Image source and description

Main imageWorimi artist Gerard Black’s artwork depicts the Aboriginal Peoples Knowledge Group’s Gulamon (also known as Coolamon), which serves as a ceremonial vessel used in each gathering, carrying cultural meaning and connection. This Gulamon was crafted from a tree on Gomeroi Country by one of the Group’s members.Background imageTheme image sits above Butjin Wanggal Dilly Bag Dance by Worimi artist Gerard Black. It uses symbolism to display an interconnected web and represents the interconnectedness between people and the environment.

Image source and description

Main imageWorimi artist Gerard Black’s artwork depicts the Aboriginal Peoples Knowledge Group’s Gulamon (also known as Coolamon), which serves as a ceremonial vessel used in each gathering, carrying cultural meaning and connection. This Gulamon was crafted from a tree on Gomeroi Country by one of the Group’s members.Background imageTheme image sits above Butjin Wanggal Dilly Bag Dance by Worimi artist Gerard Black. It uses symbolism to display an interconnected web and represents the interconnectedness between people and the environment.

Main image

Worimi artist Gerard Black’s artwork depicts the Aboriginal Peoples Knowledge Group’s Gulamon (also known as Coolamon), which serves as a ceremonial vessel used in each gathering, carrying cultural meaning and connection. This Gulamon was crafted from a tree on Gomeroi Country by one of the Group’s members.

Background image

Theme image sits above Butjin Wanggal Dilly Bag Dance by Worimi artist Gerard Black. It uses symbolism to display an interconnected web and represents the interconnectedness between people and the environment.

A Voice of Country

The APKG collective voice – we invite you to ngarrangga ‘listen’.

A Voice of Country describes ways Aboriginal people identify and mentions aspects of our shared history and world views. The chapter concludes with acknowledging the connectedness, what has come before us, and the need to ngarrangga ‘listen’ (from the Gathang language).

Identity and terminologies

The key to developing respectful relationships with Aboriginal people is knowing how people identify as an Aboriginal person, and the terminology used for the original people of this Country.

Indigenous Australian peoples are of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent; who identify as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander and are accepted as an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person in the community in which they live or have lived.

It is important to understand that Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people may identify with one or more Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander nations and/or language groups.

The original people who occupied the land now known as New South Wales, are referred to by various terms interchangeably such as: Aboriginal, Australia’s First Peoples, First Nation People, Aboriginal people, Indigenous people, Black, Koori, Goori and by their bloodline ancestors (for example, Dhanggati, Birrbay, Gamilaraay, Gomeroi, Bundjalung, Nyangbul, Anaiwan, Wiradjuri, Nguyampaa, Barkindji and Ngiyampaa).

It is respectful to ask what terms are acceptable when referring to a specific Aboriginal group or community.

It is through the knowledge of past historical events in our shared history that people can gain a deeper understanding of the complexities of Aboriginal peoples connection with their culture, Country, Lore and each other.

History

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are recognised as the oldest continuous culture on the planet.

Before colonisation in 1788, there were more than 250 nation groups; each with several different clans and language groups, which formed a diverse tapestry of custodianship of Lore and Country across this continent now known as Australia.

Aboriginal peoples way of life was disrupted by the waves of British invaders. In the quest to colonise, they failed to see the sophisticated societies with people living sustainable lifestyles by using technologies to farm and manage the land and waterways.

Relationality was and will always be at the forefront of Aboriginal cultural practices and Lore, governing the interaction between all entities, creating a harmonious environment for all to thrive.

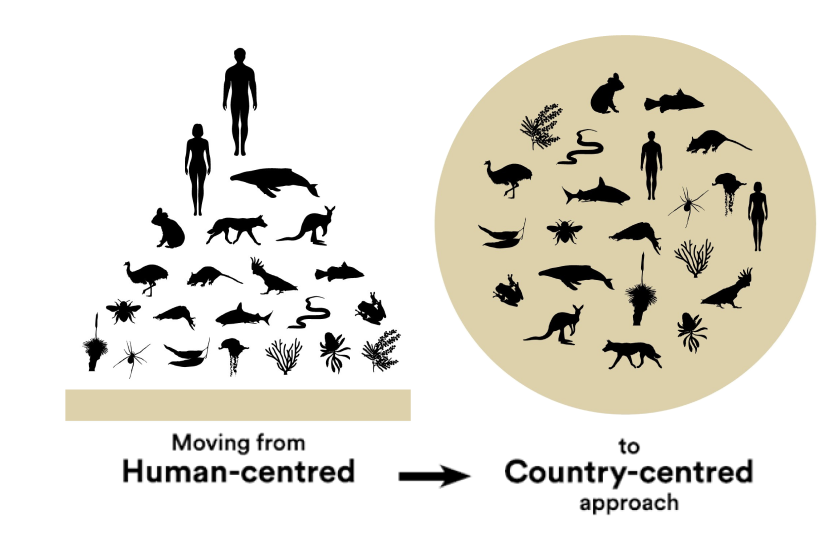

Through colonisation, Western industrialisation brought to these shores a system that created an imbalance to the land. The human-centred, hierarchical views of the invaders conflicted with the Country-centred views of the original peoples, and resulted in conflict, trauma and a disruption to people living in harmony with Country.

