Overview

Australia is home to many animals found nowhere else on earth. About 45% of birds, 87% of mammals, 94% of amphibians, 24% of fish and 93% of reptiles are unique to Australia ().

The animal species that occur naturally in a place are described as ‘native’. Animals that are native to a specific region and not found anywhere else are called ‘endemic’.

NSW has a rich biodiversity, much of which is recognised as being internationally significant.

Native animals are important as they add to the variety of life on earth. They also provide many important ecosystem services that plants, other animals and humans rely on to survive. These services include:

- pest control

- pollination

- seed dispersal

- helping vegetation grow

- providing healthy resources, like clean water

- enriching and creating soil.

Native animal species play an important role in preserving and protecting the health of the environment. For example:

- While foraging, brush turkeys can move up to 200 tonnes of soil per hectare each year (). This soil disturbance helps plants to colonise new areas.

- Old forage pits dug by bandicoots and goannas trap litter and rainwater, which eventually breaks down to enrich the soil ().

When a species declines in numbers or distribution, or dies out altogether, these services can be reduced or wiped out (). Keeping native animals healthy and abundant is therefore an important goal for NSW.

Native animals are of cultural value to Aboriginal peoples. For example, totem animals are central to Aboriginal spirituality and cultural identity. Individuals may be connected to one or more totemic species through kinship. These are often expressed through ceremonies, art, stories and language (). Totems serve as powerful symbols, connecting people to the land and their ancestors ().

Aboriginal peoples recognise ways that all nature is connected, and the importance of animals in preserving the balance of nature ().

Totem animals teach respect for nature. Aboriginal peoples’ respect for animals has preserved the balance of nature for centuries and ensured the land’s sustainability for future generations.

Threats to animals

Since European colonisation, there has been a steady decrease in biodiversity in NSW (). Biodiversity means the variety of life on earth.

There has also been an increase in the number of species that are threatened and extinct.

These trends extend to both land- and water-based ecosystems, with invertebrates, amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals and fish all included on lists of threatened species.

In 2024, there are more than 300 animal species in NSW that are threatened and at risk of extinction (See Table B2.3).

Key threats to animals in NSW include:

- climate change, for example, their habitat becomes too hot or cold for them

- weeds, which compete with native plants and animals and push them out of their habitat

- being preyed on by invasive species like cats and foxes, or competing for habitat with invasive animals like rabbits and goats

- changes in fire regimes, such as an increase in the frequency or intensity of wildfire, that may kill animals or cause loss or significant modification of habitat

- diseases that weaken or kill native animals

- loss of habitat where animals can find shelter, food and safety, due to people clearing native vegetation for urban, industrial or agricultural development

- pollution, including light and noise pollution, and pollution from pesticides

- traffic accidents from tractors, trucks and cars as part of agricultural and urban development

- river regulation, meaning there is less water for animals to live in or drink

- illegal hunting.

These threats may also work together and have led to significant reductions in the size of animal populations, and in their distribution and health. Many species live in smaller ranges than they previously did.

Legislation and management framework

Table B2.1 outlines current key legislation, policies and strategies related to native animals and their management in NSW. These are administered by State government agencies, including:

- NSW Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (NSW DCCEEW)

- Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD)

- Local Land Services (LLS)

- National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS)

- NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA)

- Biodiversity Conservation Trust (BCT).

Recent initiatives to protect native animals in NSW include:

- the NSW Saving Our Species program (NSW DCCEEW)

- the NSW Assets of Intergenerational Significance program (NSW DCCEEW)

- the NSW Biodiversity Offsets Scheme (NSW DCCEEW)

- the NSW Private Land Conservation program (BCT)

- the Commonwealth Threatened Species Action Plan 2022–32

- the Commonwealth National Landcare Program (delivered by LLS in NSW)

- NPWS Threatened Species (Zero Extinctions) Framework

Table B2.1: Current key legislation, policies and strategies relevant to native animals and their management in NSW

| Legislation or policy | Summary |

|---|---|

| Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 | Aims to protect biodiversity and foster a productive, resilient environment while enabling ecologically sustainable development. Also creates the Biodiversity Offsets Scheme and Saving Our Species Program. |

| Biosecurity Act 2015 (Commonwealth) | Manages biosecurity threats to plans, animal and human health in Australia and Australian territories. |

| Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) | Protects the biodiversity of land-based plants and animals, and the environment, while enabling ecologically sustainable development. |

| Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 | Governs planning administration and laws, development assessments, environmental assessments, building certification, infrastructure finance, appeals and enforcement. It is the primary land use planning statute in NSW. |

| Fisheries Management Act 1994 | Legislates the management of fishery resources and their habitats in NSW. It also legislates that the fishing needs and traditions of Aboriginal people are appropriately considered in the management of fisheries resources. |

| Forestry Act 2012 | Establishes the framework for integrated environmental approvals for native forestry operations on Crown timber lands. |

| Local Land Services Act 2013 | Governs management of natural resources, biosecurity and agricultural production on private rural land. |

| National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 | Aims to conserve the natural and cultural heritage of NSW through the establishment of national parks and reserves. |

| Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997 | Aims to achieve the protection, restoration and enhancement of the quality of the NSW environment. It enables the Government to create protection of the environment policies (PEPs), set environment protection licensing arrangements and perform other environment protection functions. |

| Australia’s Strategy for Nature 2024–2030 | Aims to halt and reverse biodiversity loss in Australia by 2030. |

| NSW Koala Strategy | Supports targeted investment and conservation actions that will protect koalas. |

| NSW plan for nature | Sets out the NSW Government response to the reviews of the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 and the native vegetation provisions of the Local Land Services Act 2013. |

| Threatened Species Action Plan 2022–2032 (Commonwealth) | Sets out targets and actions to protect, manage and restore Australia’s threatened species and important natural places. |

| Threat abatement plans (Commonwealth) | Provide for research, management and other actions required to assist the long-term survival in the wild of affected native animals. |

| Zero extinctions – National parks as a stronghold for threatened species recovery | Outlines a series of actions designed to secure and restore threatened species populations on the national park estate. |

Notes:

See the Responses section for more information about how protection of native animals is managed in NSW.

Related topics: | | | | |

Status and trends

NSW animal indicators

This report uses five indicators to assess the status and trends regarding the abundance, distribution and population of native animals in NSW (see Table B2.2).

- Number of threatened species listed reports the status and trends of the number of species listed as critically endangered, endangered and vulnerable in the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (see Threatened species).

- Native mammals: population and distribution reports on the status and trends in the populations and distribution of native mammals in NSW (see Native mammals).

- Native birds: population and distribution reports on the status and trends in the populations and distribution of native birds in NSW (see Native birds).

- Native fish communities reports on the status and trends regarding native fish in NSW (see Native fish).

- Invasive animal species: distribution and impact reports on the status and trends of invasive species (introduced animals such as rabbits, foxes and carp) on land and in water. It also reports on their distribution and impact on native animals and the environment (see Invasive species).

These indicators (apart from ‘invasive animal species: distribution and impact’) align to the ‘biosphere integrity’ planetary boundary. Globally, this boundary has been crossed (see page for more information).

Table B2.2: Animals indicators

| Indicator | Environmental status | Environmental trend | Information reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of threatened species* listed | Getting worse | Reasonable | |

| Native mammals: population and distribution | Getting worse | Limited | |

| Native birds: population and distribution | Getting worse | Reasonable | |

| Native fish communities | Getting worse | Reasonable | |

| Invasive animal species: distribution and impact | Getting worse | Reasonable |

Notes:

*Threatened species encompasses those listed as critically endangered, endangered and vulnerable in the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.

Indicator table scales:

- Environmental status: Good, moderate, poor, unknown

- Environmental trend: Getting better, stable, getting worse

- Information reliability: Good, reasonable, limited.

See to learn how terms and symbols are defined.

See the page for more information about how indicators align.

Threatened species

Animal species are listed under state and federal legislation as ‘threatened’, meaning actions are needed to stop them going extinct.

