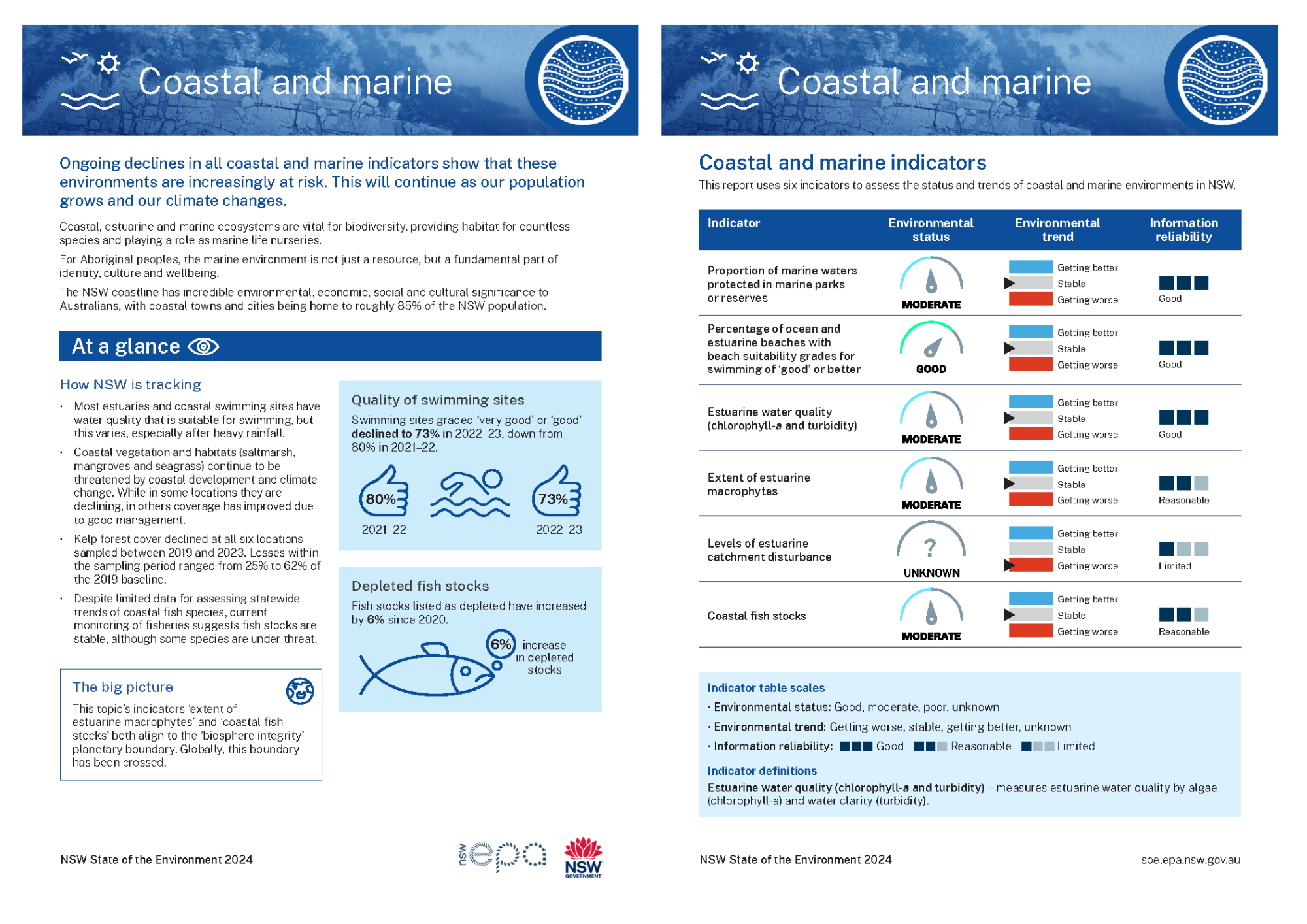

Topic report card

Read a two-page summary of the Coastal and marine topic (PDF 243KB).

Overview

NSW has about 1,750 kilometres (km) of coastline, 826 beaches and 185 estuaries and coastal lakes ().

Coastal and marine environments provide important habitats for animals and plants, as well as places for recreation and fishing.

For Aboriginal peoples, the marine environment is not just a resource, but a fundamental part of identity, culture and wellbeing.

As our population grows and our climate changes, coastal and marine environments are coming under increasing risk.

Condition

The area of NSW marine protected areas has remained stable at 35% of the NSW marine estate.

The proportion of marine and estuarine beaches suitable and useful for swimming declined: 73% of the 225 monitored sites were rated as very good or good in 2022–23, a decline from the previous year’s 80%.

