Topic report card

Read a one-page summary of the Economic activity and the environment topic (PDF 141KB).

Overview

All the elements have Lore, cultural Lore, right Lore.

Our trading practices included the exchange of cultural knowledge, various items and plant life. The seeds for trade would be wrapped up in a clay ball, which is how they're usually carried. So, you were carrying around five or seven clay balls, and inside those five or seven clay balls there could be anywhere between 10 to 15 to 50 different seeds in that ball.

If seeds were traded with other people, an explanation was given as to how and when to plant and water.

An economy is a complex system of human activities linking production, consumption and exchange of goods and services within a country or region.

According to the World Economic Forum, more than half the world’s economic output – about US$44 trillion – is moderately or highly dependent on nature.

Globally, construction, agriculture, and food and beverages are the largest highly nature-dependent industries. These industries could be significantly disrupted if ecosystem services are reduced or lost ().

There are many different frameworks that can be used to understand the complex relationship between the economy and the environment. It’s an understanding that continues to improve, as do solutions for alleviating pressures on the environment.

In this topic, the focus will be primarily on key features of the NSW economy and environmental impacts, although a global perspective is also considered.

Opportunities for using new economic frameworks to improve environmental outcomes, such as nature positive, sustainability disclosures and circular economy initiatives, will be discussed.

Table D2.1 defines some important economic terms that are used throughout this topic.

Table D2.1: Key economic terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Decoupling | Decoupling occurs when two or more activities grow at different rates, when in the past they may have grown at the same rate. |

| Gross state product | Gross state product is a measure of the value of all the goods and services produced in the state or territory in a given time period. It captures price and output volume changes. |

| Real gross state product | Real gross state product is a value measure of the volume of all goods and services produced. It removes the impact of price changes on the value of gross state product. |

| Gross value added | Gross value added is the value a sector or industry adds to the economy through its activity. Gross state product can be calculated by adding up the Gross value added for all sectors of the state economy. |

| Natural capital accounting | Describes the state of the natural environment and its links to the economy in a standardised way. Also known as environmental-economic accounting (). |

| Cost-benefit analysis | Cost-benefit analysis is a holistic appraisal method that estimates the economic, social, environmental and cultural costs and benefits of an initiative, and expresses them in monetary terms. |

| Ecosystem services | A set of assets (natural resources as well as entire ecosystems) that generate benefits on which humans rely, such as clean air and water. |

| Circular economy | The circular economy refers to a systems transformation from a linear economy (extraction, use, disposal) to the circularisation of material (manufacture, reuse, repair, recycling, re-manufacture). |

Relationship between economy and environment

Human wellbeing and the economy depend on nature as a:

- source of resources to be converted into products

- sink for waste products

- supplier of critical ecosystem services, such as carbon sequestration or water filtration services.

Population growth and rising standards of living lead to economic growth, and in turn, economic activity leads to pressures on the environment.

Population growth is one driver of economic growth in industrial economies due to the increased need for essentials, such as food and housing, as well as other goods and services. The resulting economic growth is often related to increased consumption, resource use and the generation of waste and pollution ().

See the and topics for more information.

Economic growth is the increase in the production of goods and services over time. If economic growth is greater than population growth, this increase enables people to improve their living standards and lead safer and more comfortable lives.

In turn, this increased economic activity can lead to pressures on the environment, as the way we produce goods and services can have substantial negative impacts on the environment and human health.

The relationship between economic growth and the environment is complex, with different sectors of an economy having different levels and types of environmental impacts.

Environmental impacts depend on the nature of the economic activity, the changing structure of industry, and the policy settings and regulatory framework in which that economic activity takes place.

Environmental impacts within a state, such as NSW, also depend on whether an economy uses domestic or imported resources and whether the goods and services produced are consumed locally or exported.

Because economies are linked globally, the environmental impacts of a state economy may include impacts on the environment in that state, as well as other parts of the country or overseas.

Economic growth can be responsible for generating more pollution as people consume more goods and services (). However, economic growth often improves environmental outcomes, as richer countries can afford to devote more of their resources to environmental regulation and to nature protection and improvement (). For example, policies to reduce carbon emissions can provide new opportunities for farmers to generate renewable energy alongside other land uses.

Slowdowns in economic growth don’t necessarily lead to better results for the environment. Brief reductions in economic activity can lead to improved environmental outcomes – for example, NSW recorded a reduction in the number of littered items during the COVID-19 emergency, only to return to baseline levels afterwards ().

However, extended recessions can also cause extra damage or degradation as business enterprises struggle to maintain viability. This may result in pressure for short-term exploitation of available natural resources or less care and attention paid to the generation and management of waste.

Natural capital

The concept of nature as an asset that provides benefits to humanity is becoming more important in economic policy and strategy (; ). This means valuing nature explicitly for its economic benefits and ensuring our environment is managed so that it can continue to benefit future generations.

Natural capital refers to the framing of nature as an asset that generates value.

One tool to implement this way of thinking is known as natural capital, or environmental-economic accounting, which is a technique to measure how the amount, quality and uses of natural capital change through time. It supplements conventional economic accounts and enhances government decision-making by enabling environmental factors to be considered in decisions that have traditionally been based on economic factors alone.

Other economic tools that are used by governments to prevent or mitigate environmental impacts include cost benefit analysis, taxes, offsets and market-based mechanisms, such as offsets and tradeable permits.