This section describes the status of native animal species listed as threatened in the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 or the Fisheries Management Act 1994.

The number of threatened animal species listings in NSW has increased by 18 (see Table B2.3) since the State of the Environment 2021. Changes in totals and numbers of threatened species listings do not represent the overall status of biodiversity, but are a useful indicator.

A species becomes threatened due to the threats and pressures it experiences. Some key threatening processes that pose threats to NSW native animals include:

- climate change, such as increasing temperatures and increasing frequency of drought

- invasive plants and animal species (also known as feral animals)

- changing fire patterns

- pathogens or disease

- habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation.

See the key threatening processes for all listed in the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.

A species is considered threatened if it is facing high to extremely high risk of extinction. This can happen when:

- there is a reduction in its population size

- it has a restricted geographical distribution

- there are few mature individuals.

A decision to list a species as threatened in the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 or the Fisheries Management Act 1994 is made in accordance with criteria developed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

In NSW, the NSW Threatened Species Scientific Committee decides if a species should be listed as threatened in the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. The Fisheries Scientific Committee has the same responsibility for fish and aquatic invertebrate species listed as threatened in the Fisheries Management Act 1994.

A Common Assessment Method is being also used across the Australian Government and all states and territories. This means there will be consistent assessment and listing of species in Australia, more frequent reviews of the current listing, and a more comprehensive picture of how species are doing across the continent.

As at June 2024, 343 threatened animal species were listed under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 and Fisheries Management Act 1994. Since 2020, there has been an increase in the number of listings for all animal taxa (categories), except for marine mammals. Listings increased after the 2019–20 bushfires, as the fires reduced the range and numbers of many species and additional funding and resources were allocated to listing assessments by governments.

Table B2.3 compares listings in 2020 to those in 2024.

Table B2.3: Numbers of threatened animals listed in the Biodiversity Conservation Act and Fisheries Management Act in 2020 and 2024

| Animals | 2020 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|

| Mammals | 57 | 59 |

| Marine mammals | 7 | 6 |

| Birds | 126 | 130 |

| Amphibians | 29 | 30 |

| Reptiles | 44 | 50 |

| Fish | 39 | 43 |

| Invertebrates | 23 | 25 |

| Total | 325 | 343 |

Notes:

In this table ‘threatened’ means all species listed as ‘critically endangered’, ‘endangered’ and ‘vulnerable’.

Nine species of fungi are also listed under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. The number has not changed since 2020.

Although more species are listed as threatened in 2024 than in 2020 in NSW, this does not necessarily mean that the species are facing more threats.

Some species have been listed as threatened because:

- there has been an increase in threats and pressures the species faces

- new or improved information about the species has become available, so there is now enough data to accurately assess them as threatened.

New data also means some species are being delisted.

The listing process is scientifically rigorous which helps ensure decisions are made based on the latest species information.

Having more accurate information means that planning and conservation actions can be developed before animals decline to critical levels or become extinct.

In NSW, about 1,000 species and ecological communities are known to be threatened and at risk of extinction. Over time, the numbers of critically endangered and endangered animals and endangered populations listed have increased. Meanwhile, the number of extinct animals listed has fallen from 81 in 1995 to 76 in 2024.

These trends in species listings are shown in Figure B2.1.

Figure B2.1: Number of threatened animal species listings in NSW 1995–2024

Notes:

Years up to and including 2023 include data from 1 January to 31 December. The year 2024 only includes data for 1 January to 30 June.

NSW residents are also gaining more knowledge of native animal species in NSW that are in serious decline and at risk of becoming extinct (see Table B2.4).

When considering species that are of significance to Aboriginal peoples, resources for their protection are limited if the species is not currently listed as threatened.

See the topic for more information on how Aboriginal peoples value native species and their importance locally.

Table B2.4: NSW residents’ awareness of risks to native animals

| Question and possible responses | Percentage of community choosing the response | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thinking about native animal species, as far as you know, would you say | 2015 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

| There are no native animal species in NSW in serious decline and at risk of becoming extinct | 4% | 6% | 6% | 6% |

| There are native animal species in NSW in serious decline and at risk of becoming extinct | 68% | 82% | 84% | 83% |

| Not sure, don’t know | 28% | 11% | 10% | 12% |

| Sample (n) | 2,000 | 1,901 | 2,063 | 2,060 |

Notes:

See the topic for more information about this survey.

Importance of diversity

Measures of animal diversity include phylogenetic and functional diversity.

Phylogenetic diversity

Phylogenetic diversity considers how closely or distantly species are related to each other in an evolutionary tree.

For example, koalas (family Phascolarctidae) have a low phylogenetic diversity because they have no living relatives, while kangaroos (family Macropodidae) have several living relatives, including wallabies and quokkas.

We can estimate the proportion of the evolutionary tree that is expected to still exist in 100 years if certain species survive while others become extinct. Some species have no close relatives, and losing such distinctive species would result in a greater loss of phylogenetic diversity than losing a species with lots of close relatives ().

Phylogenetic diversity for tetrapods (frogs, mammals, reptiles and birds) expected to survive in 100 years has declined from 92% in 2017 to 91% in 2022. This is because in 2022 more species risked extinction than in 2017 (). For example, the koala, which has no close living relatives, shifted from being listed as vulnerable to endangered in 2022.

Functional diversity

Functional diversity means the range of activities a species performs in ecosystems and their interactions with their environment. For example:

- an understorey plant may provide shelter for ground-dwelling animals and rely on an insect to pollinate its flowers

- a tree may rely on a bird to eat its fruits and excrete them, releasing its seeds into the soil

- a freshwater fish may host and transport mussel larvae.

These relationships can break down if a species declines or dies out.

Only 50% of species listed as threatened (in 2022) are predicted to still be living in 100 years’ time ().

See the NSW biodiversity outlook report 2024 for more information.

There are many examples of how well-implemented and resourced conservation actions can improve a species’ status. For example:

- northern populations of the Booroolong frog are recovering due to captive breeding and reintroduction to the wild, after nearly being wiped out during the 2017–20 droughts ()

- yellow-footed rock wallaby numbers have increased from 100 animals in 2003 to 299 in 2023, due to actions to improve their habitat and efforts to control foxes that prey on them ()

- for the first time in 20 years, glossy black-cockatoos have been discovered in their previous range on the NSW Mid North Coast, with adults successfully nesting and raising chicks ().

However, management and conservation actions will not be enough to save many species without resolving key threats, such as habitat removal and climate change.

See the topic for more information about how NSW protects land.

Invertebrates

Australia is home to about 320,000 species of invertebrates (), including bugs, beetles and snails. Of these, only 110,000 have been identified ().

Invertebrates are the foundation of terrestrial and aquatic food chains across the planet. They contribute to the health of many ecosystems due to, for example, pollination, decomposition and nutrient cycling.

Invertebrates are a vital, but sometimes forgotten, part of earth’s biodiversity. Their contributions are often underestimated, and the extent of their ecological interactions are poorly understood ().

When insect populations decline, so too do the populations of larger species that eat them. For example, migrating bogong moths are a primary seasonal food for the endangered mountain pygmy possum ().

The bogong moth has been in decline since the 1980s but had a huge population crash of up to 95% after the 2017 drought ().

In the following years, researchers found mountain pygmy possums had increasing pouch litter loss. This early death of young possums was linked to the significant decrease in bogong moths ().

In 2022, bogong moth numbers started to rebound. This is a positive development for the moths and the mountain pygmy possums ().

The bogong moth is of immense cultural significance and a central part of the Dreaming for many Aboriginal peoples of south-eastern Australia ().

For more than 2,000 years this species was a major seasonal food source in the NSW Southern Highlands, when people would travel hundreds of kilometres to gather for intertribal corroborees (; ).

Wetland fauna

Fresh water is vital to animal life. In a country as dry as Australia, fresh water is an important resource.

In NSW, natural flows and the strategic release of water from impoundments to the environment help to protect rivers and wetlands and the species that depend on them.

