Global reporting models

Why report on the state of the environment?

The natural environment is essential to our daily lives in many ways – it provides the air we breathe, the water we drink and the soil that sustains our land and agriculture.

Reporting on the long-term condition of our environment helps us assess the effectiveness of actions we have taken to prevent, mitigate or fix damage to the environment and improve our care of it.

Aboriginal peoples have been observing and responding to changes in the environment since deep time, with observations tied to ongoing connections to and care of land, waters and all living beings.

Our reporting framework

The Pressure-State-Response framework for environmental reporting was developed and standardised in the latter half of the 20th century.

This model is often expanded or adapted – as it is in this report – to include impacts and other flow-on problems caused by environmental pressures and damage.

This expanded model is called Pressure-State-Response + Impact.

For example, a pressure such as the number of cars on public roads can affect the state of air quality (by increasing pollution) which leads to defined impacts on human health, such as an increase in respiratory illness in the population.

Responses include government policies, initiatives and strategies to help improve environmental condition and address pressures and impacts.

This model is used in NSW State of the Environment reports under the following headings:

- Status and trends (state) – the condition of the environment and trends in its condition over time

- Pressures and impacts (pressure) – what is causing the environmental problems and what this means for human and environmental health

- Response – what is being done, or can be done, to address the problems identified under Pressure and Status.

Reporting in this way can help to link the cause-and-effect relationship between environmental pressures and environmental performance, and between our actions and their impacts.

This helps us understand why protecting the environment is important for everyone.

In Australia, State of the Environment reports at Commonwealth, State and jurisdiction levels have only recently started to include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander values, perspectives and knowledges.

The NSW State of the Environment 2021 was the first time that NSW invited Aboriginal peoples to provide advice on the health of Country. Aboriginal voices will be an ongoing feature of NSW State of the Environment reports.

Thinking big for a better future

State of the Environment reporting and the Pressure-State-Response model have been useful for measuring and monitoring environmental changes and helping inform decision-making for governments and communities around the world.

However, other emerging approaches are also helping us understand relationships between the environment and human health and wellbeing.

At a time when we face climate and biodiversity crises, a burgeoning waste problem and increasing concerns about health impacts from exposure to pollution on land and in air and water, these approaches offer alternative perspectives on how to measure, report and manage our environment and actions in ways that balance environmental and human needs.

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs)

The United Nations 2030 Agenda for sustainable development, outlines how the world could eradicate poverty and help nations develop without continuing environmental harm.

The agenda sets out 17 Sustainable Development Goals that cover global issues such as climate action, clean water, responsible consumption and production, sustainable cities, gender equality and education.

The indicators in NSW State of the Environment 2024 have been mapped to these goals, targets and indicators to show how our reporting aligns with and supports sustainable development in NSW.

See the UN Sustainable Development Goals webpage for more information.

The Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF)

The Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which was adopted by the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 2022, sets out a global vision for the protection and more sustainable use of nature.

The Framework has four goals for 2050 and 23 targets for 2030 that align with the Sustainable Development Goals.

The 2030 targets include:

- conserving 30% of land, waters and seas (known as the 30x30 target)

- restoring 30% of degraded areas

- enhancing biodiversity and sustainability in agriculture, aquaculture, fisheries, and forestry

- enabling sustainable consumption choices to reduce waste and over-use of resources

- ensuring equitable participation in decision-making that includes Indigenous peoples.

As a party to the CBD, Australia is required to have a national biodiversity strategy and action plan that outlines how it will contribute to the GBF. The Australian Government’s Strategy for Nature 2024–2030 commits to a suite of nationally agreed biodiversity targets that support the GBF targets.