The water quality of NSW estuaries has remained stable in recent years. Data on estuarine turbidity and chlorophyll-a from July 2007 to April 2024 rated the water quality of 66% of estuaries as good.

The extent of estuarine macrophytes (large aquatic plants) in NSW showed an overall increase in mangrove area but a decrease in saltmarsh area. Change in area varied among the 18 estuaries that were remapped in the past 3 years. Over these estuaries, mangrove area increased by 624ha (12%), but saltmarsh decreased by 76ha (4%).

Fifteen of the 18 remapped estuaries reported an increase in mangrove area. Eight reported a decrease in saltmarsh area.

Estuarine catchments have become more susceptible to external factors in recent years, with 94 of the 184 estuaries identified as vulnerable.

The overall relative abundance of fish species along the NSW coast was also relatively stable. Fish abundance declined in 2011 but reached newly observed highs in 2022.

Why our coasts are important

Coastal ecosystems have long been deeply treasured by human cultures and societies. We have, and still do, live, swim, fish, farm, trade, celebrate and camp all along our coasts.

These ecosystems are formed by a combination of terrestrial (land), freshwater and marine (sea) processes and contain unique habitats and species, and comprise beaches, bays, estuaries, harbours, islands, sand dunes, coastal floodplains and wetlands.

For millennia, the marine environment has been deeply connected to the lives of Aboriginal peoples (). The cultural significance of the ocean in Aboriginal cultures is evident in stories, songlines and spiritual beliefs interconnected with the marine environment (). Middens – mounds of shell and bone remains – are evidence of the long history of Aboriginal peoples’ relationship with the marine environment ().

The coastal, estuarine and marine waters of NSW contain high biodiversity (variety of animal and plant species) owing to their diverse range of habitats and the influence of subtropical and temperate ocean currents.

These varied environments:

- prevent coastal and seabed erosion

- maintain coastal water quality and healthy aquatic ecosystems

- act as key habitats for fish and other marine life

- provide recreation, visual amenity and food production.

The health of coastal and nearshore marine environments is closely linked to the health and activities of coastal river catchments, the flow of water through these catchments and marine processes.

The health of and access to our coastal environments are fundamental to human health and wellbeing, particularly for Aboriginal peoples (; ; ; ).

There is no separation between the land and sea for Aboriginal peoples, the health of the marine environment is intrinsically tied to the wellbeing of the land and all living things (). This deep connection forms a sense of identity for coastal Aboriginal communities. The ocean contributes to their physical and mental health through sustenance, cultural practices and the connection it provides to their ancestral lands (). Ultimately, the marine environment is not just a resource for Aboriginal peoples, but a fundamental part of their identity, culture and wellbeing.

Find out why coastal environments are important to the Yuin people.