Monitoring of inland wetlands has shown that some wetland-dependent waterbirds, frogs and freshwater turtles have benefited from the release of environmental water.

Wetland species can be useful bioindicators, meaning their presence can show the health of the ecosystems they live in. For example, the population health of some species of waterbirds and frogs can be used to:

- identify the quality of water

- identify eutrophication, that is, when excessive growth of microorganisms takes oxygen out of the water ()

- assess whether water flows are effective ().

See the topic for more information on water flows and population trends.

Native mammals

Australia has registered the largest loss of species in the world in recent times. In the past two centuries, Australia has lost more mammal species than any other continent, contributing to about one-third of mammal extinctions globally ().

There has been a rapid extinction of native species, and large and continuing declines in their abundance and range (). More than 35% of Australian mammal species have declined in distribution or become extinct in the past 200 years (see Figure B2.2).

Figure B2.2: Number of native mammal species that have declined in distribution or become extinct in the past 200 years

Notes:

Presumed extinct – 100% contraction in distribution

Severe decline – 50–<100% change in distribution

Moderate decline – 25–<50% change in distribution

No significant decline – less than 25% change in distribution

n = total number of species recorded as inhabiting NSW at the time of European colonisation. It does not include species regarded as ‘vagrants’ (occasional or accidental sightings of species well outside their normal range).

Short-term contributors to this decrease are the 2017–19 drought and 2019–20 bushfires. In some cases, animals are recolonising areas formerly burnt by the bushfires, although recovery is slower for species that were threatened or in decline before the bushfires, have specialised diet or habitat needs and have slower life histories ().

Longer-term declines have been linked to invasive species. For example, cats and European red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) have been the main drivers for at least two-thirds of terrestrial Australian mammals becoming extinct, and have also been the cause of declining distribution and density of many mammals (; ).

Keeping track of koalas

Koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) in NSW are facing a range of threats, including:

- habitat loss and fragmentation

- climate change

- bushfires

- disease

- declining genetic diversity

- vehicle strikes

- dog attacks.

These factors have resulted in significant population decline, with koalas listed as ‘endangered’ in NSW.

Koalas are an iconic Australian species, with deep cultural significance to Aboriginal peoples.

They are listed under the Australian Government’s 110 priority species in the Threatened Species Action Plan 2022–2032. Selection criteria for a species’ inclusion on this list includes:

- severe or imminent threat of extinction

- whether recovery actions benefit other threatened species sharing the same habitat are feasible and cost effective

- cultural significance

- whether the animal has close relatives or is not found anywhere else

- whether the animal is representative across landscapes, seascapes and jurisdictions.

In NSW, koala surveys are being undertaken to:

- identify population trends

- understand threats and how to mitigate them

- prioritise conservation actions.

Koalas are an umbrella species

Umbrella species are those whose protection benefits many other plant and animal species sharing the habitat ().

Protecting koalas and their habitat improves conservation of other native species (). For example, koala habitat often overlaps with the habitat of barking owls, wombats and wedge-tailed eagles. Actions to protect koala habitat therefore also protect the habitat of these other species.

Conservation actions that control threats to koalas, such as bushfires, pollution and invasive predators, can also benefit many other native species.

NSW Koala Strategy

The NSW Government has prioritised koala research under the NSW Koala Strategy 2021–26, which is a plan to:

- identify and prioritise key knowledge gaps – a key knowledge gap is one that, as a result of being addressed through research, will likely increase the effectiveness of koala conservation actions and/or their likelihood of implementation

- outline the process by which research grant applications will be sourced, including assessment criteria

- outline how the progress and outputs of the individual research project will be monitored and evaluated

- outline how progress and outputs of the research plan will be monitored, evaluated and revised over the life of the plan.

Under the strategy, NSW Government scientists are working on applied research (research that aims to find a solution to a known problem), to improve the knowledge of koalas and how best to manage them to support conservation actions. This includes improving knowledge on koala population locations, numbers, habitat requirements, threats and how to manage them effectively. This applied research helps inform policy development and ensures koala conservation decisions are based on the best available information, with minimum uncertainty.

The 2024 discussion paper, Reviewing the NSW Koala Strategy, details the research and monitoring being undertaken for koala populations.

Bushfires impact koala populations

In 2022, koala populations in Queensland, NSW and the ACT were listed as endangered for the first time (). Up to 80% of koalas were lost from some areas affected by bushfires in NSW ().

While these results are grim, follow-up surveys in the past three years have shown that koalas are recolonising unburnt and partially burnt sites from the 2019–20 bushfires ().

Koala monitoring in north-east NSW

Since 2015, the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development has annually monitored koala populations in the hinterland forests of north-east NSW.

The study has recorded koala bellows (a vocal sound) and other evidence of koalas at 224 sites over 1.7 million hectares (m ha). The study has taken place on various forest sites in State forests and national parks, with better quality and poorer quality habitat.

Between 2015 and 2021, koala occupancy was stable, with most sites being occupied (see Figure B2.3).

Figure B2.3: Regional koala occupancy at monitoring sites, 2015–21

Notes:

This data accounts for imperfect detection and environmental factors, such as elevation, at monitoring sites.

CL=confidence level

These results indicate a large group of separate koala populations spread across State forests and national parks.

Through the NSW Koala Strategy 2021–26, the NSW Government is undertaking a baseline survey of the koala population and a sentinel monitoring program to better understand the distribution of koalas and also their genetics and health.

Other monitored species in north-east forests

Artificial intelligence is used to identify other key forest species recorded as a part of the koala occupancy assessments. These include the yellow-bellied glider ((Petaurus australis (see Image B2.1)), squirrel glider (Petaurus norfolcensis), powerful owl (Ninox strenua) and sooty owl (Tyto tenebricosa).

Image B2.1: Yellow-bellied glider (Petaurus australis)

Analysis of these findings is still ongoing, but results for the yellow-bellied glider (Petaurus australis) indicate that this species occupancy declined by 34% after the 2017 drought and the 2019–20 bushfires in north-east NSW. The glider was showing signs of recovery in 2020 and 2021 after drought-breaking rains () (see Figure B2.4).

Figure B2.4: Yellow-bellied glider occupancy at monitoring sites, 2015–21

Notes:

This data accounts for imperfect detection and environmental factors such as elevation at monitoring sites.

Changes in bat density

Bats make up 25% of Australia’s mammal species. They vary greatly in size, diet, behaviour and habitat.

More than 77 species are found in Australia, 34 of which live in NSW ().

Bat species contribute to the health and regeneration of Australia’s native forests by:

- transporting pollen over vast distances

- dispersing large seeds

- transferring food matter between species ().

Since 1999, the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development has done annual banding of four forest bat species in Chichester State Forest in northern NSW, which is a mountain forest climate refuge. This has allowed researchers to estimate changes in the density (number of bats per hectare) of forest bat species over time.

The species of bats monitored are the:

- large forest bat (Vespadelus darlingtonia)

- eastern forest bat (Vespadelus pumilus) (see Image B2.2)

- chocolate wattled bat (Chalinolobus morio)

- southern forest bat (Vespadelus regulus).

Image B2.2: Eastern forest bat (Vespadelus pumilus)

Analysis of estimated density of bats per hectare showed that:

- each species preferred either high or low altitudes

- bat density was higher in years with more annual rainfall

- bat density was lower in years with a higher maximum temperature.

Overall, the densities of all species were higher than previous estimations.

From 2013, there was an increase in density of the eastern forest bat despite a higher annual temperature on the site (see Figure B2.5). This is an example of a species responding to a changing climate.

Figure B2.5: Eastern forest bat (Vespadelus pumilus) density, 1999–2020

Notes:

High elevation is >600 m, and low elevation is <600 m.

Native birds

Populations of threatened and near-threatened birds across NSW and the ACT have declined by 56.3% since 2000, reflecting a pattern witnessed globally ().