Related topics: | | | | |

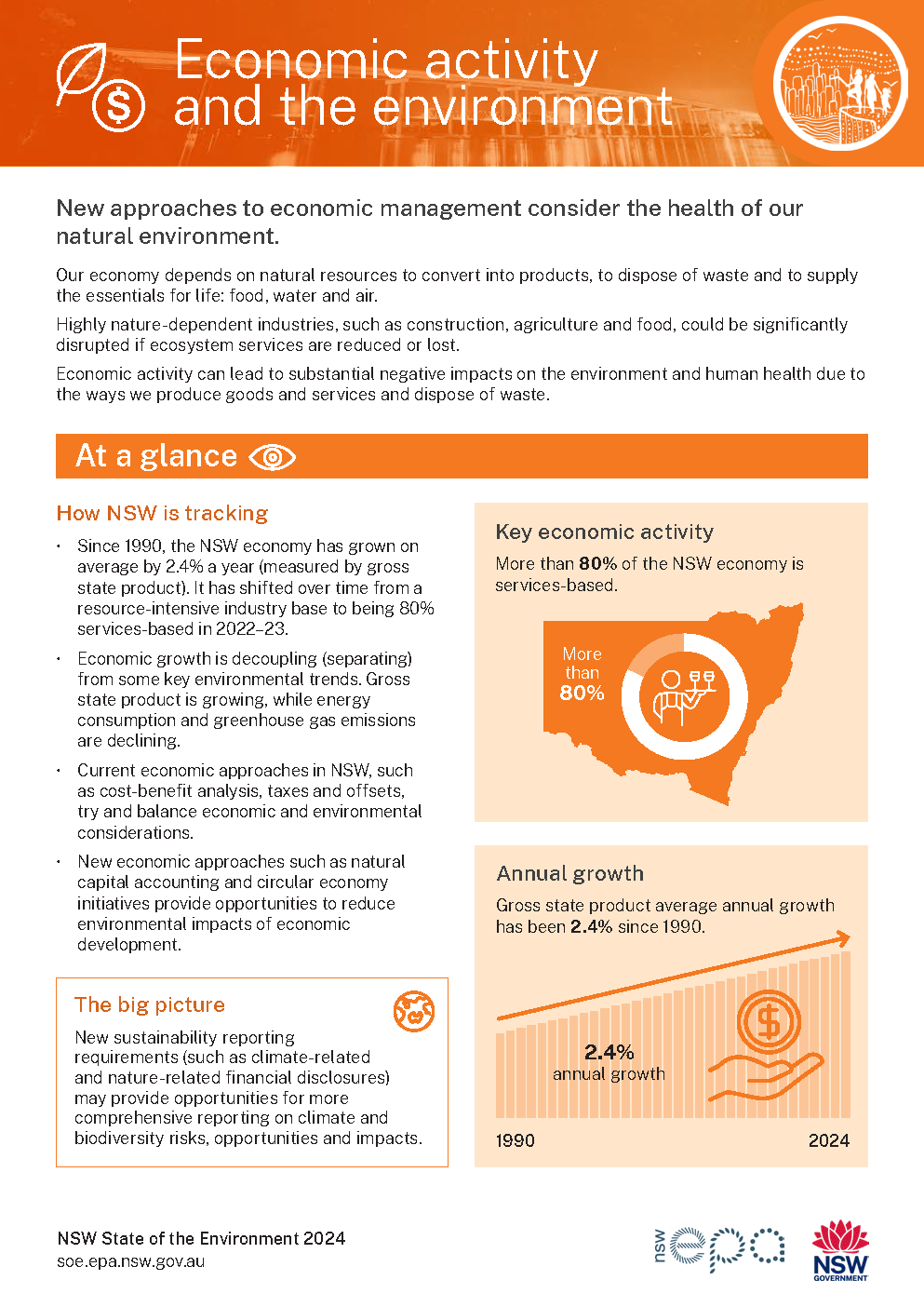

The NSW economy

NSW has the largest economy in Australia, contributing about one-third of national economic output in 2023. Between 1990–91 and 2022–23, NSW economic output doubled as the NSW economy grew by an average 2.4% a year, as measured by gross state product (see Figure D2.1).

Figure D2.1: Economic growth (annual percentage change in real gross state product), 1990–91 to 2022–23

As a result of this sustained economic growth, NSW gross state product per person increased by about $32,136 in real terms between 1990–91 and 2019–23, reaching $89,314 in 2023 (). This means the share of state wealth per person has increased and people would, on average, have higher living standards now compared with 1990–91.

Over the past 30 years, the NSW economy has been shifting from resource-intensive industries, such as manufacturing, mining and agricultural production, to the services and technological sectors. These sectors are less dependent on the use of natural resources, and typically involve lower environmental impacts than primary and secondary industries, such as farming, mining and manufacturing.

Figure D2.2 shows that NSW is now primarily a service-based economy, with services contributing more than 80% of gross state product in 2022–23 ().

Figure D2.2: Sectors of the NSW economy (share of gross state product), 2022–23

Notes:

Each sector’s share is shown in nominal dollar values, which capture changes in prices as well as volumes produced.

‘Other services’ includes sectors such as public administration, media and information technology, rental and hire services, retail and utilities, such as water and gas.

While manufacturing remains a major sector in the NSW economy, its share of the economy has fallen from 12.5% of gross value added () in 1990 to 5.3% in 2023.

Over the same period, the financial and insurance services sector share of the economy grew from 6% to 9.2%, overtaking manufacturing as the State's largest sector in 2005, and the information, media and telecommunications sector grew the fastest, with real annual average growth of 5.35%.

While the share of services sectors increased over the period from 1990–91 to 2022–23, growth in resource-intensive industries continues. Average annual growth was 11.6% for mining, 2.5% for manufacturing, and 4.6% for agriculture, forestry and fishing ().

Economic growth and environmental impacts in NSW

There is evidence that there has been a reduction in some environmental impacts while the NSW economy has been growing. A doubling in the size of the NSW economy (measured as gross state product) and a 40% increase in population over the past 30 years have not generated proportionate increases in energy consumption and carbon emissions.