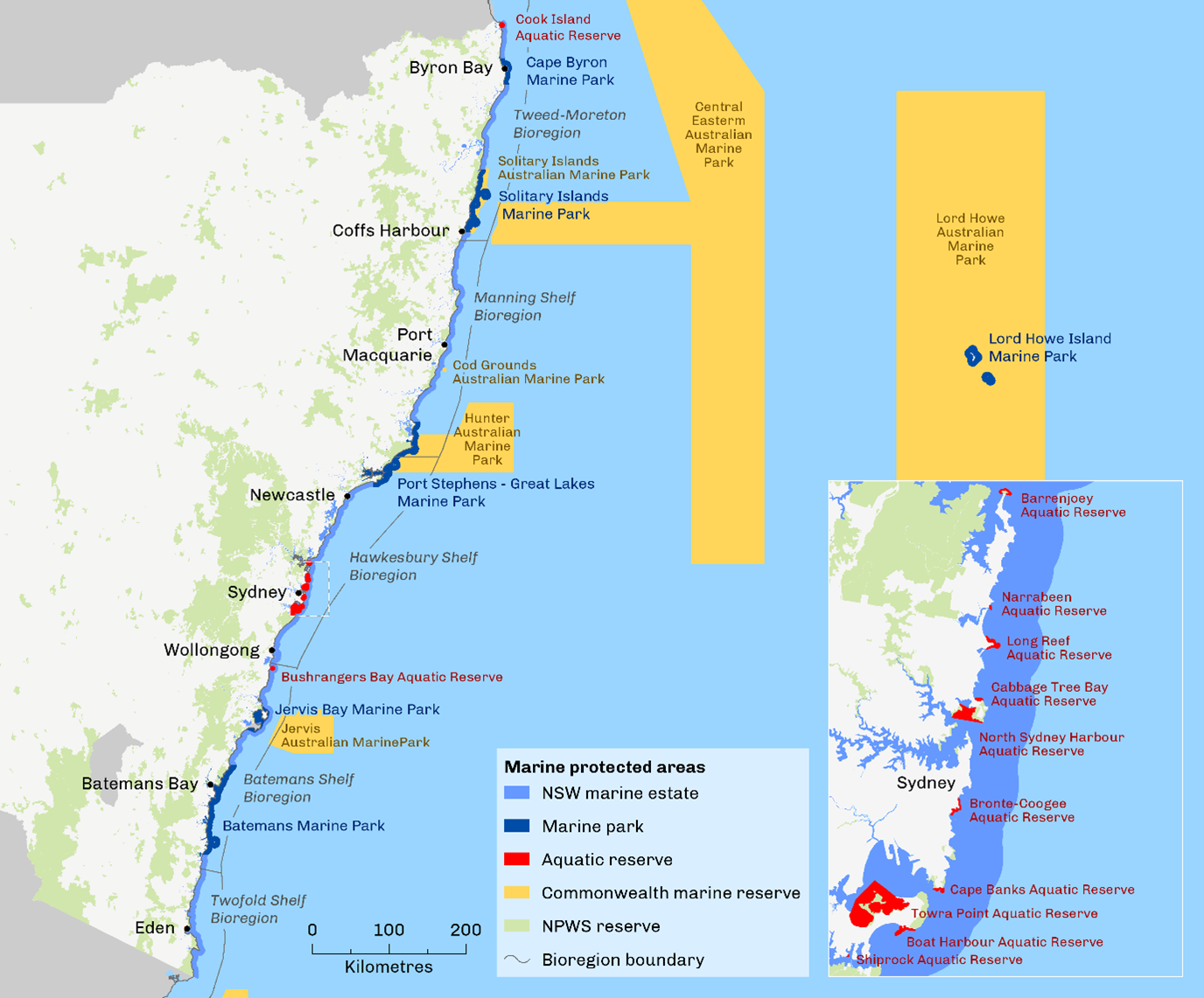

NSW marine estate

The NSW marine estate covers the ocean and coastal areas of NSW, along with their natural resources and ecosystems.

Resources and ecosystems include marine biodiversity, fishery resources, coral reefs and seagrass beds, as well as economic, cultural and environmental values ().

The NSW marine estate extends from the Queensland border to the Victorian border and encompasses:

- the ocean – out to three nautical miles (5.46km) from the mainland coast and around islands such as Lord Howe and the Solitary Islands

- estuaries – to the tidal limit (where the high tide reaches upstream)

- the coastline – beaches, dunes and headlands

- coastal wetlands – saltmarsh, mangroves and seagrass beds

- coastal lakes and lagoons connected to the ocean.

The NSW marine estate can be divided into six marine bioregions (see Map W3.1). Each of these bioregions is ecologically distinct, with different temperature conditions, habitat types and resident species.

Five of these bioregions are adjacent to the coast and one surrounds Lord Howe Island.

Map W3.1: Marine parks and aquatic reserves along the NSW coast

Threats to the NSW marine estate

Much of the NSW coastline is highly populated.

The activities that occur in coastal catchments and the marine estate put significant pressure on the health of our coasts and nearshore marine waters. A statewide threat and risk assessment identified the priority threats to the health of the coast, estuaries, marine waters and local culture ().

The top ten environmental threats and risks are:

- urban stormwater discharge

- estuary entrance modifications

- diffuse-source agricultural runoff (in estuaries)

- clearing of riparian (riverside) vegetation along waterways and adjacent habitat, including wetland drainage

- climate change stressors (sea level rise, land and sea surface temperature increases, altered ocean currents and nutrient inputs)

- modified freshwater flows (in estuaries)

- foreshore development

- boating infrastructure and recreational and tourism boating (in estuaries)

- navigation and entrance management, navigation and entrance modification and harbour maintenance (in estuaries)

- sewage effluent and septic runoff.

The greatest threats to the social, cultural and economic benefits were primarily associated with:

- water pollution

- limited social, cultural and economic information

- lack of compliance with regulations

- lack of access to the marine estate.

Estuaries are at higher risk than the coast and ocean, mainly due to their high level of use and lower resilience to threats. Marine invasive species are also an issue along the NSW coast, outcompeting native species and degrading habitats.

Coastal development has also damaged Aboriginal cultural sites and restricted access to important places and animals and plants used for food and medicine.

Management of the NSW coast

Rehabilitation and protection will improve our coastal and estuarine environments.

Actions include adaptation to the effects of climate change – such as sea level rise and increases in sea surface temperatures – and building resilience to potential extreme weather events, such as storms and cyclones.

NSW has a suite of management frameworks and legislation to manage the marine estate. These encompass objectives for coastal management, coastal land use planning, environment protection, and the conservation and management of fisheries and aquatic ecosystems.