Bird declines may be attributed to habitat loss (for example, from weeds, clearing and extreme natural events) and impacts of invasive species, such as rats mice and rabbits (). The creation of invasive animal-free sanctuaries can help native bird populations to recover ().

The effects of climate change also contribute to the decline, with increases in the risk of droughts, fires and heatwaves (). Heatwaves, combined with increasingly high temperatures, can be devastating to bird populations, even those adapted to hot dry environments.

For example, in 2017, scientists monitored the breeding season of a wild population of zebra finches in north western NSW. They found 95% of the eggs did not hatch. These deaths were due to the developing embryos being exposed to continued high temperatures during a multi-day heatwave ().

Some Australian bird species (14%) have declined in their distribution or become extinct in the last 200 years (see Figure B2.6). Generally, birds have been more resistant to declines than mammals.

While many species are declining in towns and cities, a few are flourishing, such as noisy miners (Manorina melanocephala) and rainbow lorikeets (Trichoglossus moluccanus) (). In some suburban and urban areas, there is moderate bird diversity.

Figure B2.6: Percentage of native bird species that have declined in the past 200 years

Notes:

Presumed extinct – 100% contraction in distribution

Severe decline – 50–<100% change in distribution

Moderate decline – 25–<50% change in distribution

No significant decline – less than 25% change in distribution

n=total number of species recorded as living in NSW at the time of European settlement. This does not include species regarded as ‘vagrants’ (occasional or accidental sightings of species well outside their normal range).

CL=confidence interval

Threatened Bird Index

The Threatened Bird Index measures changes in populations of Australia’s threatened and near-threatened bird species. The index helps scientists better monitor progress in achieving conservation targets.

Information for the Threatened Bird Index comes from government and non-government agencies, and citizen science groups.

Bird species are put into one of four groups, depending on where they live:

- marine environments

- shoreline environments

- on land and in forests

- wetlands.

Populations of threatened bird species in NSW are decreasing. This indicates a drop in bird populations across the State over time.

NSW and the ACT have had a decrease of 56.3% in bird populations since 2000. Birds on land and in forests have had the greatest decrease. This is due to habitat destruction, climate change and invasive species ().

As more data for more species is added, the index will become more accurate in depicting the populations of threatened bird species.

Figure B2.7 shows the average change in bird numbers compared with the baseline in 2000. The shaded areas show the confidence interval (the amount of uncertainty in the sample data).

Steep declines in populations occurred between 2000 and 2007, with numbers stabilising from 2007 and 2016. From 2016, a continued decline can be seen through to 2019.

Figure B2.7: Threatened Bird Index 2023, showing population trends 2000–2020 across bird species in NSW

Notes:

Threatened Bird Index for NSW is based on data provided on threatened and near-threatened bird species.

The index measures average changes in bird populations each year, which is compared to the base year (2000). This year was chosen as it is the first year that consistent data are available.

For 2000, the Index gets a score of one. The score then goes up or down in subsequent years. For example, a score of 1.2 means a 20% increase on average compared to 2000. A score of 0.8 means a 20% decrease on average compared to 2000 (Threatened Species Index n.d.).

Birds after bushfires

Bushfires are a seasonal part of Australian life and play an important ecological role. As our climate changes, there will be an increased risk of bushfires becoming more frequent, intense, severe and extensive.

See the topic for more information about bushfire risk.

The 2019–20 bushfire season was one of the most severe in recent history (), with more than 2.7 million hectares of NSW national park estate affected ().

These bushfires had a catastrophic impact on wildlife, including birds (). In the aftermath, eight bird species needed immediate management actions to help their long-term recovery and prevent their further decline (see Table B2.5). These actions included protecting unburnt areas and planting new trees to maintain food supply.

Table B2.5: NSW bird species needing immediate management actions after the 2019–20 bushfires

| Common name | Scientific name | EPBC Act listing* | NSW listing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rufous scrub-bird | Atrichornis rufescens | Endangered | Vulnerable |

| Regent honeyeater | Anthochaera phrygia | Critically endangered | Critically Endangered |

| Eastern bristlebird | Dasyornis brachypterus | Endangered | Endangered |

| Albert’s lyrebird | Menura alberti | Unlisted | Vulnerable |

| Eastern ground parrot | Pezoporus wallicus wallicus | Unlisted | Vulnerable |

| Black-faced monarch | Monarcha melanopsis | Migratory | Unlisted |

| Gang-gang cockatoo | Callocephalon fimbriatum | Endangered | Endangered |

| South-eastern glossy black cockatoo | Calyptorhynchus lathami lathami | Vulnerable | Vulnerable |

Notes:

* EPBC Act stands for Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth)

Further assessment undertaken by the Threatened Species Recovery Hub indicated that many of these species would likely have long-term decreases in their populations because of the 2019–20 bushfires.

Birds that depend on dense vegetation may disappear from burnt areas for many years until vegetation regrows. Birds not killed outright during fires are often left vulnerable, with a lack of food and shelter ().

In contrast, some bird species that prefer open habitat thrive in post-fire areas ().

Native fish

NSW has approximately 118 species of freshwater fish, of which 57 are native ().

There are 33 species listed as threatened and four species presumed extinct under the Fisheries Management Act 1994.

Since the State of the Environment 2021, there have been five new NSW fish species listed as critically endangered in the Fisheries Management Act 1994.

These are the cudgegong giant spiny crayfish (Euastacus vesper), short-tail galaxias Galaxias brevissimus and Kosciuszko galaxias (Galaxias supremus), Lord Howe abalone (Haliotis rubiginosa) and McCulloch's anemonefish (Amphiprion mccullochi). The full list is available here.

Another six species in NSW have been listed as critically endangered and 14 as endangered under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth).

There have been declines in freshwater fish communities due to:

- river regulation that restricts their habitat or makes it no longer suitable

- loss and degradation of habitat

- limited places to move to

- population fragmentation

- modification of waterways

- excessive water taken by irrigators or farmers

- over-exploitation

- invasive species competing for habitat

- climate change.

Healthy native fish populations provide many environmental, social and economic benefits. Native fish cycle nutrients, support food webs, and provide food and recreation for people through fishing.

Native fish are also important for the social and cultural wellbeing of Aboriginal peoples (). For many Aboriginal people, native fish species are their totem and considered as kin.

Fish are great indicators of wetland and river health. An abundance and diversity of species in an area is connected to good water quality and connected food webs. The presence of native fish and crustaceans is an early indicator of wetland recovery ().

Improving river ecosystems to stabilise banks, improve water quality, drive food webs and provide habitat can support healthy populations of native fish and help recover threatened species ().

Habitat essential to the survival of endangered or critically endangered species, populations of a species or ecological communities can be declared as critical habitat.

See the topic for more information about marine fish diversity and abundance.

Freshwater fish surveys

The Murray–Darling Basin is Australia’s largest and most complex river system. It starts in southern Queensland, then flows through NSW and Victoria to reach the sea south-east of Adelaide ().

The Murray–Darling Basin is home to more than 50 native freshwater fish species and up to 20 that use the estuary, of which 36% are threatened ().

Inland rivers and their fish communities can vary over short periods of time due to the influence of events such as floods. To reliably assess fish health, it is best to consider long-term trends ().

For example, the Basin Plan Environmental Outcomes Monitoring for Fish (BPEOM-Fish) surveys fish populations at 240 sites across the NSW portion of the Murray-Darling Basin at the same locations every year to create a strong long-term dataset. It provides detailed reports on current fish condition in the NSW Murray–Darling Basin.

See the topic for detailed reports on the numbers, distribution and biomass of key freshwater fish species.

Coastal fisheries surveys

The Status of Australian Fish Stocks (SAFS) reports provide an indication of population health for many recreational and commercial fish.

Combining historical fish surveys with recent surveys can help assess the changing distribution of fish populations. However, due to the limited nature of the historical surveys and inconsistent sampling over time, it is difficult to assess changes in distribution, so scientists can’t assess most species.

See the topic for more information.