During this period, as shown in Figure D2.3:

- Gross state product average annual growth was 2.4%, a total increase of 118%

- the NSW population grew by an annual average of 1.0% a year, a total increase of 41%

- net carbon emissions fell by an annual average of 1%, a total fall of 31% (from 169,166 kilo tonnes to 110,997 kilo tonnes)

- total energy consumption annual average growth was 0.6%, a total increase of 20.7%.

Figure D2.3: Relative change (%) in economic performance, population, energy consumption and carbon emissions in NSW, 1989–90 to 2022–23

Total carbon emissions have been declining since 2007, and energy consumption, while growing over the period, started to decline in 2011. These trends are likely due to:

- adoption of more energy efficient technologies

- industries transitioning towards low-emissions, renewable energy sources to generate electricity

- changes to government policy, including greenhouse gas emissions regulation and sustainability disclosure requirements

- greater consumer engagement and attention to energy use and cost, including increasing the amount of generation for own use.

See the topic in this report for more information.

A deeper analysis of economic growth, carbon emissions and energy use shows a fall over time in the intensity of carbon emissions and energy consumption in the NSW economy (see Figure D2.4). This means the emissions produced and the energy used for each dollar of gross state product are falling while the economy continues to grow.

- Carbon emissions in tonnes per dollar of gross state product fell by 63% from 1990 levels.

- Energy intensity fell to a lesser extent, to about 46% of 1990 levels.

See the , and topics in this report for more information on emissions and energy use by sector.

Figure D2.4: Relative change (%) in NSW economic performance, emissions and energy intensity 1990–1991 to 2021–2022

Notes:

Energy intensity is measured by energy consumption per unit of gross state product.

Current economic approaches in NSW

Cost-benefit analysis

Cost-benefit analysis is a method that estimates the economic, social, environmental and cultural costs and benefits of an initiative and expresses them in monetary terms. It can be used to assess whether the trade-offs between economic activity and particular environmental outcomes are appropriate.

Cost-benefit analysis is the NSW Government’s preferred economic evaluation method. It is required as part of a business case to support funding proposals.

Under the NSW Government Guide to Cost-Benefit Analysis (Treasury Policy and Guidelines 23-08), cost-benefit analyses are required for NSW Government policies and programs with an estimated cost of $10 million or more. These decisions can be complex, with many stakeholders and competing interests involved.

For example, while the community benefits from new roads, housing, infrastructure and other developments, these should be weighed up against the environmental assets, such as a threatened species, that are impacted when land is cleared.

Examples of environment-related benefits in cost-benefit analyses could include:

- reduced impacts from climate change resulting from greenhouse gas emissions reductions

- lower health costs from reduced air pollution and improved water quality

- improved natural sites that provide recreation benefits for hikers and campers.

Examples of environment-related losses may include:

- fragmentation and loss of habitat for vulnerable species of plants and animals

- increased air pollution

- impacts on water quality and supply.

The NSW Government’s NSW Climate Change Policy Framework commits to developing a benchmark value for emissions savings and applying this consistently in government economic appraisal. This means cost-benefit analysis for all new policies and programs will use the same value for benefits from emissions savings.

The Framework for Valuing Green Infrastructure and Public Spaces provides a standardised way to identify and quantify costs and benefits associated with green infrastructure and public space projects.

The NSW Treasury’s Centre for Economic Evidence collects data on conservation programs where cost-benefit analysis has been used to better understand how well this tool is working. This work will continue to contribute to insights about the potential environmental impacts of different types of development that can be incorporated in future analyses.

This data may also help the government estimate potential environmental impacts for projects where not enough information is available.

For example, ecosystem and species credits issued under the NSW Biodiversity Offsets Scheme are bought and sold, and the price for such credits can be used to indicate the value of the ecosystem or species concerned. These prices may be used to show the economic value of species conservation and of ecosystem preservation.

This cost-benefit analysis approach was used to quantify species conservation benefits in the NSW Saving Our Species program.

Economic incentives

Economic instruments and market-based mechanisms are policies, tools and programs that provide incentives for businesses and the community to consider the wider social impacts of their behaviour. They include taxes, subsidies, offsets, tradeable permits and similar financial incentives.

An aim of economic instruments is to allow economic growth and efficient allocation of resources. The main advantage of using economic instruments is that, by harnessing incentives to reduce costs, they can achieve desired environmental outcomes at lower costs than via alternative (usually regulatory) means.

A range of economic instruments designed and managed by the NSW Government use financial incentives to modify the choices and actions of businesses and residents of NSW in relation to environmental impacts.

These include:

- the waste levy, which provides financial incentives for residents and businesses to reduce the amount of waste they send to landfill

- solar feed-in tariffs, providing an incentive for investing in household solar generation capacity

- load-based licensing, which imposes a charge on industrial facilities for each tonne of pollution they emit, encouraging these businesses to incorporate the wider social costs from pollution into their production decisions

- risk-based licensing, which matches the degree of regulatory oversight with the level of environmental risk posed by licensed operations by targeting poor performers and creating a financial incentive for facilities to improve their systems and performance

- the financial incentives provided by the NSW Container Deposit Scheme Return and Earn, which encourages the return of used drink containers for recycling.

Environmental instruments and markets

Environmental markets aim to encourage people to take action to protect or restore the environment by investing in environmental goods and services. Participants can buy, sell or trade these goods or services for potential financial gain.

Environmental markets are new and evolving. As markets develop, continuous improvements and adjustments will be required to ensure they function effectively and efficiently.