Key strategies include:

- the Marine Estate Management Strategy

- the Marine Water Quality Objectives for NSW Ocean Waters

- the Risk-based Frameworks for Considering Waterway Health Outcomes in Strategic Land-use Planning Decisions

- Coastal Management Plans

- NSW State Environmental Planning Policies.

Table W3.1 lists current legislation and policies that support the management of our coast and marine ecosystems.

Table W3.1: Current legislation and policies relevant to coastal and marine ecosystems

| Legislation or policy | Summary |

|---|---|

| Coastal Management Act 2016 | Establishes the coastal zone and objectives to manage the use and development of the coastal environment in an ecologically sustainable way. |

| Fisheries Management Act 1994 | Legislates the management of fishery resources and their habitats in New South Wales. It also legislates that the fishing needs and traditions of Aboriginal people are appropriately considered in the management of fisheries resources. |

| Marine Estate Management Act 2014 (MEM Act) | Provides for the strategic and integrated management of the whole marine estate – marine waters, coast and estuaries – consistent with the principles of ecologically sustainable development. It also provides for the management of marine parks and aquatic reserves. |

| NSW Marine Estate Management Strategy 2018–28 | Outlines how the NSW Government will address priority statewide threats to the marine estate, such as climate change, water quality and pollution, and protection of threatened and protected species. See the Responses section of this topic for more information. |

| State Environmental Planning Policy (Resilience and Hazards) 2021 | Promotes an integrated and coordinated approach to land use planning for the coastal zone, consistent with objectives of the Coastal Management Act 2016. |

Notes:

See the Responses section for more information about how coastal and marine ecosystems are managed in NSW.

Related topics: | | | | |

Status and trends

Coastal and marine indicators

This report uses six indicators to assess the status and trends of coastal and marine environments in NSW (see Table W3.2):

- Proportion of marine waters protected in marine parks or reserves measures the area of the marine parks and reserves in NSW. Since 2018, there have been no changes to the area of marine parks and aquatic reserves. They are 35% of the NSW marine estate. This indicator is assessed as moderate (see Marine parks and reserves).

- Percentage of ocean and estuarine beaches with beach suitability grades for swimming of good or better assessed as good, because 73% of the 225 monitored sites were rated as very good or good for swimming in 2022–23 (see Swimming sites).

- Estuarine water quality (chlorophyll-a and turbidity) measures estuarine water quality. Based on data from July 2007 to April 2024, the water quality in 66% of NSW estuaries was rated as good. The indicator is assessed as moderate (see Estuarine water quality).

- Extent of estuarine macrophytes (including seagrasses) is assessed as moderate, because 39% of remapped saltmarsh habitats in NSW estuaries have lost areas of saltmarsh since the 2000s, while 71% have seen an increase in mangroves areas. Several species of seagrass are less abundant (see Estuarine macrophytes and Subtidal habitats).

This indicator aligns to the ‘biosphere integrity’ planetary boundary. Globally, this boundary has been crossed (see ). - Levels of estuarine catchment disturbance status is unknown, but it is getting worse. In the last major statewide study of catchment disturbance in 2017, 94 of the 184 estuarine catchments in NSW were identified as vulnerable. It is likely that the proportion has increased with urban and agricultural development in the past seven years (see Catchment disturbance).

- Coastal fish stocks measures coastal fish community health using different metrics, such as fish diversity, abundance and fisheries stocks, in three coastal regions of NSW. From 2010 to 2022, both coastal fish diversity and abundance have remained stable. This indicator is assessed as moderate (see Coastal fish communities).

This indicator aligns to the ‘biosphere integrity’ planetary boundary. Globally, this boundary has been crossed (see ).

Table W3.2: Coastal and marine indicators

| Indicator | Environmental status | Environmental trend | Information reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of marine waters protected in marine parks or reserves | Stable | Good | |

| Percentage of ocean and estuarine beaches with beach suitability grades for swimming of good or better | Stable | Good | |

| Estuarine water quality (chlorophyll-a and turbidity)* | Stable | Good | |

| Extent of estuarine macrophytes | Stable** | Reasonable | |

| Levels of estuarine catchment disturbance | Getting worse | Limited | |

| Coastal fish stocks | Stable | Reasonable |

Notes:

*Water quality by algae (chlorophyll-a) and water clarity (turbidity)

**Stable reflects a variable result with extent decreasing in some areas and increasing in others

Indicator table scales:

- Environmental status: Good, moderate, poor, unknown

- Environmental trend: Getting better, stable, getting worse

- Information reliability: Good, reasonable, limited.

See Indicator guide to learn how terms and symbols are defined.

