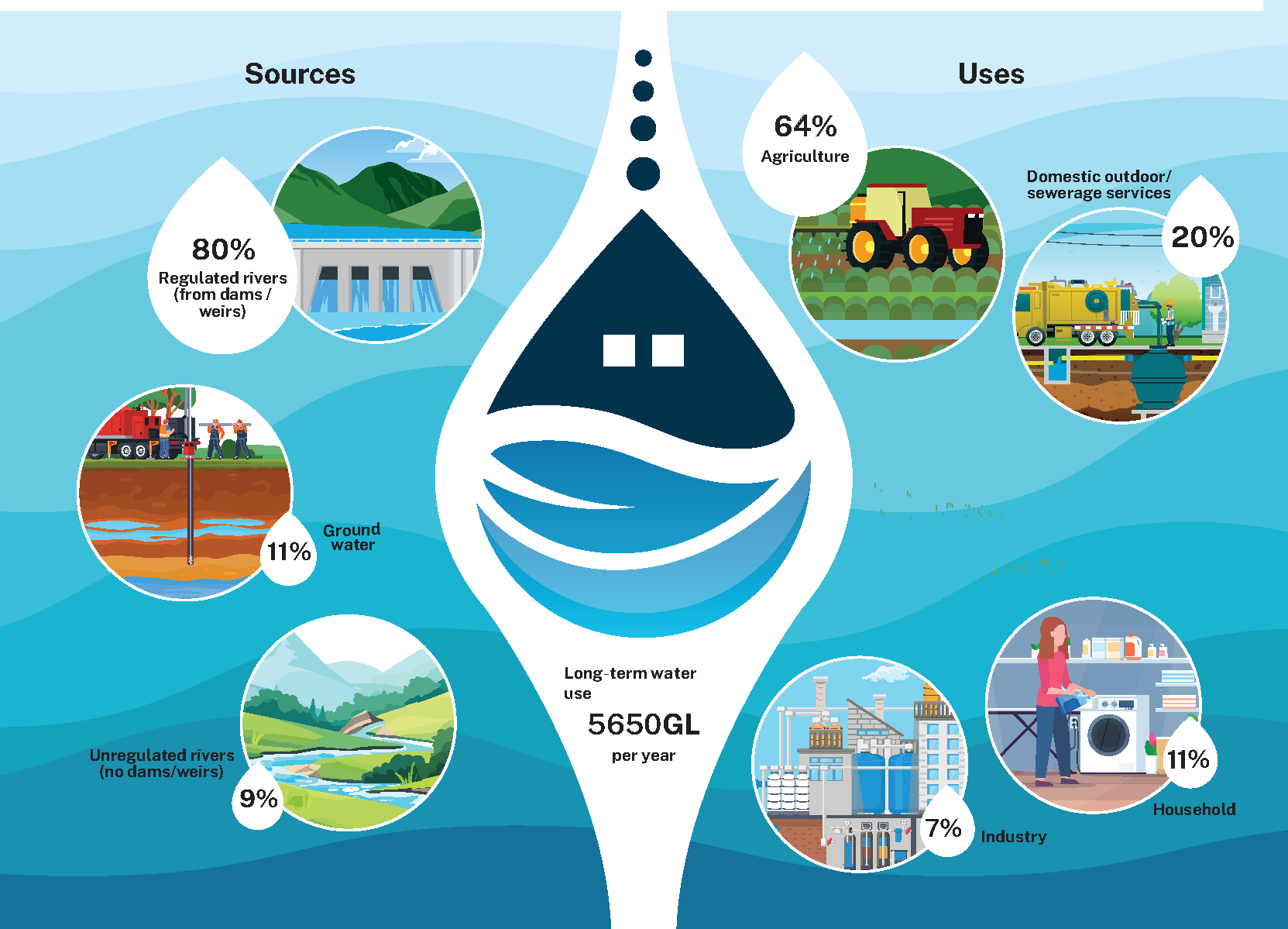

In NSW, we used on average about 5,650 gigalitres (GL) of water per year from 2014–15 to 2023–24 (). This varies annually depending on water availability in rivers, as less is available during drought.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics uses surveys to find the main uses for water in Australia. Their data for the years 2014–15 to 2021–22 showed the main uses for water in NSW were:

- agriculture, forestry and fishing industry, about 64%

- electricity generation, gas production, water supply losses and waste services, about 16%

- households, about 11%

- other industry, about 7%

- mining about 2% ().

Water is lost from storages and the distribution system due to evaporation and leakage.

Most of the water supplied in NSW is extracted from rivers, surface water runoff and groundwater systems (see Figure P3.1). A small fraction comes from desalinated seawater. Some water is recycled from homes and industries to be used on parks and gardens, and by industry. Sydney Water is developing purified recycled water by treating recycled water further to meet drinking water standards.

Excluding supply to Sydney, in 2022–23 about 74% of this water came from regulated rivers. Flows in these rivers are controlled by large dams and weirs. Of the remainder, just under 17% was sourced from unregulated rivers (rivers without large dams or weirs) and about 9% from groundwater ().