Invasive species

‘Invasive species’ describes animals, plants and other organisms, such as pathogens, that are introduced to places outside their native ranges, where they spread and potentially harm local ecosystems and species (). They are also called introduced or feral species.

Invasive species can prey on native species or compete with them for food. They can alter the habitat of native species, by, for example, eating plants that native animals rely on, or spreading pathogens and disease.

Invasive species can also disrupt and degrade the cultures and practices of Aboriginal peoples. They may:

- disrupt traditional food sources

- degrade sacred sites

- alter natural ecosystems

- disrupt cultural practices and knowledge

- threaten culturally significant species and totem animals.

Across NSW, the spread and impact of many invasive species is increasing, with new threats emerging every year.

The NSW Invasive Species Plan 2023–2028 helps to:

- prevent new invasive species entering NSW

- eliminate or contain existing populations

- manage already widespread invasive species.

In NSW, many invasive species are key threatening processes. A key threatening process can harm or damage threatened species or ecological communities, or make a native species threatened ().

Key threatening processes are identified and listed under the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (). They include climate change, fire and diseases.

See the topic for more information on the ways invasive species affect native plants and ecological communities.

Invasive species on land

Invasive dogs, pigs, rabbits, foxes, goats, cats, pigs and deer are the most significant and widespread invasive animals on land in NSW ().

Predation by the European red fox (Vulpes vulpes), cats (Felis catus), pigs (Sus scrofa), deer (several species) and ship rats (Rattus rattus) are listed as key threatening processes under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. Foxes and cats are widespread throughout NSW and have contributed to the regional decline and extinction of many small to medium-sized native animals ().

The ability of cats to breed rapidly, travel great distances in search of prey and thrive in a wide range of habitats has made them a major threat to native animals, including threatened species ().

Foxes can limit the habitat choices and population sizes of native species, particularly medium-sized ground-dwelling and semi-arboreal mammals, ground-nesting birds and freshwater turtles.

Grazing, browsing, trampling and digging by introduced herbivores, including deer, rabbits, goats and horses can:

- lead to habitat degradation by increasing soil erosion

- destroy native plants

- prevent seedlings from growing

- spread weeds

- foul waterholes

- lead to a decline in native vegetation health, diversity and productivity.

Introduced herbivores can also outcompete native herbivores for resources. For example, feral goats can eat and trample on the habitat of endangered brush-tailed rock-wallabies and push them out of an area ().

While the distribution and abundance of many invasive animals can change with rainfall, especially in the rangelands, most invasive herbivores, such as rabbits, remain widespread and abundant across NSW.

Kosciuszko National Park has the largest wild horse population in NSW national parks. The October 2023 horse population survey estimated there were between 12,797 to 21,760 wild horses in the park.

The population had steadily increased over the past 20 years (), however major control operations in 2023–24 have significantly reduced numbers.

Under the Kosciuszko National Park Wild Horse Management Plan 2021, NPWS is required to maintain a population target of 3,000 wild horses in 32% of the park by mid-2027.

The distribution and numbers of all invasive deer species is increasing across NSW. Their distribution has increased from 17% in 2016 to 22% of NSW in 2020 (). In the Royal National Park, they have had a major impact on the variety and abundance of plant species ().

Invasive species also kill native animals because they are poisonous or toxic. For example, cane toads (Rhinella marina) are a threat to native animals because they are poisonous and eating them can kill most native animals.

To slow the spread of, and prevent more, cane toads in NSW, a Cane Toad Biosecurity Zone is in place. This incorporates all areas of NSW, except a small corner in the north-east where the species is locally established ().

Smaller invasive mammals, such as rats and mice, can also have an environmental impact. Invasive mice damage plants by feeding on seeds and seedlings. Invasive rats can eat seabird eggs and chicks, which is particularly devastating around seabird colonies and islands.

Introduced rats on Lord Howe Island are responsible for the extinction of five endemic bird species, at least 13 species of endemic invertebrates and two plant species.

The Lord Howe Island rodent eradication program was undertaken in 2019. The eradication has so far been successful. Strict biosecurity measures and monitoring were reactivated on the island and at shipping ports and the airport in April 2021 after a rat was seen (.).

Aquatic species

Introduced fish can threaten native fish, frogs and invertebrates by preying on them or competing with them for food and space.

Introduced trout, gambusia and carp are of particular concern. For example, predation and competition from trout has almost eradicated the critically endangered native fish, stocky galaxias (Galaxias tantangara) from Kosciuszko National Park. Predation by plague minnows seriously threatens the vulnerable green and golden bell frog (Litoria aurea) ().

Introduced carp are adaptable, can reproduce quickly and can modify environments, sometimes leading to significant declines in water quality and habitat availability for native fish. They have become a major invasive species throughout most of the Murray–Darling Basin.

These fish have large fluctuations in numbers, possibly having larger numbers during floods ().

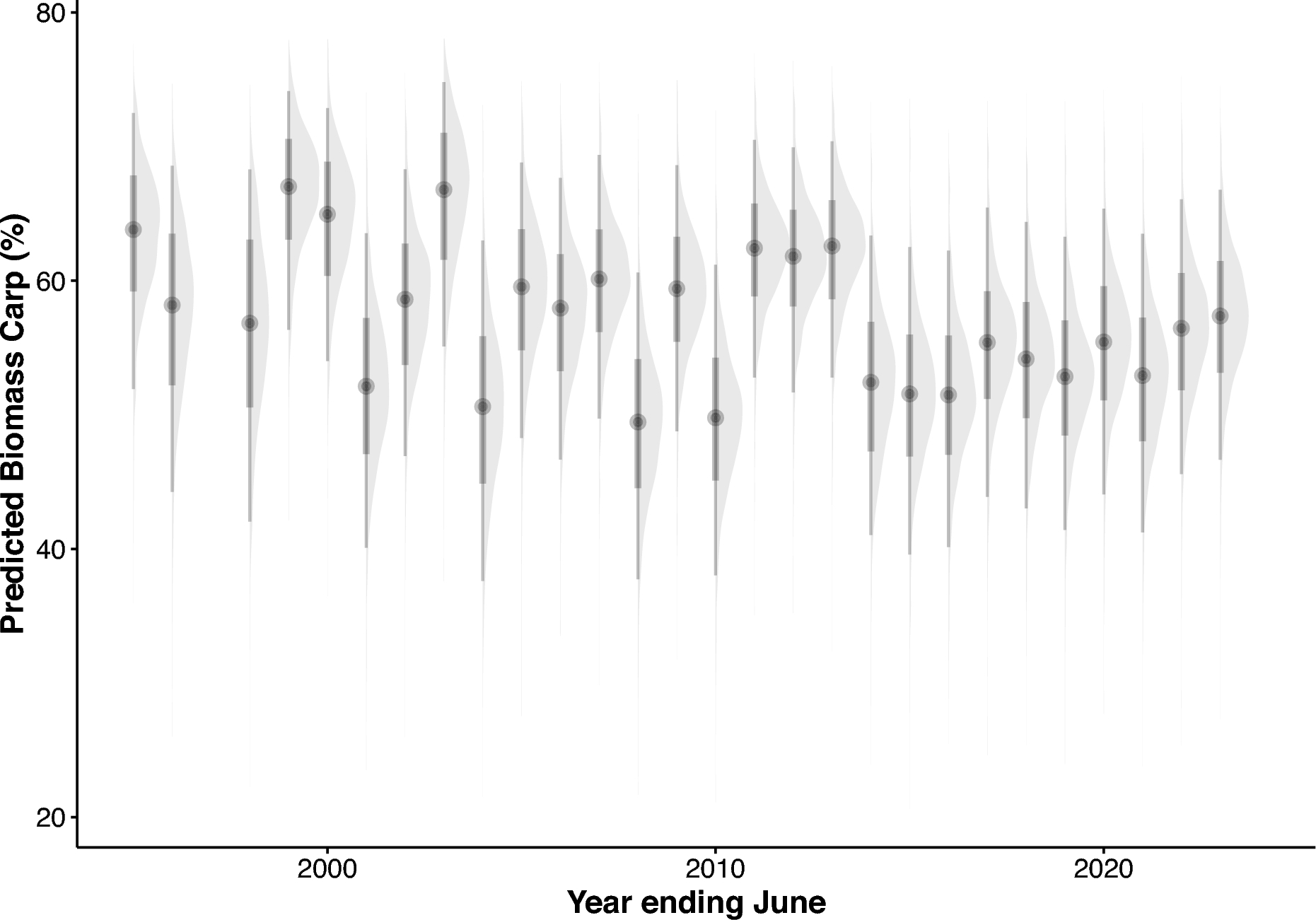

The relative proportion of carp numbers in the NSW Murray–Darling Basin has been stable at about 57% of total fish biomass since the mid-1990s. This suggests the capacity of carp to reproduce has been reached (see Figure B2.9).