Examples of environmental markets within NSW include:

- the Biodiversity Credits Market, which enables landholders to establish biodiversity stewardship sites to generate biodiversity credits that can be sold to development proponents to meet their offsetting obligations under the Biodiversity Offsets Scheme

- the Hunter River Salinity Trading Scheme, which allows industry participants to trade with each other for the right to discharge saline wastewater to manage pressure on the river’s ecosystem

- the NSW Energy Savings Scheme, which creates an incentive to reduce the consumption of electricity and gas by requiring electricity retailers and some large users to meet targets for energy savings certificates that are created on a voluntary basis by private sector service providers

- the Peak Demand Reduction Scheme, which sets a target for electricity retailers and large users to reduce energy demand during peak hours by creating or buy peak reduction certificates.

Some of the challenges associated with environmental markets are:

- Establishing effective scheme design and operation that minimise barriers to market entry and exit, minimise transaction costs on market participants, and minimise the administrative burden on the government responsible for managing the market (or scheme).

- Integrating economic instruments, including regulatory ones, into a larger system of environmental protection initiatives. When poorly implemented, it can limit their effectiveness ().

- Information issues where it is difficult and expensive for market participants to get trustworthy information on products and services. For example, in environmental markets there are risks of ‘greenwashing’. This is where environmental claims aren’t backed up by reliable evidence, making products, services or operations appear more sustainable than they really are (; ).

Biodiversity offsetting

The Biodiversity Offsets Scheme (established by the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016) provides for development impacts on biodiversity to be offset by gains secured through stewardship agreements.

The scheme requires proponents of activities that will have a significant impact on biodiversity to first avoid and minimise those impacts before offsetting any residual impact.

Landholders who enter into these stewardship agreements are required to set up biodiversity stewardship sites to conserve and restore habitat, with the aim of delivering ‘no net loss’ to biodiversity. A transparent, consistent and scientific method is used to calculate and unitise the loss and gain in biodiversity values.

See the and topics for more information about biodiversity.

Monitoring the NSW biodiversity credits market

The Biodiversity Offsets Scheme is an example of an economic instrument that has been the subject of public scrutiny.

The Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal (IPART) has been asked by the NSW Government to monitor the biodiversity credits market, for three years from 2022–23 and make findings and recommendations.

In December 2023, the first monitoring report found several challenges affecting fundamental aspects of the market such as pricing, transaction costs and barriers to entry. The report made recommendations to remove price distortions, and other actions to reduce entry costs and make the market more accessible for landholders and development proponents to trade credits.

IPART conducted its second annual review of the credits market in late 2024, released in December. The review is expected to consider trends in the performance of the market in 2023–24, including any NSW Government responses to the recommendations from the first report.

The Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, which establishes the NSW Biodiversity Offsets Scheme was reviewed in 2023. The NSW Plan for nature is the NSW Government’s response to the independent statutory reviews of the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 and the native vegetation provisions of the Local Land Services Act 2013. The NSW Government is implementing a range of reforms to strengthen and improve the offsets scheme, including legislative reform.

NSW DCCEEW also administers the Biodiversity Credits Supply Fund, to increase the supply of in-demand biodiversity credits and enhance confidence in the biodiversity credit market. Through the Stewardship Support Program, eligible landholders are supported to identify and access stewardship opportunities under the Biodiversity Offsets scheme.

Greenhouse gas offset schemes

Greenhouse gas offset schemes (including carbon offset schemes) are economic instruments that encourage people and businesses to carry out activities that reduce emissions or store carbon.

Offset schemes in Australia include:

- the Australian Carbon Credit Unit Scheme, which encourages people to reduce emissions by using new technology, upgrading equipment, changing business practices or changing the way vegetation is managed

- Safeguard Mechanism credit units, which are tradeable credits that businesses liable under the Safeguard Mechanism (the highest greenhouse gas emitting facilities in Australia) can earn by reducing greenhouse gas emissions beyond their baseline.

See the topic for more information.

Economic growth and net zero

Getting to net zero emissions is an important part of the NSW Government’s plan to grow a sustainable low carbon economy.

The Climate Change and Net Zero Future Act 2023 ensures that economic outcomes are a priority of NSW action on climate change through the Net Zero Plan. The Act notes among its guiding principles that action to address climate change should be taken in a way that:

- is fiscally responsible

- promotes sustainable economic growth

- considers the economic risks of delaying action to address climate change

- considers the impact on rural, regional and remote communities.

See the topic for more information.

Environmental limits to economic growth

Decoupling and its limitations

By definition, because the economy is critically reliant on environmental inputs, it is not possible to completely ‘decouple’ economic growth from the environment. However, separating or ‘decoupling’ economic growth from its potential negative environmental impacts is important in creating a sustainable future.

Decoupling can involve:

- reducing the amount of resources, such as fossil fuels, used to drive economic growth through more efficient practices to reduce their overall negative environmental impact ()

- using resources more efficiently or cleanly, without reducing the amount of resources used or the cost of production ().

In NSW, carbon emissions have been decreasing while the State is still experiencing economic growth, indicating some decoupling of carbon emissions from economic growth. See The NSW economy section of this topic for more information.

Although decoupling shows encouraging signs, decoupling alone will not be enough to achieve the scale of changes required to prevent irreversible environmental degradation (; ).

There are challenges for decoupling other aspects of the economy from environmental impacts, particularly in international trade, due to Australia being a large exporter of natural resources ().

Economic innovation and sustainable resource management strategies are still needed to support decoupling of economic growth from resource consumption and their negative environmental impacts ().

Living within environmental limits

The frameworks we use to understand the relationship between the economy and the environment have changed over time. These frameworks explore limits of the capacity of the global environment to support continuing, and increasing, economic activity.

The extent to which humanity is pushing up against planetary limits is a recurring economic question.