See the and topics for more information.

Figure P3.1: Conceptual model of water use paths

Environmental impacts

Water use patterns and practices in NSW have contributed to the degradation of aquatic ecosystems. Changes to the timing, amount and temperature of water in our streams have caused significant biodiversity loss and declining ecosystem health, particularly in the Murray–Darling Basin.

A striking example of this is the occurrence of mass fish deaths when oxygen levels in the water fall too low. Two significant such events occurred in the Darling–Baaka River in the last three years ().

Various human activities alter the natural properties and composition of water. The addition of harmful chemicals can cause both short- and long-term impacts on plants and animals.

In addition, water use and infrastructure in urban areas affects aquatic ecosystems through:

- increased stormwater runoff, which adds pollutants

- higher water flows, which erode banks and deepen channels

- the building of artificial waterways that don’t allow plants and animals to grow

- discharges from sewage treatment plants, which change flow rates, temperatures and amounts of nutrients.

See the and topics for more information.

How we manage water

Water is regulated in NSW through a system of water licences and allocations for every water source.

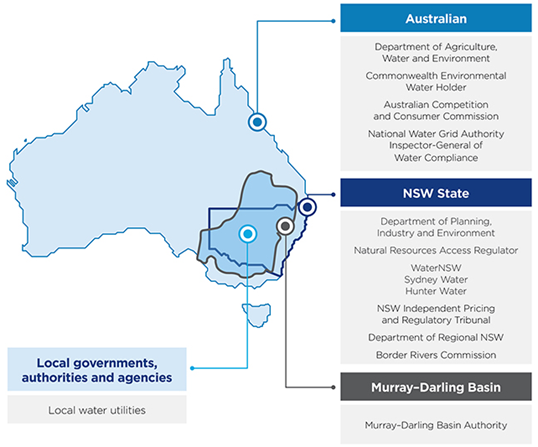

Many agencies manage water in NSW (see Figure P3.2). These include:

- the Australian Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

- the NSW Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water

- WaterNSW

- the Murray–Darling Basin Authority

- local water utilities in regional towns

- metro water utilities (Sydney Water and Hunter Water).

NSW Health endorse the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines.

Water management is becoming harder as NSW’s climate changes. Rainfall is more variable. Higher temperatures have made droughts more severe and more rapid. Less water is available and our storages are used up sooner.

Figure P3.2: Major agencies and organisations involved in water regulation in NSW

Notes:

Created prior to 2023. Since 2023, some entities listed above have changed names.

The Water Management Act 2000 and various regional Water Sharing Plans provide the legal framework for water licencing, allocations, water sharing, environmental flows and water trading.

Water is allocated for licence holders annually. Allocation depends on various factors, including availability and prioritisation.

See the WaterNSW website for more information on how water is allocated.

Water for the environment is specifically set aside to sustain and restore natural waterways. It is essential to improving environmental, economic, social and cultural outcomes.

See the water for the environment website for more information.

Aboriginal people, communities and organisations in NSW can apply for an Aboriginal cultural water licence for up to 10 megalitres (ML) to provide water to care for cultural values or maintain cultural practices.

The NSW Water Strategy underpins the State’s approach to improving the security, reliability and quality of water resources while balancing the need to supply water in order to:

- provide a healthy environment

- secure water resources for human use

- support Aboriginal cultural outcomes

- enable economic function.

A combination of public health and water quality legislation and policies ensure high-quality drinking water in NSW.

NSW manages water resources by using a range of legislative instruments, strategies, policies and plans (see Table P3.1). Their purpose is to provide safe water to people, businesses and industries in ways that minimise impacts on the environment.

Table P3.1: Current key legislation and policies for the management of water and its use

| Legislation or policy | Summary |

|---|---|

| Commonwealth Water Act 2007 | Makes provision for the management of the water resources of the Murray–Darling Basin, and to make provision for other matters of national interest in relation to water and water information, and for related purposes. |

| NSW Water Management Act 2000 | Recognises the need for allocation and provision of water for environmental health of rivers and groundwater. It provides water licence holders with secure access and trade opportunities. |

| Public Health Regulation 2012 | Regulates drinking water standards. |

| Australian Drinking Water Guidelines 2011 | Endorsed by the NSW Government and used to assess safety of water for drinking. |

| Commonwealth Basin Plan 2012 | Sets out objectives and outcomes to manage the water resources in the Murray–Darling basin. Legislative instrument made under subparagraph 44(3)(b)(i) of the Commonwealth Water Act 2007. |

| National Water Quality Management Strategy | Assists water resource managers to understand and protect water quality so that it is ‘fit for purpose.’ |

| NSW Long-term Water Plans | As part of NSW’s commitments under the Basin Plan, NSW has developed long-term water plans for nine NSW river catchments which guide and inform water management (including water for the environment) for environmental outcomes over the long term by setting objectives, targets and watering requirement for plants, waterbirds, fish, other species such as frogs over 5-, 10- and 20-year timeframes. |

| NSW Water Strategy 2021 | A 20-year, statewide strategy to improve the security, reliability and quality of the State’s water resources over the coming decades. Sets the overarching vision for twelve regional and two metropolitan water strategies, tailored to the individual needs of each region in NSW. Implementation plan 2022–24 sets out current work, 42 actions across 7 priorities. |

| Water Sharing Plans | Provides rules for the allocation and sharing of water between water users and environmental needs. Plans are provided for different regions and water sources within NSW. |

Notes:

See the Responses section for more information about how is being addressed in NSW.