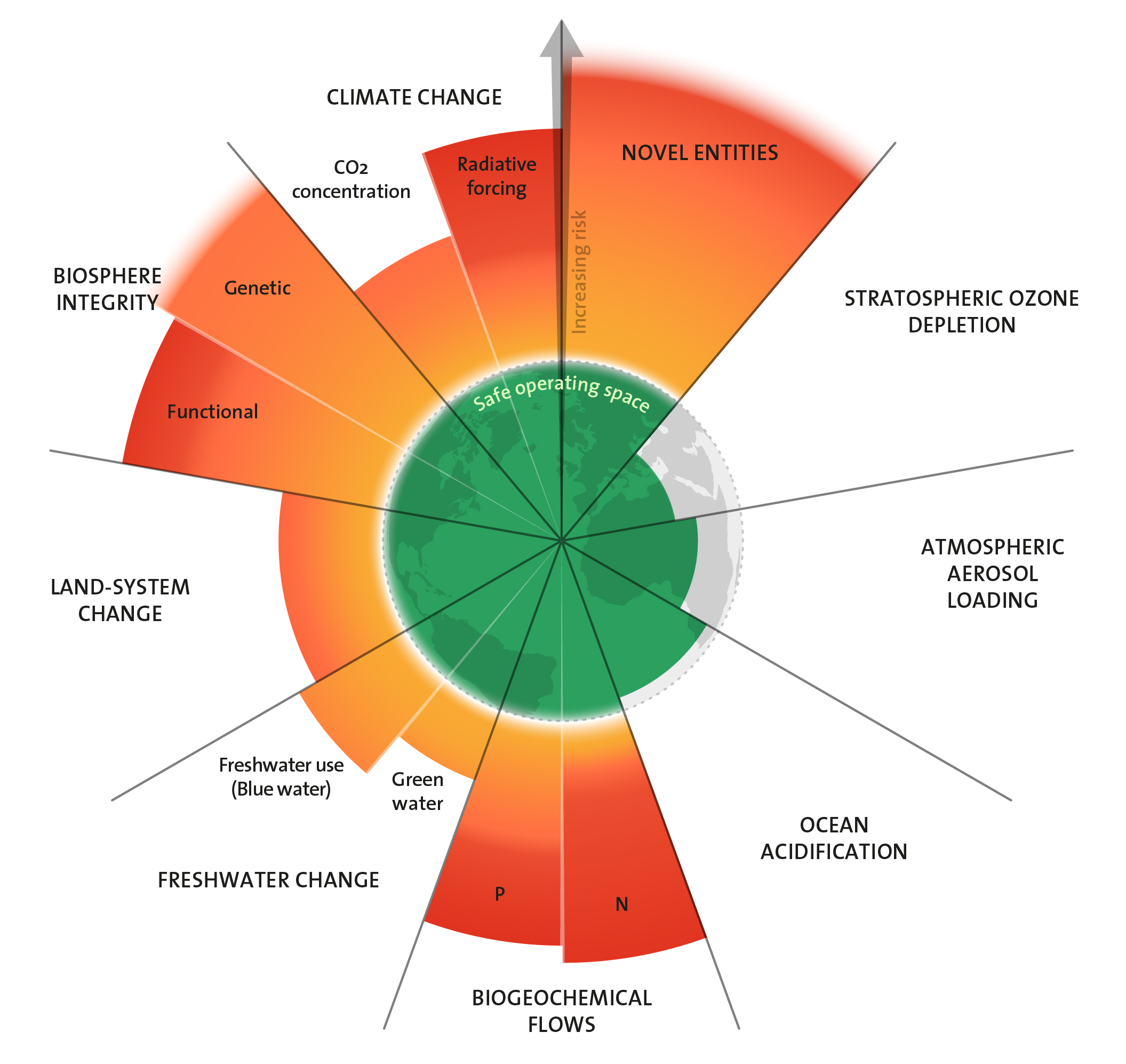

Planetary boundaries

The benefits of our environment are not infinite. Should human activities place extreme pressure on the earth’s systems and processes, this will cause catastrophic and enduring damage, such as irreversible climate change, unbreathable air and loss of food and water.

The planetary boundaries model was developed to help identify the environmental limits within which we can live safely on earth. It proposes boundaries for nine essential Earth systems (see Figure GR1.1).

The figure shows that if we go beyond the boundary of the green (‘safe’) zone, we enter an orange zone of ‘uncertainty’.

At this point, it becomes urgent to reverse the trend, because the next boundary, where orange changes to red, represents a danger zone where catastrophic and irreversible changes are much more likely to occur, threatening life on earth.

Since the concept was first developed in 2009, scientists have been ‘quantifying’ each of the boundaries – that is, deciding how to define or measure where they should be set – and investigating which boundaries have been crossed.