Up until the early 21st century, consideration of the environment had mostly not been integrated into mainstream economic thinking (). However, this is changing as societies and governments around the world increasingly recognise that nature must be included in economic theory and policy so that the benefits it gives us can be protected. An example is The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review, commissioned by UK Treasury in 2021.

See thepage for more information.

Table D2.2 outlines the development of various frameworks for addressing environmental limits. The evolution of frameworks reflects growing understanding of what drives economic growth, and the role innovation plays in decoupling growth from unwanted environmental impacts.

Earlier works tended to propose definite and time-bound forecasts of global crises or failures of economies caused by depleting natural resources and food supplies. While these predictions have not come to pass, it is important to consider the context in which these reports were published. The quality of economic forecasts has improved due to a better understanding of the links between nature and the economy.

More recent works have tried to define and diagnose problems and solutions based on a perception of planetary limits and the human systems operating within them. Significantly, what these recent economic reports have in common is a focus on the limits of the global environment to support continuing, and increasing, economic activity.

These more recent frameworks make recommendations for policy responses in the face of human society pushing up against these planetary limits.

These ways of thinking about the relationship between the environment and economic activity have influenced how governments respond to environmental issues.

New and emerging economic approaches can also help governments better align policies across different departments to ensure a consistent approach to environment protection and restoration across the state.

Table D2.2: Developments in consideration of nature in economics

| Work and year published | Summary |

|---|---|

| An Essay on the Principle of Population | Predicted that population growth would overwhelm economic gains in food production, based on the observation that the majority of the population usually lived at subsistence levels. The author, Robert Malthus, thought the result would be wars, famines and societal breakdown (). Malthus’ insight was valid for its time, but the great increases in production and living standards associated with the Industrial Revolution have since disproved Malthus’ predictions. It is worth noting that Malthus’ argument was based on repeated observations of the vast majority of the population living at subsistence levels for much of the time. |

| The Population Bomb () | Predicted worldwide famines due to overpopulation and advocated immediate action to limit population growth. This book updated a Malthusian-style prediction of economic and societal collapse resulting from overpopulation. Strict population control measures were advocated in the book. The book’s predictions have not come to pass. |

| The limits to growth (1972) | Examined development trends of population growth, industrialisation, malnutrition, exploitation of raw materials and destruction of the living environment. It contained forecasts of 'overshoot and collapse' based on exhaustion of supplies of critical resources. The report was widely criticised, including by economists, for ignoring technical change, resource substitution and the role of prices as allocative mechanisms. |

| Our Common Future (1987) | Also known as the Brundtland Report, this introduced the concept of sustainable development as ‘Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.’ Broadly consistent with asset-based natural capital view (discussed below): that current generations should pass on a sufficient (and diversified) portfolio of assets to enable future generations to thrive. |

| The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review (2006) | The review found that the benefits of strong and early action to limit climate change far outweigh the economic costs of not acting. |

| The Garnaut Climate Change Review (2008) | Garnaut’s report set targets for climate action and recommended an emissions trading scheme as the key policy mechanism to achieve the targets. |

| Planetary boundaries (2009) | The planetary boundaries concept was developed to help identify the environmental limits within which we can live safely on earth. It proposes boundaries for nine essential earth systems, based on what we take from the earth (such as water and land use) and the waste that is returned to the environment (such as greenhouse gases and aerosols). The Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research produces a yearly update to the framework, called the Planetary Health Check. The 2024 report showed that six of the nine boundaries have already been exceeded. |

| Doughnut economics (2012) | The doughnut economics model combines the planetary boundaries with the sustainable development goals for economic and social justice. The model aims to recognise that all people should have the resources to ensure they have a safe and comfortable standard of living, while not collectively overshooting the planetary boundaries. |

| The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review (2021) | The review calls for changes in how we think, act and measure economic success to protect and enhance our prosperity and the natural world. Grounded in a deep understanding of ecosystem processes and how they are affected by economic activity, the new framework presented by the review sets out how we should account for nature in economics and decision-making. |

Notes:

Links or references to works are included on each listing above.

New and emerging approaches

Nature as an asset

Globally, governments and businesses are beginning to examine nature as an asset that provides benefits to society and which should not be treated as a ‘free’ good. One way of measuring the relationship between the economy and the environment is known as natural capital accounting (see below for more detail).

This approach categorises nature as a set of assets – natural resources as well as entire ecosystems – that generate the benefits (known as ecosystem services) on which humans rely. An example is the provision of clean air and water.

This framing puts nature on par with other produced assets whose value is recorded in both company and national accounts. It repositions nature from being ‘outside’ regular human economic activity, to being something that underpins it ().

Using this approach, the UN World Economic Forum estimated that more than 50% of the world’s gross domestic product relied on nature ().

In 2022, the NSW Government released the NSW Natural Capital Statement of Intent (). The statement sets out a series of objectives, including:

- recognising the value of, and our impact and dependencies on natural capital, while mitigating risks against losses

- recognising the importance of land managers’ ability to support ecosystem services

- recognising Aboriginal peoples’ connection to Country and traditional land knowledges

- building on existing initiatives that integrate the enhancement of natural capital

- fostering an enabling environment that supports the economic transition towards a nature-positive economy.

The statement provides a pathway to guide and inform NSW Government decision-making, aiming to conserve and enhance the environment while ensuring economic prosperity.

The statement also supports several natural capital programs.

Natural capital accounting

Natural capital accounting is an umbrella term that describes accounting for the environment and its natural assets in a way that is similar to how we account for what happens in the economy. It refers to a systematic, standardised and repeatable framework in which information on natural capital and the resulting ecosystem services it provides are recorded, whether or not those services have a market value.