The Country-centred approach places equal importance on all that Country holds. Aboriginal custodians, as carers of Country, safeguarded the continuation of cultural practices, met cultural obligations and upheld rights to self-determine how to maintain, protect and conserve Country when working with other authorities.

Figure V1.3 is a visual representation of the human-centred approach as opposed to the Country-centred approach. Working in today’s reality, Aboriginal people honour their ancestors by safeguarding the continuation of cultural practices; meeting their cultural obligations; upholding their rights as a voice for and with Country; and self-determining how to maintain, protect and conserve Country when working with other authorities.

Figure V1.3: Examples of human-centred and Country-centred approaches

Self-determination

The following articles speak to self-determination and the rights of indigenous people as a way forward to uphold their cultural practices that includes caring for Country.

The EPA, in respectful relationship and partnership with the APKG, can ensure the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Australia (New South Wales) are not just words on a page but meaningful interactions between all environmental custodians to protect the rights of Aboriginal people in NSW to:

- practise and revitalise their culture

- maintain and strengthen their distinctive spiritual relationship with their traditionally owned or otherwise occupied and used lands, waters and coastal seas.

In doing so, there is a stronger movement to conserve and protect the natural environment and the preservation of Aboriginal cultural values, principles and practices for all future generations.

After being voted against in 2007, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples () was adopted in 2008 on behalf of Australia by the former Prime Minister, the Hon. Kevin Rudd.

The 46 articles of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples recognise a standard of achievement to be pursued in the true spirit of partnership and mutual respect and detail Indigenous peoples’ rights to be distinctly different and have aspirations to self-determine their cultural activities and life aspirations.

Below are five of the 46 articles of note:

Article 3

Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.

Article 11

- Indigenous peoples have the right to practise and revitalize their cultural traditions and customs. This includes the right to maintain, protect and develop the past, present and future manifestations of their cultures, such as archaeological and historical sites, artefacts, designs, ceremonies, technologies and visual and performing arts and literature.

- States shall provide redress through effective mechanisms, which may include restitution, developed in conjunction with indigenous peoples, with respect to their cultural, intellectual, religious and spiritual property taken without their free, prior and informed consent or in violation of their laws, traditions and customs.

Article 25

Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain and strengthen their distinctive spiritual relationship with their traditionally owned or otherwise occupied and used lands, territories, waters and coastal seas and other resources and to uphold their responsibilities to future generations in this regard.

Article 26

- Indigenous peoples have the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired.

- Indigenous peoples have the right to own, use, develop and control the lands, territories and resources that they possess by reason of traditional ownership or other traditional occupation or use, as well as those which they have otherwise acquired.

- States shall give legal recognition and protection to these lands, territories and resources. Such recognition shall be conducted with due respect to the customs, traditions and land tenure systems of the indigenous peoples concerned.

Article 33

- Indigenous peoples have the right to determine their own identity or membership in accordance with their customs and traditions. This does not impair the right of Indigenous individuals to obtain citizenship of the States in which they live.

See the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples for more information.

Through mutual respect and actions, we can honour these articles, breathe life into these words and be resolute in preserving the rich cultural values and principles of our people. In the present, we create the past and plant the seeds for the future. The time has come for thinking deeply about what we sow for our tomorrow’s children and how our legacy of preserving culture and respecting land will support them to dream, strive and grow into our future leaders. What do we need to know and understand to move forward?

Moving forward

In spirit of moving forward, we acknowledge the past and present societal structures in which everything is connected and everything is relational.

Operating through a set of principles that fostered cooperation rather than competition, our people lived in harmony with nature, which has a natural rhythm and balance to it and humans lived in synergy, protecting Country.

The principles of all nature-based practises recognise spirit and the sacredness of life, through which ceremonies, song and dance reaffirmed our place and identity.