As Figure GR1.1 shows, all nine boundaries have been identified and six of them have now been crossed – in several cases entering the red danger zone.

While the original research was globally focused, since 2009 it has been explored at a smaller scale. For example, the European Union, The Netherlands () and New Zealand have all ‘downscaled’ the model to identify what the boundaries should be for their jurisdictions and assess whether any have been crossed.

A privately commissioned report, Living Within Limits (), has assessed five of the planetary boundaries in the Australian context. The researchers found that at the national scale, the boundaries for land system change, biodiversity integrity and biogeochemical flows have been transgressed and climate change and freshwater use are in the orange zone of uncertainty.

Planetary boundaries have not so far been used in any jurisdiction for State of the Environment reporting.

State of the Environment reporting in NSW uses a range of standards that have been established at global or national scales, such as the proposed limits for greenhouse gas emissions at the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. The standards used often measure thresholds for impacts on human health rather than environmental integrity, such as air quality standards and safe drinking water guidelines. See, for example, the and topics.

Environmental footprint

The environmental footprint approach compares how much humans use and consume resources with nature’s capacity to meet these demands.

The most well-known example, Earth Overshoot Day estimates the date each year humans are expected to exceed our global environmental budget and how many Earths would be needed after that point to meet our demands.

This is also called ‘ecological overshoot’.

When first estimated in 1971, the date was in December. By 2024, it has moved up to 1 August. This means we are using our environmental budget much faster than in previous years.

Earth Overshoot Day can also be explored at country-level.

Research by the Global Footprint Network shows that richer countries place comparatively more pressure on natural resources, suggesting they have greater responsibility to both prevent environmental damage and to help poorer countries develop without causing harm.

The footprint calculator enables this analysis at an individual level and can help identify ways to reduce your environmental impacts and tread more lightly on the earth.

The NSW SoE does not calculate an overall ecological footprint but discusses resource use per capita in the , and topics.

The ACT State of the Environment found that the territory’s ecological footprint was estimated to be over nine times the size of the ACT land area in 2023, meaning its current resource use was unsustainable.

The report noted that the ecological footprint had been decreasing over time, particularly with the growth in renewable electricity, but not fast enough to be at sustainable levels.

Environmental approaches in economic reporting

Economics provides a framework for how society manages its limited resources.

Up until the early 21st century, consideration of the environment has mostly not been integrated into mainstream economic thinking (). However, this is changing as societies and governments around the world increasingly recognise that the environment must be included in economic theory and policy so that the benefits it gives us can be protected.

The topic in this report outlines how new ways of thinking, such as natural capital accounting, are starting to be implemented in Australia and NSW.

These new economic approaches can also help government better align policies across different departments to ensure a consistent approach to environment protection and restoration across the state.