Related topics: | | |

Status and trends

Water use indicators

Indicators are chosen to represent how successful we are in delivering safe water to support the environment, industry and households. We need to store water so it can be delivered when needed, while also making sure there are effective systems in place for sharing it. Minimising use is an important part of making sure we have enough.

Table P3.2 shows water use indicators relating to environmental use.

- Proportion of water extraction covered by water sharing plans remains stable owing to high surface water availability from relatively high rainfall in 2021–24 (see Extraction from NSW rivers).

- Allocation of water for the environment significantly improved from previous years from ‘moderate’ to ‘good’ (see Water for the environment).

Table P3.2: Water use indicators – environmental use

| Indicator | Environmental status | Environmental trend | Information reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of water extraction covered by water sharing plans | Stable | Good | |

| Allocation of water for the environment | Getting better | Reasonable |

Notes:

Indicator table scales:

- Environmental status: Good, moderate, poor, unknown

- Environmental trend: Getting better, stable, getting worse

- Information reliability: Good, reasonable, limited.

See to learn how terms and symbols are defined.

Table P3.3 shows indicators relating to water supply.

- Proportion of the metropolitan and regional water supply meeting national guidelines is stable, continuing to meet national guidelines and provide communities with high-quality water that is safe to use (see Urban water).

- Minimising total and per person water use in metropolitan and regional centres is moderate and use is decreasing in urban areas meaning the trend is getting better (see Urban water).

- Water recycling (both major utilities and local water utilities) is increasing, however, recycled water still provides only a small fraction of the water supply (see Other water sources).

Table P3.3: Water use indicators – supply

| Indicator | Environmental status | Environmental trend | Information reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of the metropolitan and regional water supply meeting national guidelines | Stable | Good | |

| Minimising total and per person water use in metropolitan and regional centres | Getting better | Good | |

| Water recycling – major utilities | Stable | Good | |

| Water recycling – local water utilities | Getting better | Good |

Notes:

Indicator table scales:

- Environmental status: Good, moderate, poor, unknown

- Environmental trend: Getting better, stable, getting worse

- Information reliability: Good, reasonable, limited.

See to learn how terms and symbols are defined.

Storage volumes

Water storage in NSW is highly dependent on rainfall.

The amount of water stored in dams across NSW decreased from 2017 into 2020 because of below-average rainfall (see Figure P3.3). By February 2020, combined total regional dam levels reached their lowest point since 2007, with some storages facing supply issues.

Significant rainfall in February and March 2020 increased dam levels in the Greater Sydney region to about 82% by the end of March. Yet these weather events increased dam levels in the regions only marginally, to about a quarter of capacity.

Figure P3.3: Accessible volumes of water (GL) in major NSW dam storages, as at 30 June 2024, from 2015 to 2022

Storage throughout NSW remained above 80% until February 2023 (see Figure P3.4). Spilling occurred in some areas at the end of 2022.

Rainfall can vary significantly within NSW resulting in marked differences in dam storage levels.

Figure P3.4: NSW storage level profiles between 2000 and 2024

Notes:

Metro Dam includes Cataract, Cordeaux, Avon, Woronora and Nepean dams. Regional storage information excludes Glen Lyon and Oberon dams owing to incomplete data.

Extraction from NSW rivers

Climate variability affects water extraction

Figure P3.5 shows water use by licensed users from 1999–2000 to 2022–23 taken from the major NSW inland regulated river valleys (Gwydir, Namoi, Macquarie, Lachlan, Murrumbidgee and NSW Murray).

Much less water was used at the end of the Millennium Drought (2001–09) and during the 2017–20 drought. Dry conditions eased in 2020 and wetter weather occurred in 2021–23. This replenished storages and enabled full allocations for licence holders.

Water use has decreased from 1999–2000 to 2022–23.

Figure P3.5: Water use (GL) by licensed users in major NSW regulated valleys from 1999–2000 to 2022–23

Notes:

Some ‘water remaining’ is lost to evaporation, seepage and other transmission losses. While in the system, this water may have some benefit to the environment, depending on the duration, volume and timing of its flow.

Water use figures refer to licensed account usage. Water licences are held for town water supply, agriculture and the environment.

Floodplain harvesting is not included in the charts.