Natural capital accounting in Australia and NSW uses the internationally endorsed System of Environmental-Economic Accounting (SEEA) Central Framework, which was developed by the United Nations ().

SEEA uses a systems approach to linking environmental and economic information to describe the stocks and flows of natural resources. It does this by integrating environmental and economic data into a standard measurement system.

The framework expands the boundaries of the Australian System of National Accounts, the conventional method of recording and tracking changes in economic activity at national and state levels.

The standard national accounts focus on changes in economic activity, and do not include environmental pressures or environmental assets – ‘natural capital’ – which includes renewable and non-renewable resources, as well as entire ecosystems.

Data from environmental-economic accounts can be used to show links between economic activity and various aspects of natural resource use, including the generation of ‘residuals’, such as waste products and pollutants.

The data can also be used to explore trends in the use of natural resources and how these trends affect the extent and condition of remaining stocks and patterns of pollution and waste discharged to the environment. This helps decision-makers explore relationships between the economy and the environment.

Australian natural capital accounts

National environmental-economic accounts, including experimental accounts, have been developed to assist national-scale planning. Some accounts are called ‘experimental’ because this style of accounting is a relatively new and emerging field of measurement.

The national environmental-economic accounts that have been developed so far include:

- Energy Account, Australia 2022–23

- Energy Use and Electricity Generation, Australia (Businesses) 2017–18

- National Ecosystem Accounts 2021–22 – experimental estimates

- National Land Cover Account 2024

- National Land account 2021 – experimental estimates

- National Ocean Account 2022 – experimental estimates

- Waste Account, Australia 2018–19 – experimental estimates

- Water Account, Australia 2021–22.

More information is available at Natural Capital Accounts, and on an interactive dashboard for land and ocean accounts.

NSW natural capital accounts

NSW can use the national environmental-economic accounts to identify differences in resource use and impact between the states and jurisdictions.

In July 2024 NSW launched a Natural Capital Accounting Hub on SEED, the NSW Government’s environmental data portal. Experimental accounts for NSW published to date include:

- biodiversity accounts using data from the NSW Biodiversity Offsets Scheme and the prior Biobanking Scheme

- soil condition and land use accounts

- soil carbon accounts.

The NSW Government is also developing an experimental marine ecosystem account and several pilot accounts in the Hunter Functional Economic Region.

Biodiversity targets

Australia is a party to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), a global treaty for conserving biodiversity, the sustainable use of its components and the equitable sharing of benefits from using its genetic resources.

In 2022, the 15th Conference of the Parties to the Convention (COP15) adopted the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF).

Among the framework’s key elements are four goals for 2050 and 23 targets for 2030, including the 30 by 30 target whereby governments commit to designate 30% of earth's land and ocean area as protected areas by 2030.

As a party to the CBD, Australia is required to have a national biodiversity strategy and action plan that outlines how it will contribute to the GBF. The current plan, Australia’s Strategy for Nature 2024–2030, commits to a suite of nationally agreed biodiversity targets. The strategy recognises that the decline of Australia’s biodiversity is a source of systemic risk for the economy. It also recognises a need to develop options for measuring of natural capital and ecosystem services through national environmental-economic accounts ().

The Australian government is working with states and territories to deliver the plan. This will include efforts to incorporate biodiversity considerations into government and business decision-making in NSW ().

With natural capital accounts, used to measure progress against biodiversity targets and the ecosystem services provided as a result, it is possible to determine the economic impact of achieving targets.

See the , and topics for more information.

Transitioning to a circular economy

The NSW 2040 Economic Blueprint identified that one of the ‘megatrends’ shaping the State’s economic future over the next 20 years is the need to change the way we produce and consume goods and services to reduce our impact on the environment ().

NSW is transitioning to a circular economy over the next 20 years (). A circular economy is an economic system aimed at minimising waste and promoting the continual reuse of resources.

The circular economy aims to keep products, equipment and infrastructure in use for longer, thus improving the productivity of these resources. This regenerative approach contrasts with the traditional linear economy, which has a ‘take, make, dispose’ model of production. Examples of circular processes include:

- designing products that last longer and can be easily repaired

- using recycled materials in manufacturing

- repairing household goods before buying new ones

- ensuring the materials used in a product are still valuable for other purposes when consumers have finished using it.

The CSIRO reports that Australia’s circularity rate is close to 4%, which is half the global average of 8% ().

Circular economy initiatives underway in NSW and Australia include:

- reviewing the waste levy – exploring how adjustments to the operation of the waste levy could reinvigorate the incentive to recycle while minimising impacts on cost-of-living and making it easier for waste operators to do the right thing

- enhancing the NSW resource recovery framework – responding to recommendations contained within the Independent Review of the NSW Resource Recovery Framework to ensure regulatory settings and requirements are fit for purpose to enable circular economy in NSW

- expanding the Return and Earn scheme – accepting more types of beverage containers, including glass wine and spirit bottles and larger containers

- setting up new and expanded product stewardship schemes – these are key enablers of a circular economy approach because they provide incentives for businesses to design products with reduced environmental and social impacts, and encourage reuse and recycling. They can include financial or other incentives to avoid waste.

See the topic for more information.

Sustainable finance

Sustainable finance is the integration of environmental, social and governance (ESG) matters into economic and financial decision-making. Sustainable finance can be used as a tool to promote sustainable economic growth.

For example, the NSW Sustainability Bond Programme allows investors to finance a range of green and social projects, such as low carbon transport, sustainable water and wastewater management, affordable housing, affordable basic infrastructure and access to essential services.

Australia is party to the Paris Agreement. Part of the agreement includes working to make finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development ().

Read more about Australia’s international cooperation on climate finance projects.

See the for more information.