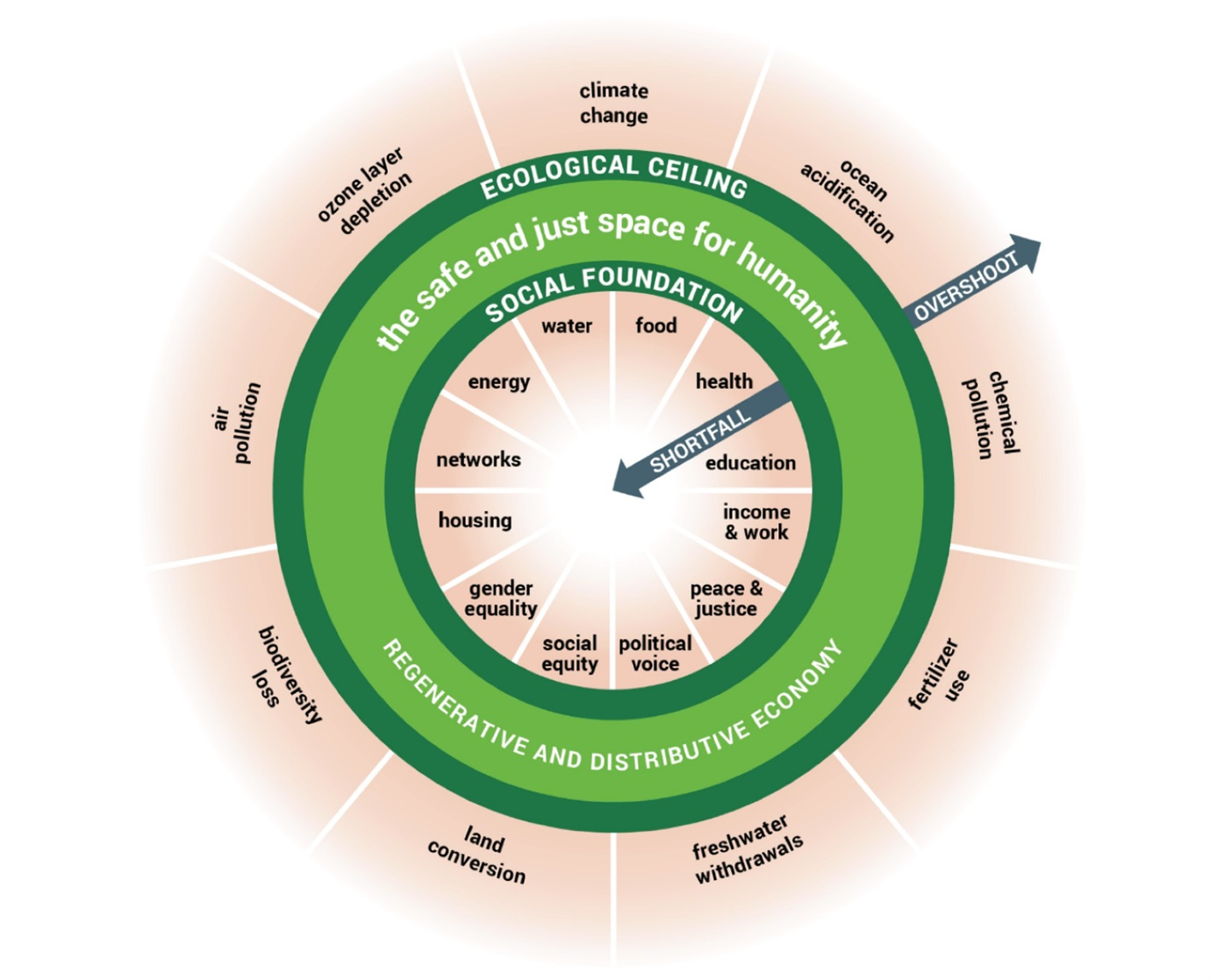

Doughnut economics

The doughnut economics model combines the planetary boundaries concept with sustainable development goals for economic and social justice to show how the worst-case and best-case scenarios interact (see Figure GR1.2).

The model recognises that everyone on the planet should have the resources to ensure they have a safe and comfortable standard of living.

The model includes:

- The ecological ceiling (planetary boundaries): these are the red, white and grey segments of the outermost circle, representing the upper limits on our use of resources.

- A social foundation (based on sustainable development goals): these are the red, white and grey segments of the innermost circle which set the minimum level of resource use to achieve economic and social justice goals.

- The safest place for humanity to thrive: Is between the ecological ceiling and the social foundation, which is in the doughnut-shaped green zone.

Figure GR1.2: Doughnut Economics model

This theory has been further developed and explored since it was proposed in 2012. For example, Amsterdam has downscaled it to city level and a community network in Sydney is exploring how the approach can inspire community-based projects such as urban farming.

Where to from here?

With humanity facing significant environmental threats in the 21st century, it is more important than ever to work out how we can be better environmental stewards for the beautiful planet we depend on.

Aboriginal peoples have cared for Country for tens of thousands of years. It is critically important that we listen to Aboriginal knowledges and wisdom from knowledge holders who can speak for Country to heal the environment, restore culture and care for communities through locally relevant and sustainable solutions.

Placing NSW in the global context will help individuals, communities, governments and businesses to develop solutions that also improve everyone’s quality of life and create a safer world for future generations to enjoy.

The NSW State of the Environment will continue to report using the Pressure-State-Response + Impact model because it aligns best with our legislative reporting requirements.

Further exploration of models like those above can further enhance our reporting.

We encourage you to also keep exploring what you can do as an individual and in your community to value and care for nature in NSW.