See the page for more information about how indicators align.

Marine parks and reserves

The network of marine protected areas shown in Map W3.1 includes:

- six multiple-use marine parks, which cover about 35% (about 345,000 hectares) of the NSW marine estate

- 12 aquatic reserves covering about 2,000 hectares of the estate

- national park and nature reserve areas below the high tide level, accounting for about 20,000 hectares of the estate.

There have been no increases to the area of marine parks and aquatic reserves in NSW since the State of the Environment 2021.

The total area of sanctuary zones, the highest level of protection for marine life and habitats, is about 65,630 hectares, or about 6.5% of the total marine estate.

These parks and reserves aim to conserve biodiversity and maintain ecosystem integrity and function (see Map W3.1).

Marine parks and aquatic reserves provide additional legislative protections to those in place for the broader NSW marine estate.

Secondary purposes of marine parks and aquatic reserves include other community benefits, such as:

- recreation and enjoyment

- Aboriginal cultural uses

- ecologically sustainable resource use

- conservation, research and education.

Indigenous Protected Areas

Aboriginal peoples have a deep connection to Australia’s coastal and marine environments. However, their involvement in marine governance remains limited ().

One Indigenous Protected Area project is designated on the NSW coast: Ngiyambandigay Gaagal (), near Coffs Harbour.

Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) are voluntary, non-legal agreements between the Australian Government and traditional owners. They are facilitated by an international framework for managing protected areas, which allows IPA designation on Indigenous-owned lands and other tenures, including Sea Country.

The program is funded by the Australian Government and is a crucial part of Australia’s National Reserve System. This system includes all formally recognized parks, reserves and protected areas across the country.

While IPAs represent a positive step forward, the number of coastal and marine IPAs is small, and Aboriginal people have minimal formal roles in managing Marine Protected Areas (; ). Despite holding invaluable Traditional Knowledge, its integration into broader marine management strategies remains insufficient ().