Total flow and observed diversions in the Murrumbidgee Valley are influenced by water released from the Snowy Mountains Scheme. These releases have greatest relative contribution in dry years. Development in the valley reflects this inter-valley transfer.

NSW Border Rivers data before 2009 were estimated from Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal submissions.

Figure P3.6 (a–e) shows water usage for each of the five major NSW inland regulated river valleys (excluding the Murray) as the amount of water extracted and the amount remaining in the river after extraction. Percentages for each are listed. The graphs show the large variation in water supply from rainfall and that it can change quickly.

Water demand increases when rainfall is lower but this also reduces water flowing into our rivers. Water sharing plans set out how much water will be distributed. NSW limits the impact of dry conditions on river systems by releasing water from storage, by limiting the amount of water extracted and by specifically allocating water to the environment.

The graphs show the differences that can occur in water availability among these five river valleys over the same period due to variable rainfall across the State.

In 2016–17, more water was available in the Macquarie (6c), Lachlan (6d) and Murrumbidgee (6e) from higher-than-usual rainfall. In contrast, the Gwydir (6a) and Namoi (6b) experienced median rainfall.

See the topic for more information about rainfall patterns.

Figure P3.6 (a–e): Amount of water (GL) in rivers from major inflows and water remaining after extraction in the major NSW regulated valleys, 1999–2000 to 2022–23 (from north to south of NSW)

a) Gwydir

b) Namoi

c) Macquarie

d) Lachlan

e) Murrumbidgee

Notes:

The NSW Border rivers and NSW Murray River valleys are not included in this set of charts.

Some ‘water remaining’ is lost to evaporation, seepage and other transmission losses. This water may have some benefit to the environment depending on the duration, volume and timing of its flow.

Water use figures refer to licensed account usage, including general security, high security, conveyance, water utilities, domestic and stock and supplementary access. Water licences are held for town water supply, agriculture and the environment.

Floodplain harvesting is not included in the charts. Diversions include licensed environmental water use.

The data for each valley represent total water available and are taken from a representative gauging station downstream of major tributary inflows and upstream of major extractions.

Total flow and observed diversions in the Murrumbidgee Valley are influenced by water released from the Snowy Mountains Scheme. These releases have greatest relative contribution in dry years. Development in the valley reflects this inter-valley transfer.

Water for the environment

Water for the environment is allocated through water sharing rules and water licences held by both the NSW Government and the Australian Government. Water for the environment is allocated to sustain and improve the health of rivers, wetlands and floodplains.

NSW water for the environment shares have grown from 2005–06 to 2023–24 from water licence purchases and the creation of new entitlements through water savings infrastructure projects (see Figure P3.7).

NSW has a total of 2,553GL of licensed water for the environment (see Figure P3.7). This is made up of:

- 331GL NSW Government holdings within regulated rivers

- 15GL NSW Government holdings within unregulated rivers

- 571GL Living Murray holdings within regulated rivers

- 13GL Living Murray holdings within unregulated rivers

- 1,576GL Australian Government holdings within regulated rivers

- 47GL Australian Government holdings within unregulated rivers.

Figure P3.7: Growth in water for the environment shares in NSW (GL)

The volume of water for the environment delivered to locations across inland NSW was significantly higher during 2020–21 to 2022–23 than in the previous three years (see Figure P3.8).

Volumes ranged from about 279GL in 2019–20 to more than 1,300GL in 2021–22, the largest amount delivered since 2016–17. These large changes highlight how quickly water availability can change, owing to large, rapid reductions from drought and record-breaking high temperatures, and rapid recovery from high rainfall, which can cause flooding.

The delivery of this water promoted native fish breeding and movement, increased river and wetland connectivity, recharged groundwater reserves, supported native vegetation and provided important habitat for bird breeding events.

Figure P3.8: Water delivered to support the environment (GL)

Urban water

Urban water sources

Surface water provides more than 90% of the water for Sydney Water and Hunter Water and more than 80% for local water utilities. Other than during drought years, this has been the case since 2005–06.

Surface water comes directly from rain, so storage is critical to ensure water supply in the State’s variable climate. The predicted reduction in rainfall due to climate change means we need to plan our approach to supplying water to where it is needed. This includes considering sources for water, how much to store, and ways to minimise use including re-using water and reducing water losses.

Urban water use has been decreasing

Figure P3.9 shows declining water consumption per connected property.

Water consumption has been following a downward trend since 2005–06. The decrease in consumption was initially brought on by water conservation measures and user restrictions during drought. While wetter weather reduced demand, the continued reduction in water use suggests that people have continued some of the water conservation measures they adopted during the most recent drought.

Sydney’s residential water use was 18% lower in 2022–23 than in 2017–18, despite the end of enforced drought response measures from early 2020 (; ).

Figure P3.9: Annual per property residential water consumption for local water utilities, Sydney Water and Hunter Water from 2004–05 to 2022–23 (kL)

Notes:

This figure shows annual consumption per residential connection by each utility operational area.