Surveys of freshwater fish species in the Murray–Darling Basin between 2014–15 and 2022–23 have found that only 6% of sites were free of introduced fish. A few sites (7%) contained only introduced fish.

Most sites sampled were in the Murray–Darling Basin, which generally has fewer native fish species than coastal and other inland waterways. On all sites, introduced species accounted for 38% of fish species. For detailed reports on each NSW Murray–Darling Basin catchment, see the NSW DPIRD Murray–Darling Basin Fish monitoring reports.

Figure B2.9: Percentage of total fish biomass contributed by carp across the NSW Murray–Darling Basin

Notes:

Annual estimates of the percentage of biomass contributed by carp using data from sites across the NSW Murray–Darling Basin (elevation <700m).

The shading shows the distribution of estimates. The dots show the median estimates. Thick grey bars show the 80% credible intervals, and the thin grey bars show the 95% credible intervals.

See and for more information on carp.

Pressures and impacts

Habitat loss and fragmentation

When land is cleared of native vegetation, there is a loss of native animal species, due to their habitat being disrupted. Further disturbance follows from subsequent development and the fragmentation of remaining native vegetation.

These factors stop native plants from regenerating and native animals from moving across the landscape, leading to a loss of genetic diversity (; ).

Many insect species rely on specific habitat conditions, including old-growth mature trees, logs and fallen timber for some, or all, of their life stages. Once lost, these habitats can take decades to be replaced ().

The decline in habitat due to clearing and fragmentation is described by two Biodiversity Indicator Program indicators for habitat quality – ecological condition and ecological carrying capacity.

The level of ecological carrying capacity in 2013 was assessed at 32% of the natural levels before European settlement, and 29% in 2020 following the 2019–20 bushfires. The 2020 assessment only includes the effects of the 2019–20 bushfires. It doesn’t consider other changes in habitat or land use since 2017.

See the topic for more information about these indicators.

Urbanisation

Fragmented habitat and loss of habitat for native species are exacerbated by urban development. Impacts on native species include:

- light pollution

- noise pollution

- traffic related injuries

- invasive species.

Scientists are conducting research in NSW to understand the impacts of urban light and noise pollution on wildlife, with studies showing both can seriously harm some species.

Streetlights, headlights and security lights in towns and cities can subject nocturnal native animals to more than 1,000 times the amount of light they would naturally get from moonlight (). This increased light can:

- expose nocturnal animals to predation by invasive species such as foxes and cats

- drive native bats from roosting sites

- disrupt breeding cycles

- reduce animals’ ability to communicate, find food and travel ()

- result in shorter foraging periods so animals don’t get enough food.

Noise pollution can disrupt:

- migration paths for, and communications between, both birds and whales

- the hunting success of bats

- breeding opportunities for frogs and birds, with some species unable to find partners ().

Development often means more vehicles. There are more animals going into rescue and rehabilitation due to motor vehicle collisions every year ().

The wildlife rehabilitation data dashboard uses information from wildlife rehabilitation providers about native species that are killed or injured as a result of car strikes and domestic animal attacks in NSW.

Towns and cities also help invasive species to become established and spread (). While towns and cities have challenges for native animals, they also provide habitat for them (). It’s estimated about 30% of Australia’s threatened species listed in the Environment Protection Biodiversity and Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) live in towns and cities.

Research conducted on the distribution of threatened species finds that urban areas have more threatened species than rural areas (; ).

Urban development also damages aquatic ecosystems in a number of ways:

- land clearing, dredging and land reclamation along the NSW coast degrades estuarine ecosystems

- vegetation clearing, snag removal and bank erosion causes loss of habitat

- there’s increasing sediment, nutrient and pollution runoff

- construction of dams, weirs, floodgates and road crossings obstruct migration routes, reduce breeding opportunities and restrict native species’ ability to avoid predation ()

Urban, industrial and agricultural development have disrupted the natural environment and the freshwater environments of NSW. Native fish have seriously decreased in distribution and numbers, with nearly two-thirds of native freshwater fish listed as threatened under State or Commonwealth legislation.

See the and topics for more information.

New and emerging invasive species

Invasive species have greatly contributed to the decline and extinction of many native species and continue to impact Australia’s unique biodiversity.

Invasive insects

Red imported fire ants (Solenopsis invicta) and yellow crazy ants (Anoplolepis gracilipes) are among the top 100 invasive species worldwide. They are a potential ongoing threat in NSW ().

These are an omnivorous, opportunistic species that can form aggressive ‘super colonies’ (). They can change ecosystems by:

- outcompeting native insect species

- preying on ground-dwelling native species such as reptiles, amphibians and small mammals ()

- spraying formic acid, which is toxic to some animals ()

- eating the seeds and seedlings of native plants.

Red fire ants are known to have infested areas of south-east Queensland, close to the NSW border (). Two invasions of red fire ants were recently detected and managed in northern NSW, having spread from a larger invasion in south-east Queensland. These red fire ant infestations in NSW have not yet extended beyond Murwillumbah and Wardell ().

Two invasions of yellow crazy ants in 2018 around Lismore, in northern NSW, have been managed and surveillance is ongoing. Following an extensive surveillance and treatment program both sites remained free of yellow crazy ants until a small colony was identified in early 2021 in the Lismore CBD ().

These ants will pose a significant risk if they are not eradicated, because:

- they threaten agriculture, infrastructure, outdoor recreation and human health

- their painful stings can cause severe allergic reactions in some people

- they can prey on native plants and animals, leading to biodiversity loss.

The economic costs of managing and controlling fire ant infestations can be substantial for both the public and private sectors ().

See the Status and trends section of this topic for other invasive animals and invertebrates.

Invasive plants or weeds

Invasive plants or weeds can:

- smother or outcompete native plants, reducing the habitat for native animals

- help bushfires spread and be more intense

- have spines or thorns that can hurt native animals, or are poisonous

- form impenetrable thickets so native animals cannot reach suitable habitat

- affect soil nutrient levels, salinity and stability, leading to habitat modification and loss of food for native animals ().

For example, toxins in introduced pasture grass Phalaris aquatica can give eastern grey kangaroos the deadly disease, chronic phalaris toxicity ().

Some aquatic weeds can decrease water quality and reduce available habitat (). For example, floating weed mats formed by alligator weed (Alternanthera philoxeroides) can deprive water of oxygen and kill native fish ().

Pathogens and disease

Exotic parasites and pathogens can be introduced by invasive species. Several of these can harm native wildlife, livestock and humans.

Threatened species with reduced or restricted populations are particularly vulnerable. Even a small decrease in the numbers of these species can result in their eventual extinction ().

For example, toxoplasmosis is carried by invasive cats and Angiostrongylus cantonensis, a lung worm, is carried by introduced rats. Both these can infect native wildlife, humans and domestic animals.

Marsupials are particularly at risk from toxoplasmosis. Infection can cause paralysis, blindness, and respiratory and reproductive disorders ().

Some diseases are already harming native species.

Koalas can contract chlamydia, a common disease that can result in blindness, urinary tract infection and reduced reproductive success. The NSW Government is funding research and vaccine trials to increase koalas’ resistance to chlamydia ().