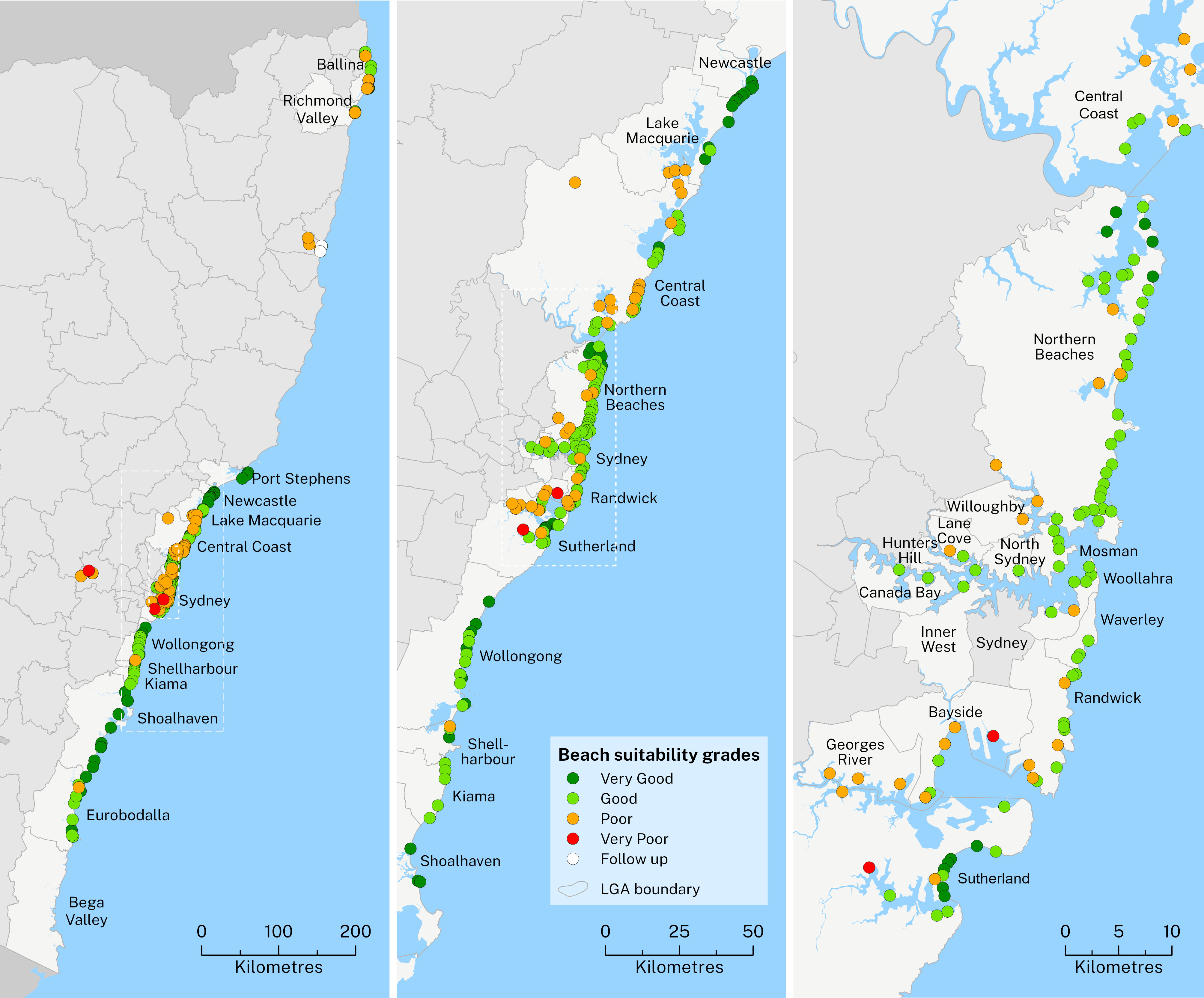

Swimming sites

The NSW Government’s Beachwatch program monitors 240 swimming sites at ocean beaches and in estuarine areas, lakes, lagoons, freshwater swimming sites and ocean baths.

Swimming sites in NSW are assigned a suitability grade, ranging from very good to very poor. Grades relate to the Microbial Assessment Category, which detects levels of enterococcal bacteria in the water to assess the risk of illness, determined in accordance with the Guidelines for Managing Risks in Recreational Water ().

In 2022, the program expanded to include some inland waterways and freshwater swimming sites (for example, Penrith Lakes).

While coastal swimming sites continue to achieve high ratings, freshwater sites and lagoons perform poorly (see Map W3.2).

See the Beachwatch website for live water quality maps.

Map W3.2: Swimming site suitability grades

In 2022–23, 73% (165 of 225) of NSW swimming sites monitored were graded as very good or good overall. This is a decline from 80% in 2021–22.

The decline reflects changes in water quality over time. It may also be influenced by changes in the number of sites monitored each year.

All ocean baths and 96% of ocean beaches achieved very good or good ratings in 2022–23.

About 56% of estuarine swimming sites achieved these ratings in 2022–23, a significant decline from 65% in 2021–22. Only 6% of lakes and lagoons were rated as very good or good. There is currently no comparative data for these sites as they were added to the program in 2022.

Rainfall is a major driver of pollution to waterways through stormwater runoff.

Untreated discharges from the wastewater treatment and transport systems can occasionally also pollute waterways if sewerage systems are overwhelmed during extreme rainfall.

Estuarine water quality

Estuarine water quality has been relatively stable overall since the State of the Environment 2021.

The NSW Government’s Estuary monitoring program monitors water quality in 164 estuaries. The program takes three years to complete. The results of the chlorophyll-a and turbidity levels are combined into an overall score from A (good) to E (poor) for each estuary in each year () presented in Map W3.3.

The extent of algae (chlorophyll-a) and water clarity (turbidity) in estuaries provides a good indication of the water quality of the ecosystem and therefore its overall health.

In NSW in 2021–23:

- 66% of estuaries were graded as good (27% Grade A, 39% Grade B), down from 71% in 2016–21

- 23% of estuaries were graded as fair (23% Grade C), up from 19% in 2016–21

- 11% of estuaries were graded as poor (10% Grade D and 1% Grade E), up from 10% in 2016–21.

See the Real-time water quality monitoring website for water quality in your area.

Map W3.3: Estuarine water quality gradings, 2021–23

Notes:

Open this interactive map in a standalone browser.

Statewide monitoring of estuaries is completed over a 3-year cycle.

Some estuaries continue to be graded as poor or very poor owing to impacts of significant urban development nearby. These include the estuaries of the Hunter River, Terrigal Lagoon, Avoca Lake, Manly Lagoon, Parramatta River, Cooks River, Towradgi Creek and Fairy Creek.

Find out about estuarine water quality in your area.

Estuarine macrophytes

Estuarine macrophytes are the aquatic plants of coastal rivers, including mangroves, saltmarshes, seagrasses and kelp.

They are key components of estuarine systems and provide a range of ecosystem services, including habitat, food, sediment stabilisation and water quality.

The NSW Department of Primary Industry and Regional Development (DPIRD) Marine Estate Management Strategy maps estuarine macrophytes on a rolling cycle using high-resolution aerial images, remapping most estuaries every five to ten years.

This report includes only 18 of the 184 estuaries, those remapped between 2021 and 2024 (the period of this State of the Environment 2024).