For local water utilities, the figure is based on the median value of annual average residential consumption. Because the Hunter Water supply network interconnects with adjacent local water utilities, it can supply and receive bulk treated water from Central Coast Council and MidCoast Water.

Regional NSW had the greatest decrease (43%) because of water efficiency measures introduced during recent droughts.

See the Responses section of this topic for more information.

Drinking water quality is maintained

Drinking water in the State’s metropolitan areas and its regional cities and towns is routinely tested against the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines. The guidelines set limits on concentrations of particular contaminants, namely microbes (measured by concentrations of Escherichia [E.] coli), particular chemicals and aesthetics (colour, smell and taste).

In 2022–23, all utilities provided 100% of their population with water that met the guidelines for chemicals (), and all but one provided 100% of their population with water meeting guidelines for contamination with E. coli (Inverell achieved 99.9%).

In 2023–24, Hunter Water distribution system samples complied with the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines ().

Water provided by each of Sydney Water’s 13 delivery systems met the water guidelines ().

Impact of extreme climate and weather on water quality

Droughts, bushfires and floods affect not only water flow in catchments, but also water quality.

Drought in 2017–20 and bushfires in 2019–20 damaged vegetation in many drinking water catchments. Hot and dry weather was followed by heavy rains from 2020 to 2022, which caused flooding and significant runoff. This runoff carried greater amounts of sediments, pathogens and nutrients into rivers.

The runoff from burnt areas created significant challenges for water treatment and prompted an increased number of ‘boil water’ alerts (). ‘Boil water’ alerts decreased in 2023–24, but heavy rainfall was a contributing factor from December 2023 to April 2024.

Testing of water supply systems in remote Aboriginal communities in NSW showed continued problems with high levels of hardness, fluoride, turbidity and total dissolved solids ().

Other water sources

Recycled and desalinated water are not dependent on rainfall and help secure the State’s water supply by providing an alternative source. They currently contribute a small portion to the supply but can increase to help NSW become more resilient to variable climate.

Recycled water

Recycled water in NSW is supplied for non-potable (not drinkable) uses such as irrigation of playing fields, parks and golf courses, and for industrial uses. It is not used for drinking.

The Millenium Drought (2001–09) prompted investment in recycled, but it remains a small contributor to water supply, less than 10% across NSW. Recycled water production has not changed significantly since 2017–18 ().

Sydney Water’s recycled water schemes produced 40GL of recycled water in 2022–23 (). This provided additional water for irrigation and was used in place of drinking water. Demand for drinking water decreased by 12GL.

In the same period, Hunter Water supplied 3.2GL of recycled water to its customers and an additional 3.4GL to coNEXA, a third-party service provider. Supply of 6.8GL from recycled water saved about 5.8GL of drinking water ().

Desalinated water

Desalinated water is available in Greater Sydney. It plays a critical role as the region’s main rainfall-independent potable water supply increasing resilience to extreme weather events including droughts and floods.

Desalination uses advanced reverse osmosis technology to filter particles, salts and other pollutants from seawater. The treated water is integrated into the city’s water supply system.

See the Sydney Water website for more information on desalination.

Pressures and impacts

Impact on the environment

Changing water flows

Plants and animals are adapted to the natural variation in flows in rivers and streams (). Human-made changes to water flow can interfere with their lifecycles thereby harming these ecosystems.

Adverse weather and artificial barriers combined to cause mass fish deaths in the Darling–Baaka River in December 2018–19. Weather greatly reduced water inflow trapping fish between weirs, reduced oxygen in the water, and suffocating the fish (). Water infrastructure, such as the dams and weirs used for storage, irrigation, flood mitigation, and hydropower generation can both increase and decrease river flows (), alter the timing and seasonality of flows and modify water levels ().

These changes can destroy aquatic habitats, disrupt animal reproduction and lifecycles, and create physical barriers that prevent movement of species (; ).

Impact on water quality

The quality of environmental flows is important to the health of ecosystems. Healthy water has a natural range of temperature, acidity, oxygen content and other properties. It also has safe (typically low) levels of nutrients, metals and other elements.

See the Murray–Darling Basin Authority website for more information about healthy water quality.

Water quality can be degraded by runoff, industrial discharges and urban wastewater.

Stormwater runoff flows over urban infrastructure, such as roofs, driveways, streets, construction sites and industrial areas. It can carry leaves, dirt and other debris into receiving bodies, affecting their odour and colour. Stormwater runoff can also carry nutrients that can cause algal blooms ().

Agricultural runoff from fields and farmlands can introduce fertilisers, sediments and pesticides into receiving waters (; ).

Industrial discharges can contain heavy metals and synthetic chemicals ().

Urban wastewater, including untreated sewage, can significantly degrade water quality by increasing nutrient levels and introducing pathogens.

Water in rivers and storages are routinely tested by water utilities, local councils, and NSW government agencies to monitor water quality and aquatic ecology. See the NSW Government website for more information.