Australian sustainable finance roadmap

The Australian Sustainable Finance Institute has released a Sustainable Finance Roadmap, to realign the Australian financial services system so that more money flows to activities that will create a sustainable, resilient and inclusive Australian economy ().

The roadmap sets out sustainable finance reforms and related measures, including:

- mandatory climate-related financial disclosure requirements for large businesses and financial institutions

- developing an Australian sustainable finance taxonomy

- improving market supervision and enforcement of governance and disclosure standards

- identifying and responding to financial risks, for example through climate vulnerability assessments

- issuing Australian sovereign green bonds.

NSW environmental, social and governance review

Responsible investment involves considering environmental, social and governance issues when making investment decisions and influencing companies or assets (known as active ownership or stewardship).

A 2022 review of State Government investment funds looked at how funds managed by NSW Treasury Corporation on behalf of NSW Government entities, considered environmental, social and governance principles.

It also examined how the NSW Government processes and practices could be improved while promoting a better future and a resilient economy.

Priority recommendations from this review included:

- further developing decarbonisation and net zero approaches

- comprehensive public reporting

- clearer guidance on environmental, social and governance expectations.

A response to the review was published in 2023.

Sustainability disclosures

Sustainability disclosures are a way for organisations to report and act on their sustainability risks and opportunities, including environmental, social and governance risks.

Sustainability disclosure frameworks include:

- climate-related financial disclosures

- nature-related financial disclosures

- inequality and social-related financial disclosures.

There is a growing momentum behind improving sustainability-related disclosures, including climate-related and nature-related financial disclosures. These disclosures can provide valuable insights into current practices impacting the environment, add to the recognition of natural capital as a valuable asset category, and be a catalyst for investment in natural capital and nature positive initiatives. They can also highlight the economic and financial risks associated with depleting and degrading the environment.

The Australian Government has passed legislation to mandate sustainability reporting for large companies from January 2025. This will provide Australians and investors with greater information and certainty when it comes to considering their climate-related plans, financial risks and opportunities.

Mandatory climate-related financial disclosure requirements are expected to reduce greenwashing, as reporting climate-related information will become more standardised and transparent ().

In NSW, Treasury’s annual report framework requires government entities to include ‘sustainability’ as a mandatory heading in annual reports.

Disclosure information could also provide better understanding of how economic activity in one state may impact the environment in other parts of the country or overseas.

The increasing adoption of natural capital accounts also presents an opportunity to provide credible underpinnings for nature-related and climate-related financial disclosures, supporting benchmarking for the development of nature repair and restoration markets to operate with integrity.

The emergence of inequality and social-related financial disclosures will also encourage businesses to improve the identification, assessment and reporting of social and inequality issues. There is a strong relationship between the environmental, economic and social aspects of sustainable development ().

Climate-related financial disclosure

Climate-related financial disclosure is a reporting framework that organisations can use to identify and understand climate-related issues that influence how they do business.

Disclosures are structured around four thematic areas that represent core elements of how business and entities operate:

- governance

- strategy

- risk management

- metrics and targets.

The information is released (disclosed) publicly. The aim of this reporting is to increase transparency and accountability about the impacts of climate-related risks and opportunities on business strategies, financial planning and organisational management.

It is complemented by the final recommendations of the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, which, together with other guidance documents, provides a framework to support corporate reporting.

In Australia, climate-related financial disclosures will be mandatory from 1 January 2025, for many large Australian businesses and financial institutions. These businesses will be required to disclose information about climate-related risks and opportunities that could reasonably be expected to affect the entity’s cash flows, its access to finance or cost of capital over the short, medium or long term, in line with Australian Sustainability Reporting Standards. These requirements will be phased in for other businesses during 2026 and 2027.

For NSW Government entities, NSW Treasury has issued guidelines setting out minimum requirements for disclosing public sector entities’ material climate-related risks and opportunities, including the actions entities are taking to manage these issues.

NSW Government agencies will implement these requirements in a staged approach. Pilot statements have already been released by NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, Essential Energy and NSW Environment Protection Authority.

The NSW reporting framework is closely informed by the Australian Sustainability Reporting Standards, developed by the Australian Accounting Standards Board, with some modifications to reflect NSW Government circumstances and reporting entity capability and capacity.

See the for more information.

Nature-related financial disclosure

Nature-related financial disclosure is a reporting framework that organisations can use to identify and understand nature-related issues that are connected to how they do business.

These issues fall into four categories:

- dependencies – how the organisation depends on nature (for example, it may need water for processing materials)

- impacts – that the organisation causes or contributes to (such as pollution)

- risks – to the organisation that result from their dependencies and impacts (such as fines or loss of reputation)

- opportunities – to benefit nature and to mitigate negative impacts (for example, bush restoration after a mining operation).

The information is released (disclosed) publicly. The aim of this reporting is to increase transparency and accountability about nature-related risks and opportunities and encourage nature positive outcomes.

This reporting is supported by the Global Biodiversity Framework. The framework’s Target 15 is a key driver, committing signatories, including Australia, to ensure that businesses monitor, assess and disclose their biodiversity impacts.

It is complemented by the final recommendations of the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) which, together with other guidance documents, provides a voluntary, market-led framework to support corporate reporting.

The Australian Government has published the TNFD Pilots – Australian case study report to help organisations undertaking TNFD-aligned risk and opportunity assessments. The report details how piloting Australian businesses approached their assessments.

The TNFD framework is currently voluntary, noting the Australian Government has outlined its intention to improve market supervision and enforcement as part of the Sustainable Finance Roadmap.

Future opportunities

Environmental markets for nature positive outcomes

There is an emerging emphasis on nature positive outcomes, where nature is being repaired and regenerated, and biodiversity decline is halted and reversed.