Changes in the extent of each macrophyte habitat in those 18 estuaries are presented below for mangroves (see Figure W3.1), saltmarsh (see Figure W3.2) and seagrasses (see Figure W3.3).

Maps of estuarine macrophytes for all available years (including the original mapping project from the 1980s) can be viewed on the DPIRD Fisheries Estuarine Habitat Dashboard.

Intertidal habitats

Mangroves

Mangroves in NSW are dominated by two species:

- Avicennia marina (grey or white mangrove)

- Aegiceras corniculatum (black mangrove).

Mangroves have been mapped in 86 NSW estuaries since the 1980s and remapped in 18 of these since 2020 (see Figure W3.1). Of these 18 estuaries, 14 have shown an increase in mangrove area since they were last mapped and three have shown a decline.

The largest increases in area occurred in the Hunter and Macleay rivers and in Batemans Bay, and the largest increases in percentage occurred in Twofold Bay, Merimbula Lake and Mooball Creek.

In the remapped estuaries, mangroves increased in area by 624 hectares.

Figure W3.1a: Mangrove area (ha) in NSW estuaries remapped within the past three years

Notes:

Only estuaries remapped since 2020 are presented.

Data from tributaries of Batemans Bay are amalgamated here.

Figure W3.1b: Mangrove area (ha) in NSW estuaries remapped within the past three years

Notes:

Only estuaries remapped since 2020 are presented.

Figure W3.1c: Mangrove area (ha) in NSW estuaries remapped within the past three years

Notes:

Only estuaries remapped since 2020 are presented.

Data from tributaries of Twofold Bay are amalgamated here.

Saltmarsh

NSW saltmarsh includes three major species:

- Sarcocornia quinqueflora (samphire)

- Suaeda australis (seablite)

- Sporobolus virginicus and Paspalum vaginatum (salt-couch).

Of the 18 estuaries mapped in this reporting period, eight show a decline in areas of saltmarsh since the 2000s, two rated moderate to severe (>20% loss), including:

- a substantial decline in the Tweed River (45% loss), some related to residential development around Terranora Broadwater and mangrove encroachment

- declines in Lake Macquarie (28%), Macleay River (16%), the Hawkesbury River (14%) and Merimbula Lake (12%)

- a decline in the Hunter River (6%) despite major restoration activities ().

Saltmarsh has increased in Cudgen Creek (86% gain) and Mooball Creek (70%), and in Twofold Bay (65%) and South West Rocks Creek (56%) potentially driven by intermittent opening and closing of the river mouths.

In the 18 remapped estuaries, saltmarsh area decreased by 76 hectares.

Figure W3.2a: Saltmarsh area (ha) in NSW estuaries remapped within the past three years

Notes:

Only estuaries remapped since 2020 are presented.

Figure W3.2b Saltmarsh area (ha) in NSW estuaries remapped within the past three years

Notes:

Only estuaries remapped since 2020 are presented.

Data from tributaries of Twofold Bay have been amalgamated here.

Figure W3.2c Saltmarsh area (ha) in NSW estuaries remapped within the past three years

Notes:

Only estuaries remapped since 2020 are presented.

Figure W3.2d Saltmarsh area (ha) in NSW estuaries remapped within the past three years

Notes:

Only estuaries remapped since 2020 are presented.

Data from tributaries of Batemans Bay have been amalgamated here.

Drivers of intertidal habitat change

Causes of saltmarsh and mangrove losses include (; ):

- urban development

- flooding and the opening or closing of lagoons

- pollution

- damage from offroad vehicles

- sea level rise.

Fluctuations in saltmarsh and mangrove coverage are common in intermittently opened lakes and lagoons because the extent of opening affects inundation of wetlands (). For example, changes in saltmarsh and mangroves declined in 2020 in Cabbage Tree Basin, in Port Hacking, apparently owing to freshwater inundation related to the closure of the narrow entrance at Deeban Spit ().

Mangrove encroachment is also a contributor to declines in saltmarsh in many estuaries (; ). This may be due to a variety of reasons, including landward encroachment associated with sea level rise (; ). Mangroves have encroached into saltmarshes at various sites in Port Hacking and in the Hunter River, the latter being the only central region estuary to show moderate mangrove increases since the 2000s (see Figure W3.2).

Large areas of saltmarsh and mangrove were also burnt in the 2019–20 Black Summer bushfires, reducing coverage in some places. Signs of recovery are present in saltmarsh but not mangroves ().

Subtidal habitats

Soft Corals

Aggregations of cauliflower soft corals form habitat for a large range of marine species. Extreme weather events, such as floods, are becoming more frequent and pose a substantial threat to nearshore marine communities.