Many pollutants, such as nutrients and metals, are strictly monitored, and their potential impacts on the environment are well documented. However, previously un-monitored contaminants are always newly emerging ().

Water market

In NSW, Water Sharing Plans allow licensees to trade their water allocations under certain rules and regulations (). This trading system creates a water market that influences water use.

Through the water market, water can be reallocated to where it is most needed. Water rights can be temporarily or permanently traded from areas with surplus water to those facing shortages. This system helps increase supply during times of need and facilitates the return of water to the environment ().

Water trading has helped farmers to adapt to fluctuating water availability due to climate variability and droughts ().

While this system supports more efficient water distribution, it also adds complexity to water management (). Careful oversight is needed to make sure water trading is equitable and sustainable ().

Impact of water shortage on people and industries

Water security is an important concern in NSW.

In urban areas, the risk of water shortage can trigger tighter water restrictions. While these restrictions are necessary for water security, they affect the daily lives of people and the operation of businesses.

In regional NSW, water security strongly affects industrial productivity. Water shortage reduces crop yield and livestock production (). It also disrupts mining activities. Impacts on industry have flow-on effects, such as economic stress.

Achieving water security in regional areas is challenging, because a water source may be used by several water utilities ().

Population

Population growth is associated with urban expansion and increase in demand for food and other goods. This increases total water demand by households and industries.

See the topic for more information.

In urban NSW, water demand per capita has been stable over the past two decades because of increased water conservation and efficiency. (See the Urban water section of this topic for more information). Nonetheless, populations in places such as Greater Sydney are expected to grow and increase water demand to levels that surpass the available supply. Current water strategies and planning are focused on solutions to the supply–demand gap ().

In regional NSW, water demand is influenced by water-dependent industries, notably agriculture, food processing and mining. These industries contribute greatly to the NSW economy. They are anticipated to grow and increase water demand ().

Climate variability

Australia is a hot and dry country, and drought is a fundamental part of its climate and landscape.

Rainfall in NSW is highly variable owing to several climate drivers, notably the El Niño Southern Oscillation and the Indian Ocean Dipole ().

Major droughts that last up to several years, over wide areas, occur naturally. Seven have affected NSW since 1895 (; ).

Short-term and more localised droughts can also occur (). They too can have significant impacts, particularly if they occur while crops are growing.

Rainfall variability and droughts put significant pressure on water availability. When rainfall is lower, less surface water is available and water demand increases as agriculture and households increase irrigation. This poses a high risk of water shortage if storage is not large enough to cover dry periods.

See the and topics for more information.

Climate change

Changes in global and regional climate patterns are already affecting water availability and quality for communities and the environment of NSW.

Climate model projections show that our climate will be hotter with greater rainfall variability. We need to plan for more severe droughts and more flooding, particularly flash flooding from intense rainfall events. Moreover, the frequency and intensity of droughts is predicted to increase in some parts of NSW.

These climate changes will exert significant pressure on water management in NSW. We need to plan our approach to managing water to make sure water continues to be available to communities, industry and the environment. Both floods and droughts harm water quality and availability. Water management will need to consider water sources, including reducing reliance on rainfall, how much we need to store, and ways to minimise use including re-using water and reducing water losses in the water supply system.

Hotter, drier weather will also increase water usage as water is used to keep us cool. Good water management is crucial to making sure our communities remain resilient to climate change.

This is particularly evident in regional communities, which at times lacked suitable water during the 2017–20 drought.

In contrast, NSW faced several major flood events between 2020 and 2024. In 2022, it experienced the wettest spring on record, and many dams filled beyond capacity. Sequential rain events during this prolonged period created unprecedented flows into rivers and dams operated by WaterNSW. This can have significant, ongoing impact on the surrounding communities.

See the and topics for more information.

Responses

The way that industries and households use water, from extracting water from regulated rivers to discharging wastewater into waterways, affects aquatic environments and ecosystems. Plans and projects have been developed to reduce impact on the environment. These include better managing catchments and river flows, enhancing water quality monitoring programs and rehabilitating natural environments.

Water use in NSW is influenced by rainfall and drought. To increase resilience of water sources, various projects and initiatives were designed to enhance water efficiency and conservation. Additionally, water strategies were developed to address current and future water demand.

Reducing environmental impacts

Hunter catchment

Hunter Water has developed a Environmental Management Plan 2021–2024 that includes an objective to reduce impact on waterways. The plan aims to reduce wastewater overflows to the environment, develop catchment management strategies, and set up monitoring programs for emerging contaminants for wastewater and water resources.

Seaham Weir Refurbishment and Modification Project

Hunter Water upgraded the five-decade-old Seaham Weir on the Williams River to improve safety, enable effective management of water flow, maintain the weir pool’s water levels and improve fish passage. It installed four new low-flow gates on the eastern side of the weir to allow smaller releases of water when needed and provide a new fishway for improved fish passage both upstream and downstream. Works were completed in 2023.