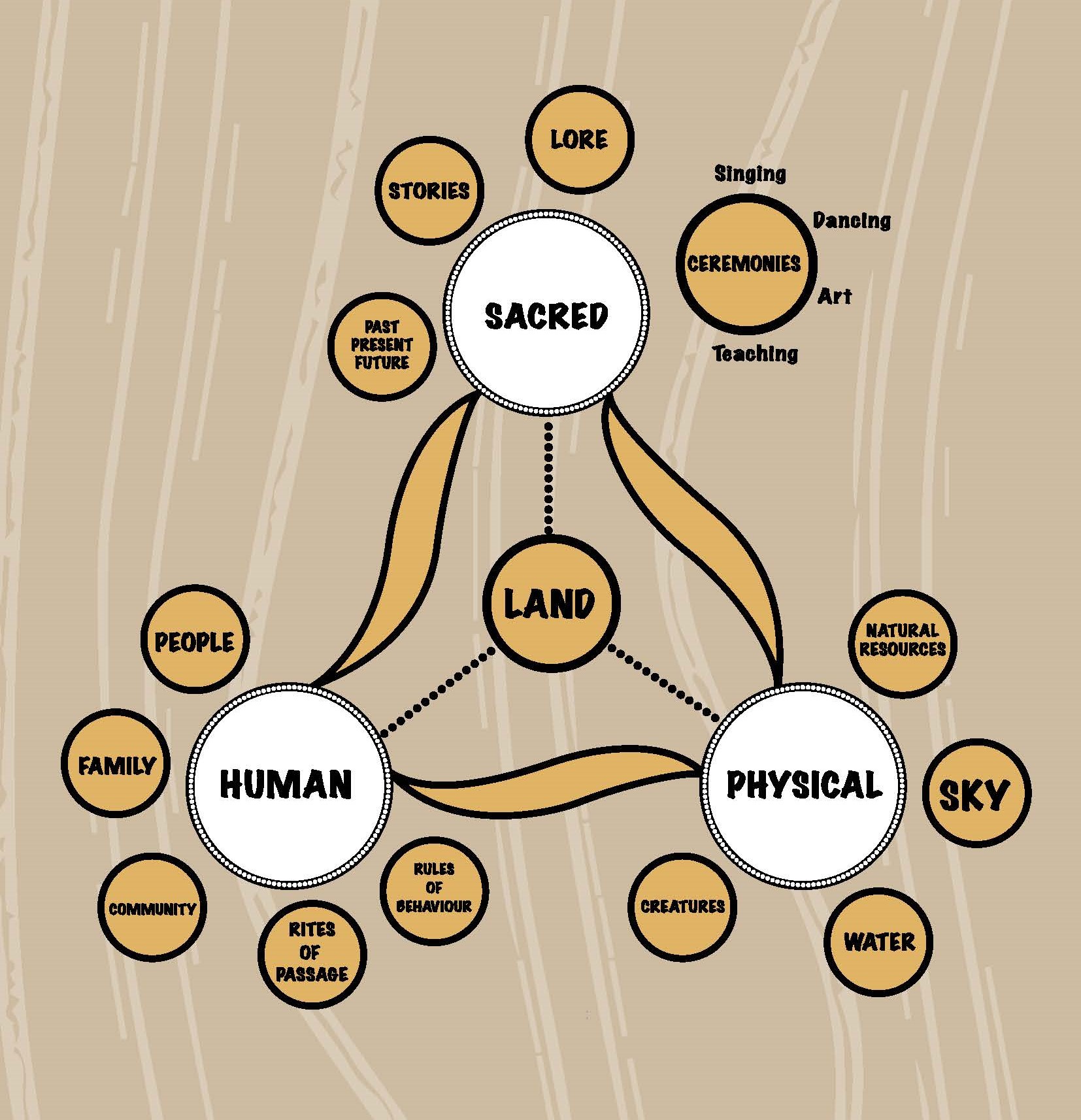

Country was the source of identity and there was a duty to protect and care for it. To maintain it and nurture it for all generations to come. Our role was and is to recognise our place as human beings, to foster a deep sense of connection and belonging to keep things in balance (see Figure V1.4).

The APKG invites other stakeholders in the protection of our environment to work with us within a cultural framework that honours our connectedness.

Figure V1.4: Connectedness

In moving forward, we acknowledge the past.

We also acknowledge the collaboration between the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff of the EPA and the inaugural APKG membership; Department of Planning, Industry and Environment, the NSW Aboriginal Land Council, and two independent members: Wally Stewart, a Walbunja man from the south coast of NSW, and Associate Professor Bradley Moggridge, a Kamilaroi water scientist. it is through working with a shared goal that has led us to where we are today.

The inclusion of Aboriginal voices and cultural views in the State of Environment 2021 report allowed the current APKG to have a collective voice to work collaboratively with the EPA to ensure their Statement of Commitment is upheld and enshrined in policy and legislation.

We need to ngarrangga ‘listen deeply’ to each other; walk together, value our differences, acknowledge our strength and have the courage to take action to implement change wherever it is required, for the betterment and care of Country and all peoples.

References

Susan Moylan-Coombs 2024, Connectedness: the three worlds, the Gaimaragal Group