Chytridiomycosis is caused by the chytrid amphibian fungus. It is a global threat to frog populations, including in Australia where it can spread quickly and cause mass deaths.

It attacks the keratin in a frog’s skin, although the exact cause of death is still unknown (). While there is no treatment yet, the NSW Government is funding projects to find one.

Pathogens and diseases affecting plants, such as myrtle rust and phytophthora dieback, can also harm native animals, because they cause loss of habitat for native animals that rely on these plants for food and shelter.

Bird flu (Avian influenza) is an infectious disease that affects birds worldwide. Some mild strains are present in Australia but have little impact on wildlife ().

One highly infectious strain (H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4b) is different to other strains of avian influenza because it spreads rapidly in both birds and other wildlife (). Overseas, it has led to mass deaths of wild birds and mammals, particularly marine mammals (such as seals, sealions and dolphins) and mammals that prey or scavenge on birds (). This strain cannot be eradicated.

H5N1 has not been detected locally in Australia (). However, there is no way to prevent H5N1 entering Australia and the risk of it entering Australia in the future is high ().

See the Wildlife Harm Australia website for more information.

Long-term data gaps

Although knowledge of the conservation status of many species has improved markedly over the past 20 years, especially the distribution and abundance of land-based vertebrates, there is still much to learn about other groups. Many species remain poorly known or have not yet been scientifically described and named.

Recording the status of all animal species across NSW is a huge, complex task, especially when many species remain unknown. Systematic monitoring of the NSW-wide array of biodiversity is also difficult due to spatial, financial and technological limitations.

For most invertebrates, information exists for only a few isolated species, and this provides little insight into their broader status and management needs. This can lead to biases in our overall understanding of diversity, and whether species and groups are threatened.

Long-term data for insect and fungi species status and trends is almost non-existent, even though they are vital to ecosystem health.

Patterns of decline that are likely to have been present for many years are still being discovered in lesser-studied groups of animal species.

Climate change

Climate change is increasing the threats native animals face, and introducing additional pressures (; ; ).

The ability of native species to adapt and persist under climate change is limited (). The following factors are likely to decrease the resilience of species to climate change:

- less opportunity to move or extend their range due to fragmentation of habitat and isolation of populations ()

- increased risk of more frequent or intense extreme weather events, such as heatwaves, droughts, storms, floods and bushfires, pushing species outside their regular habitats.

Climate change will probably overtake habitat destruction as the greatest global threat to biodiversity over coming decades ().

In NSW, habitat loss and climate change combine to reduce the resilience of ecosystems. For example, bioregions in central NSW have historically high rates of habitat loss. They will need more active habitat management, such as restoration projects, to prevent further biodiversity loss due to climate change ().

See the topic for more information.

Extreme weather

Recent extreme weather such as the 2019–20 drought and bushfires and 2021–22 storms and floods have increased the threat to biodiversity.

Higher than average temperatures, low rainfall and dry vegetation following an extended drought from 2017 to 2020 were large contributors to the 2019–20 bushfire season ().

The length and intensity of bushfire seasons and increased number of high-risk fire weather days are also consistent with the impacts of climate change ().

The 2019–20 bushfires had a profound impact on NSW wildlife:

- 2.7 million hectares of national parks were burnt

- almost 3 billion native animals were killed or displaced

- 22% of all good to very good koala habitat in eastern NSW was burnt

- 46 threatened species had at least 90% of their habitat in burnt areas ().

Recovery will be slow for most fire-affected species. For some animals the fires have accelerated pre-existing population declines.

During the record-setting 2022 floods across north-east NSW, thousands of injured animals were taken in by wildlife hospitals and carers across the impacted region ().

See the topic for more information.

Climate change in rivers and wetlands

Climate change is predicted to have severe impacts on communities of fish and individual species, leading to local extinction and declines in species distribution in rivers and wetlands ().

Climate change is already leading to habitat and range changes such as:

- increased water temperatures that disrupt breeding and alter competition

- less native vegetation available to control erosion and filter water, disrupting and altering collaborative relationships between species

- the spread of disease

- poor fish health.

The reduced flow of rivers and streams will:

- reduce habitat quality and quantity

- limit the ability of fish to move from place to place

- restrict the movement of fish to seek suitable habitat and spawn.

See the topic for more information.

Change of range

Most rangeland habitats are becoming harder for native animals to live in, particularly when there is little water.

As the climate changes, Australia’s native animals are showing an ‘adapt, move or die’ response (). Some species have already moved, with species that depend on cooler habitats moving to higher altitudes and others extending their ranges due to warmer average temperatures.

The coastal waters of eastern Australia have seen at least 70 marine species moving south. This is due to warming temperatures and cooler ocean waters in the south.

See the topic for more information.

Birds and bats are moving more to follow food, escape competition from introduced species or move to more suitable habitats ().

The loss of canopy cover also reduces availability of shade.

See the topic for more information on canopy cover.

Responses

Strategy and policy protections

Biodiversity Conservation Act

The purpose of the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 is to maintain a healthy, productive and resilient environment for the greatest wellbeing of the community, now and into the future, consistent with the principles of ecologically sustainable development.

The Act establishes several regulatory programs and governance arrangements, including:

- the biodiversity conservation program (known as Saving our Species) for threatened species and threatened ecological communities

- the private land conservation framework, and requirements to develop a Biodiversity Conservation Investment Strategy and a biodiversity values map

- the Biodiversity Offsets Scheme and Biodiversity Conservation Fund

- the Biodiversity Conservation Trust

- compliance frameworks – including for licensing, conservation, listing of threatened plants and animals, assessment requirements for planning activities and land certification

- scientific and other advisory committees.

An independent review of the Act found that it did not meet its purpose of maintaining a healthy, productive and resilient environment. It recommended a number of reforms.

NSW plan for nature

NSW plan for nature, released in July 2024, is the State Government’s response to the recommendations made in reviews of the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 and the native vegetation provisions of the Local Land Services Act 2013.

The response acknowledges that biodiversity in NSW is in crisis and that the Government’s policy objective needs to shift from mitigating decline to restoration and repair. This is essential to the wellbeing and prosperity of current and future generations.

Priority actions include:

- strengthening the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016

- exploring, in partnership with Aboriginal stakeholders, new and better ways to support Aboriginal people to connect with and care for Country

- developing a NSW nature strategy

- improving whole-of-government accountability for biodiversity outcomes

- better incorporating biodiversity into strategic planning processes

- reforming the Biodiversity Offsets Scheme

- improving biodiversity data, tools and reporting

- improving the regulation of native vegetation in rural areas

- commissioning independent advice on options to improve biodiversity outcomes in regional landscapes, and enhance value and support for landholders.

Threatened Species (Zero Extinctions) Framework

The NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) has adopted a zero-extinction target for threatened species on land managed by the agency. Actions to support this target and restore populations of threatened species are set out in the Threatened Species Framework.

The first report published under the framework was released in September 2024. It includes an overview of relevant programs and initiatives, and highlights achievements during 2021–22 and 2022–23.

Australia’s Strategy for Nature 2024–2030

A National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, titled Australia’s Strategy for Nature 2024–2030, is a collaboration between state and federal governments. The strategy aims to halt and reverse biodiversity loss in Australia by 2030.

Threatened Species Action Plan 2022–32

The Australian Government’s updated Threatened Species Action Plan 2022–32 lays out actions to protect, manage and restore Australia’s threatened species and important natural places.

Basin Plan and water sharing plans

The Basin Plan sets the amount of water that can be taken from the Murray–Darling Basin each year, while leaving enough for our rivers, lakes and wetlands and the plants and animals that depend on them.

Water sharing plans protect environmental health of water and ensure it is sustainable, by showing when and how water will be available for extraction.

Improved water management under the Basin Plan and water sharing plans will help recover threatened fish populations, by increasing water flows on floodplains and habitats.

Assets of intergenerational significance

Assets of intergenerational significance are areas of land within NSW declared under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 as having exceptional environmental or cultural value. Once land has been declared as an asset of intergenerational significance, it cannot be interfered with, damaged, harmed or disturbed.