Sydney catchment

One of the priorities of the Greater Sydney Water Strategy, released in August 2022, is to ensure waterways are healthy, including in the declared catchment area. An independent audit of the catchment is conducted every three years.

The latest audit () stated that recent climate-driven events – severe drought, bushfires and subsequent heavy rainfall events – have harmed catchment health. It also reported that actions taken by water management agencies in partnership with industry and the community have reduced many hazards to catchment health. These actions include restoration and rehabilitation of the natural environment and policy and decision-making backed by sound evidence.

The audit also noted the positive impact of the joint work of WaterNSW and NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service to control weeds and erosion. Disturbance in Special Areas has been minimised by restricting physical access.

Water security and resilience

Addressing water security risks across the state is critical to making sure suitable water is available. The NSW Government is working with local water utilities in the Town Water Risk Reduction Program. The program is developing long-term solutions to manage risks to water and sewerage services. It identifies barriers to strategic management and supports local water utilities to use their local expertise overcome them.

The first phase of the program, which concluded in July 2022, included various activities to help local water utilities to better manage risks and priorities. The second phase of the program, which will run until June 2025, aims to address critical skills shortages, develop collaboration with NSW Healths, and help local water utilities improve dam safety and reduce water quality risks.

The Safe and Secure Water program is a regional infrastructure co-funding program for eligible water and sewerage projects in regional NSW. More than $1 billion has been allocated to it.

Greater Sydney Water Strategy

Priority 2 of the Greater Sydney Water Strategy focuses on the security and resilience of Greater Sydney’s water supply. Key actions include a concentrated focus on water conservation and efficiency, optimising the use of Sydney Desalination Plant, planning for new rainfall independent water supplies and preparing for drought.

Greater Sydney Drought Response Plan

The Greater Sydney Drought Response Plan sets out how Sydney Water, WaterNSW and the NSW Government will work together to respond to droughts in the future. It is an adaptive plan that allows decisions and actions to adjust to observed conditions, growth and supply.

Lower Hunter Water Security Plan

The 2022 Lower Hunter Water Security Plan was prepared by Hunter Water and published by the NSW Government. It is a whole-of-government approach to ensuring the region has a resilient and sustainable water future.

The plan prioritises actions to improve water security including reducing drinking water use, strategies to increase water supply and implementation of rainfall-independent drinking water supply (a seawater desalination plant at Belmont). The plan also identifies how and when each action should be implemented to ensure Hunter Water and the NSW Government are accountable for each action.

Funding for local water utilities

About 90 local water utilities provide water and sewerage services to nearly 2 million people in regional and remote NSW communities. About 20% of these utilities have been assessed as at risk of water quality issues due to inadequate existing infrastructure. These utilities provide water to almost 600,000 people. The poor infrastructure increases their risk of water-borne diseases ().

Because some of these utilities serve small populations, local funding through council rates may not be enough to pay for maintenance. The NSW Productivity Commission reviewed alternative funding options to reduce risk for local water utilities in regional NSW. It noted the significant challenges and recommended ongoing well-targeted funding to support efficient water and sewerage operations that meet community expectations and statutory requirements ().

Water conservation

Water conservation reduces water demand and builds community resilience in preparation for and during times of water shortage.

Water utilities and councils lead conservation efforts (). Saving water outside of drought conditions encourages people to develop water efficient behaviours, preparing them for droughts and helps bolster reservoirs ().

Water restrictions can vary from place to place (). They limit or ban the use of water for certain purposes, such as watering, irrigation, cleaning and filling pools. They may also require leaks to be promptly fixed.

Strategies in NSW focus on further water conservation efforts to improve water efficiency and reduce water loss.

See the NSW Government website for more information about local water restrictions.

Water efficiency

Water efficiency measures can reduce water demand and increase water security.

Support for water efficiency projects

The NSW Water Efficiency Framework, first published in August 2022, has been designed for government, water utilities, councils and large businesses to use in planning, implementing and reviewing water efficiency programs. It provides detailed steps on how to meet water efficiency objectives and continue to make improvements.

Identifying options is a key step in developing a water efficiency plan. The Water Efficiency Opportunities Scan, released in 2020, helps to identify a broad range of water efficiency options and provides best practice examples. Examples include using water-efficient devices in showers, toilets and washing machines, automating control of irrigation, and providing rebates and grants for water-efficient appliances.

Fixing leaks

Leaks in water networks or in homes wastewater. Fixing leaks improves water efficiency and reduces water bills.

The Regional Leakage Reduction program, which began in March 2023, aims to help water local utilities to better identify and fix leaks. Grants have been awarded for investments in leak detection devices and building capacity in leakage control and metering. Since 2022, 9,950 million litres per year of network leaks have been found.

Planning for the future

NSW water strategies focus on ensuring the sustainable management and use of water resources to meet current and future demands. They include measures to improve water security, enhance water quality, and protect ecosystems while promoting efficient water use and resilience against climate change.