Viewing nature as a valuable collection of assets highlights the need to invest in nature, as opposed to simply conserving it.

Increasing investment in nature positive initiatives is being driven by several factors.

The first is the move towards legislated nature markets, such as the Commonwealth Nature Repair Market underpinned by the Nature Repair Act 2023. Such markets are not designed around regulatory compliance but instead are designed to foster voluntary investments in actions to increase and improve natural capital.

Nature investments are expected to be increasingly relied on in the future for natural capital replacement, restoration and improvement, as the quantum of investment required is likely to far exceed the capacity of government to take sole responsibility.

For example, several attempts have been made to identify and quantify the funding requirements likely to be needed to meet restoration and improvement targets, globally (Financing Nature: Closing the Global Biodiversity Financing Gap - Paulson Institute) and for Australia (Blueprint to Repair Australia’s Landscapes).

The Australian and NSW Governments jointly hosted the Global Nature Positive Summit in October 2024, to help build momentum towards increasing investment in nature, and repairing and restoring natural environments. The forum connected decision-makers from across sectors on:

- economic settings needed to increase investment in nature

- best practice and pathways for program implementation

- innovative tools and approaches underway in Australia and the Pacific that enable nature positive outcomes.

Taking action to repair nature

The Australian Government has set out its commitment to reform the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 to deliver better environmental protections that support nature positive initiatives through its Nature Positive Plan: better for the environment, better for business.

In NSW, two recent statutory reviews considered the State’s primary biodiversity laws: the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 and the native vegetation provisions of the Local Land Services Act 2013.

In July 2024, the NSW Government released its response to the reviews, NSW plan for nature. The plan aims to:

- reform the biodiversity offsets scheme

- end excess land clearing

- strengthen environmental protections.

It also outlines the legislative, policy and program directions the NSW Government commits to take to respond to the statutory reviews and deliver on its commitments.

The reviews and the plan focus on the performance of the Biodiversity Offsets Scheme, and opportunities for investment in natural capital and the development of a voluntary market to improve biodiversity outcomes.

Under the plan, the NSW Government has piloted and implemented a natural capital accounting framework and launched the Natural Capital Accounting Hub.

The NSW Government has also committed to work with the Australian Government on the development of the national Nature Repair Market and national carbon market, and design NSW natural capital programs and projects to leverage national schemes.

The Nature Repair Market, underpinned by the Nature Repair Act 2023, is an Australian government initiative to restore and protect the environment. It encourages nature positive land management practices that deliver improved biodiversity outcomes ().

The scheme establishes a marketplace where individuals and organisations can undertake nature repair projects to generate a tradeable certificate (). The market is expected to open in 2025.

Climate change

Climate change will increase stress on ecosystem services and have a significant effect on many activities. These include agriculture, forestry, fisheries, water security, energy security, infrastructure, transport, health, tourism, finance and disaster risk management.

The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2024 identified extreme weather as one of the top risks most likely to present a material crisis (). Biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse have also been consistently ranked as mid- to high-level global risks in previous reports.

The Australian National Outlook 2019 report shows that stronger action on environmental measures does not necessarily come at the expense of economic outcomes ().

See the topic for more information.

Impact of climate change on the NSW economy

The health of the NSW economy is strongly linked to the environment and the natural resources and ecosystem services it provides. Climate change is already affecting the NSW economy and will continue to do so.

The 2021–22 NSW Intergenerational Report is a snapshot of the future to inform future policies (). The report projects 40 years ahead to 2061 to understand how the State’s population, economy and finances may change based on global and local trends and current policies.

The report findings include:

- Climate change is likely to increase the risk of extreme weather events such as bushfires and floods, having a significant impact on livelihoods and the State’s productivity ().

- More frequent and severe natural disasters could cost NSW between $15.8 billion and $17.2 billion per year on average by 2060–61 ().

- If climate change is more severe than expected and temperatures increase by 2.8°C by 2060–61, the NSW economy would lose $4.5 billion in annual income by 2060–61 compared to the moderate warming scenario ().

- If warming is limited to a 1.5°C increase, total economic income in NSW would be $3.8 billion higher every year by 2060–61 ().

There could also be significant costs from rising sea levels, heatwaves and the impact of changing climatic conditions on agricultural production.

This has flow-on effects on the economy, such as:

- changes to the productivity of primary industries, including fisheries and aquacultures, due to increasing ocean temperatures and marine heatwaves ()

- reduced agricultural output in the Murray–Darling Basin due to extreme weather events, such as droughts, heatwaves, cyclones and floods ()

- property loss and damage, increased infrastructure and service costs, and risks to financial stability ()

- impacts on health and wellbeing, which can affect people’s ability to work and contribute to society and increase demand for healthcare services ()

- damage to critical infrastructure, affecting transport, electricity, water, telephone and Internet services, which can disrupt businesses and delivery of services ()

- changes in land use, the change in seasonal conditions, such as increasing temperature and changed rainfall patterns may render the land unsuitable for agriculture ().

See the and topic for more information.

Image source and description

Topic image:Bundjalung and Gumbaynggirr Country–Harwood, Clarence River. Photo credit: Stephen Ward/DPI (2020).Banner image:Topic image sits above Butjin Wanggal Dilly Bag Dance by Worimi artist Gerard Black. It uses symbolism to display an interconnected web and represents the interconnectedness between people and the environment.

Image source and description

Topic image:Bundjalung and Gumbaynggirr Country–Harwood, Clarence River. Photo credit: Stephen Ward/DPI (2020).Banner image:Topic image sits above Butjin Wanggal Dilly Bag Dance by Worimi artist Gerard Black. It uses symbolism to display an interconnected web and represents the interconnectedness between people and the environment.