As at November 2024, there were 279 areas declared as an asset of intergenerational significance. These include habitats for the Wollemi pine, koalas and the greater bilby.

Conservation programs

NSW Koala Strategy

The NSW Koala Strategy 2021–26 supports investment in koala protection and conservation actions.

In 2022–23, as part of this strategy, 5,885 hectares of koala habitat had been restored or were in the process of being restored.

The NSW Government is reviewing the strategy to identify future conservation priorities and ensure the long-term survival of koalas in the wild.

In March 2024, 140 stakeholders from across NSW met at Taronga Zoo for the NSW Koala Summit to discuss the effectiveness of koala conservation efforts and make recommendations to shape the future of the strategy. This was a key point in the strategy review ().

Feedback from the discussion paper and the NSW Koala Summit will also inform the review.

Find out more about actions to protect koalas.

Saving our Species

Legislated under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, the Saving our Species program aims to secure threatened species in the wild and control key threats. It delivers conservation strategies and supports actions that can help save threatened plants and animals from extinction.

Since the program began in 2013, it has worked in partnership with more than 300 community and government organisations, universities, researchers and the business sector to maximise investment and strengthen conservation actions.

More than 170 species that Saving our Species invested in during 2023–24 are on track to be secure in the wild in NSW for 100 years.

During 2023–24, Saving our Species delivered actions across more than 300 projects for threatened plants, animals and ecological communities and key threatening processes at more than 690 sites across NSW.

Some actions taken through Saving our Species in 2023–24 were:

- using aerial surveys to find eight new colonies of the threatened brush-tailed rock-wallaby in Kangaroo Valley

- using DNA analysis to identify prey species in predator scats

- using traditional knowledge from Aboriginal people – this information helped identify which introduced and threatened native animals lived in an area and create actions to control the predators.

Bushfire science

While some native animals cannot survive intense fires, others need it to thrive. As bushfires are increasing in intensity and frequency, the NSW Government has implemented the Applied Bushfire Science Program to:

- improve understanding of how bushfires affect native plants and animals

- improve clarity of information provided to fire managers so they can make better decisions

- integrate cultural and environmental knowledge into bushfire risk management and planning.

Aquatic habitat mapping

The Aquatic Habitat Mapping Program:

- develops riverine mapping projects to identify instream and riparian habitats

- provides information to assess environmental impacts

- introduces restoration and rehabilitation actions to improve aquatic environments and manage river flows.

See fish and flows for more information.

The Fisheries Threatened Species Captive Breeding & Conservation Stocking program increases numbers of threatened fish species through genetic rescue and breeding.

Between 2020 and 2023, 13 threatened fish species were bred in captivity. More than 375,000 fish were released into suitable habitats in rivers and streams.

See fish stocking for more information.

WildCount

WildCount was the NPWS long-term animal monitoring program.

From 2012 to 2022, motion-sensitive digital cameras were used at 200 sites, in 146 NSW parks and reserves, to track changes in wildlife sightings. The data was used to:

- identify changes in occupancy to understand if animals are in decline, increasing or stable

- guide conservation actions

- work out whether changes in animal populations could be related to factors such as climate change, seasonal weather and bushfires.

For example, WildCount has extensive data for 200 sites before the 2019–20 bushfires. Seventy sites were burnt during the bushfires. Information from these sites can help scientists understand the impacts of bushfires on native wildlife and how they recover after fire ().

Broadscale monitoring also enables:

- new records of threatened species to be detected

- species to be found outside their known ranges

- the ability to detect changes in distribution of invasive species, such as foxes and rabbits.

The final WildCount report, including the monitoring results from the second half of the program from 2017 to 2022, is being finalised. It should be available in early 2025.

Ecological health scorecards

The ecological health performance scorecards program is a biodiversity monitoring program led by the NPWS.

The pilot program measures the health of our national parks in eight sites across NSW by monitoring environmental indicators related to:

- the health of native plants and animals

- threats to ecological health, such as invasive animals and weeds

- important ecological processes, such as soil chemistry and water quality

- fire patterns.

Each site represents a major ecosystem within the national park estate. Most of the scorecards should become available in 2025.

Invasive animal control

Lord Howe Island

The Lord Howe Island Rodent Eradication Project has succeeded in removing the ship rat (Rattus rattus) and house mouse (Mus musculus) from Lord Howe Island, nearby islands and rocky islets.

Wiping out these rodents has benefited biodiversity and many native plants and animals, including the endangered Lord Howe Island woodhen. It has also meant critically endangered species can be reintroduced, such as the Lord Howe Island stick insect (). No rats were found on the island between 2021 and 2023 ().

National parks

Invasive animals threaten biodiversity across NSW national parks and can also cause damage to areas that are culturally and historically important, such as Aboriginal rock art sites.

Working together with similar agencies, the NPWS manages programs that tackle these threats. The NPWS has developed specific regional pest management strategies, which are used to guide and implement best practice control and monitoring programs in national parks and reserves.

The NPWS has been delivering record levels of invasive animal control since 2019–20, including the largest aerial shooting program in its history.

The NPWS aerial shooting and baiting programs have been increasing since January 2020 to address invasive animals including foxes, feral cats, wild dogs, goats, pigs, wild horses and deer. These efforts:

- mean there is more habitat and food for native animals

- prevent the spread of diseases brought in by introduced animals that native animals have no resistance to

- protect threatened species, native plants, animals, landscapes and catchment values

- limit the impact on neighbouring properties.

In addition, NPWS has commenced an $8.5 million targeted feral cat control initiative focused on strategic feral cat control and monitoring over three years. The initiative includes a dedicated feral cat ground shooting team that will also work to establish an effective toxic bait for feral cats in NSW ().

Private land

Local Land Services coordinates nil tenure, collaborative invasive animal control programs, with a focus on private land.

A nil tenure approach means that responsibility, control activity and cost for invasive animal management is shared across private and public land managers to fix a common problem.

Local Land Services also gives land managers tools, programs, support, training and advice to help them control invasive species on their land.

Carp

Released in 2022, the National Carp Control Plan uses a virus to kill introduced carp. Scientists are determining if the virus is safe, effective and feasible so it can be released in waterways where carp live.

Feral predator-free areas

The NPWS is establishing a network of predator-free areas within NSW national parks. At the time of writing, the network contains 10 sites where locally extinct and threatened native mammals are being reintroduced and ecosystem functions are being restored.

This will eventually create 65,000 hectares of land where threatened animals can survive.

More than 50 threatened and locally extinct animals will benefit from the exclusion of these predators. Some threatened species, including bilbies, numbats and golden bandicoots, have already been released on three of the sites.

Restoration and rehabilitation

Biodiversity Offsets Scheme

Legislated under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, the Biodiversity Offsets Scheme provides a mechanism to avoid, minimise and offset the impacts of development and some types of clearing on biodiversity in NSW.

As at 30 September 2023, the scheme had:

- protected 64,889 hectares through land management under Biodiversity Stewardship Agreements

- invested $288 million in the Biodiversity Stewardship Payment Fund for managing Biodiversity Stewardship Agreement sites

- paid nearly $15 million from the Biodiversity Stewardship Payment Fund to generate biodiversity gains through weed and invasive species management, fire management and land restoration works

- established a $106 million Biodiversity Credits Supply Fund to supply biodiversity credits.

Habitat restoration

Local Land Services is delivering 17 projects across NSW as part of the National Landcare Program. This program helps threatened birds, such as the mallee fowl, plains-wanderer, swift parrot and regent honeyeater.

In 2022–23, Local Land Services:

- restored 10,500 hectares of mallee fowl habitat

- restored 4,914 hectares of plains-wanderer habitat

- protected 1,129 hectares of native habitat to support swift parrot recovery.

Wildlife rescue

Volunteers in wildlife rehabilitation rescue more than 100,000 sick, injured and orphaned native animals every year. They represent about 500 different species.