NSW Water Strategy

The NSW Water Strategy, first published in 2021, is a 20-year plan aimed at improving the security, reliability, quality and resilience of water resources across the State. It sets out strategic priorities and actions to address challenges such as climate variability and population growth. It includes 12 regional and two metropolitan water strategies specific to each area. By focusing on sustainable water management, it aims to ensure thriving communities and ecosystems for future generations.

NSW Aboriginal Water Strategy

The NSW Government is currently consulting Aboriginal communities on the development of an Aboriginal Water Strategy that will recognise cultural values of water and Aboriginal people’s water rights, and increase access to and ownership of water for cultural and economic purposes. A draft of the strategy became available for public consultation in August 2024.

Connectivity Expert Panel

A panel of independent experts was convened in 2023 by the NSW Minister for Water to provide advice on how to improve connectivity in the Northern Basin (Barwon–Darling) through improvements to rules in Water Sharing Plans. The panel’s recommendations, published in July 2024, propose multiple changes, including adopting a holistic approach to connectivity, recognising the importance of riparian targets and changes to rules in water sharing plans. The NSW Government is considering its response.

Future opportunities

The NSW Water Strategy and the two metropolitan and twelve regional water strategies identify strategic priorities to improve the management and resilience of NSW water sources.

The following opportunities could be explored to better protect water resources and manage water use:

- Water-sensitive urban design: This design principle integrates the water cycle with urban planning. An example is the use of nature-based solutions, such as raingardens or wetlands, to manage stormwater. These natural treatment processes slow down flows and remove pollutants from stormwater runoff, protecting water bodies (). Additional benefits include helping cities become greener, cooler and more liveable (). So far only small water-sensitive design projects have been implemented in Australia. Stronger policy and direction are needed ().

- Water efficiency: Further work is needed to enhance water efficiency. A potential focus could be the use of new sensor and digital technologies to detect leaks, maximise water savings and collect data to be used to develop water efficient strategies for households and businesses. Further research is needed to integrate them into practicable solutions ().

- Water quality monitoring and data management: A wealth of water quality data is collected by several agencies and industries across NSW. However, it is not clear what types of data are available and how reliable they are. There are also challenges in data collection, storage and sharing. The NSW Government’s NSW Water Quality Governance Roadmap, released in June 2024, identifies opportunities to improve the management of water quality information. It recommends aligning monitoring programs to fill data gaps and improve how data are stored, acquired, shared and interpreted. These actions will help inform policy decisions, operational responses and investment decisions ().

- Renewing or upgrading ageing water infrastructure: In Greater Sydney, ageing assets are close to capacity and are at risk of not meeting the needs of the growing population. Significant investment is needed to replace or upgrade them to meet water quality and environmental standards and to manage climate-related risks ().

Resilience can be enhanced by diversifying water sources, thus reducing reliance on rainfall. This approach will increase flexibility in addressing supply challenges due to droughts, floods and climate change.

Several opportunities are available:

- Increasing community awareness of purified recycled water for drinking: Stormwater or wastewater that has been treated to meet drinking water standards. Many cities around the world use purified recycled water, including Perth, where it is used to augment groundwater (; ).

Although purified recycled water is safe for drinking, gaining community support is a challenge (). Sydney Water opened a demonstration plant in Quakers Hill, Sydney in 2023 to increase awareness of the importance of rainfall-independent water sources to support population growth ().

Further work is needed to engage openly with communities, deepen their knowledge and build trust in water utilities and providers. - Recycled water for agriculture: Although the non-potable use of recycled wastewater in NSW is increasing, there is potential for further expansion. In its 2024 report on wastewater reuse opportunities, the National Water Grid identified areas in NSW that can supply treated wastewater for agriculture ().

- Reducing cost of seawater desalination: Seawater desalination is a proven rainfall-independent water source. However, its reliance on large amounts of energy makes the cost of the produce expensive. Further innovation to increase the efficiency of the process, and therefore increase the production of drinking water from seawater, may reduce the costs and energy use ().

- Research on brackish and saline groundwater desalination: There is also opportunity to use desalinated brackish and saline groundwater in agriculture. Further research is required to understand the needs of farmers and to reduce the cost through integration with renewable energy sources. Inland, there is a need to understand how to manage the brine (the concentrated liquid by-product of desalination) ().

References

WSAA 2013, Dams Information Pack, Water Services Association of Australia, Sydney

Image source and description

Topic image:Nari Nari Country–Murrumbidgee River, Hay Weir. Photo credit: Martin Asmus/DPI (2020).Banner image:Topic image sits above Butjin Wanggal Dilly Bag Dance by Worimi artist Gerard Black. It uses symbolism to display an interconnected web and represents the interconnectedness between people and the environment.

Image source and description

Topic image:Nari Nari Country–Murrumbidgee River, Hay Weir. Photo credit: Martin Asmus/DPI (2020).Banner image:Topic image sits above Butjin Wanggal Dilly Bag Dance by Worimi artist Gerard Black. It uses symbolism to display an interconnected web and represents the interconnectedness between people and the environment.