The reduction in salinity associated with these events has substantially impacted shallow reef communities, including an endangered soft coral species, Dendronephthya australis, endemic to the south-east coast of Australia. Large volumes of freshwater ingress to marine systems through successive flood events between 2021 and 2022 has caused a major decline in the areal extent of cauliflower soft coral to the point of localised extinction in the Port Stephens estuary.

Before the floods, aggregations of colonies were persisting, and individuals were growing at two of the four monitored sites in the estuary. However, flooding in March 2021 caused a 91% decline in the remaining areal extent of D. australis.

Seagrasses are marine plants that occur predominantly in subtidal (permanently submerged) sand or mud. They provide habitats and nursery grounds for many marine animals and act as substrate and sediment stabilisers ().

Many of the seagrass species in NSW are transient. In contrast, Posidonia australis (strapweed) typically forms relatively stable meadows when not subjected to human impacts (). It occurs in 17 estuaries from Wallis Lake down to Twofold Bay, and in some sheltered open coast locations ().

Posidonia australis

Posidonia australis (strapweed) is used to map seagrass extent in NSW because it is abundant and forms stable meadows. Maps of the extent of the different seagrass species can be viewed on the NSW DPIRD Estuarine Habitat Dashboard.

Populations of Posidonia australis are listed as endangered under State legislation in several areas, including:

- Botany Bay

- Brisbane Water

- Lake Macquarie

- Pittwater

- Port Hacking

- Port Jackson.

Nine estuaries have been remapped since 2020 (see Figure W3.3).

Batemans Bay, Bermagui River and Pambula Lake show moderate to severe declines in seagrass extent since the 2000s. More work is needed to understand why this has occurred. Large scale sand movement may have contributed at Bermagui River.

Increase in area was seen in St George, Merimbula, Twofold Bay and Port Hacking. Despite overall increases across many estuaries, losses were still apparent in many urbanised estuaries. Further, losses occurred at individual sites from localised impacts.

Figure W3.3a: Area (ha) of Posidonia australis in NSW estuaries remapped within the past five years

Notes:

Only estuaries remapped since 2020 are presented.

Data from tributaries of Twofold Bay have been amalgamated here.

Areas for any mapping times since 2000 are included to enable an assessment of longer-term trends.

Figure W3.3b: Area (ha) of Posidonia australis in NSW estuaries remapped within the past five years

Notes:

Only estuaries remapped since 2020 are presented.

Data from tributaries of Batemans Bay have been amalgamated here.

Areas for any mapping times since 2000 are included to enable an assessment of longer-term trends.

Figure W3.3c: Area (ha) of Posidonia australis in NSW estuaries remapped within the past five years

Notes:

Only estuaries remapped since 2020 are presented.

Areas for any mapping times since 2000 are included to enable an assessment of longer-term trends.

Transient seagrasses

Transient seagrasses are not as stable as Posidonia australis. They include:

- Zostera capricorni subspecies muelleri (eelgrass), common in most estuaries

- Halophila species (paddle weed)

- Ruppia species (tassel weed or widgeon grass).

Large changes in the extent of transient seagrasses (dominated by Zostera) over short time periods complicate determining long-term changes ().

Remapping since 2020 in 18 estuaries (see Figure W3.4) reveal substantial declines in transient seagrass area since the early 2000s in area or percentage:

- Smiths Lake (loss of 278ha or 94%), Lake Macquarie (220ha, 16%) and the Hastings River (113ha, 78%)

- Mooball Creek (2ha, 98%), Cudgera Creek (3ha, 97%) and Cudgen Creek (1ha, 92%).

Smiths Lake and Cudgera Creek have fluctuating environmental conditions that correlate to large variations in Zostera abundance (). Work is currently underway to assess whether other declines might be related to heavy rainfall which typically has disproportionately large effects in mature barrier river estuaries ().

Coverage has increased in six of the mapped estuaries:

- Hawkesbury River (30ha, 77%)

- St Georges Basin (28ha,16%)

- Port Hacking (23ha, 62%)

- Pambula Lake (7ha, 40%)

- Merimbula Lake (4ha, 7%)

- Bermagui River (1ha, 5%).

The extent of seagrasses has declined by nearly 25% from 2,604ha in the early 2000s to 1968ha when remapped over the last 4 years.

Figure W3.4a: Area (ha) of transient seagrasses in NSW estuaries remapped within the past five years

Notes:

Transient seagrasses (non-stable seagrass population) are dominated by Zostera.

Only estuaries remapped since 2020 are presented.

Figure W3.4b: Area (ha) of transient seagrasses in NSW estuaries remapped within the past five years

Notes:

Transient seagrasses (non-stable seagrass population) are dominated by Zostera.

Only estuaries remapped since 2020 are presented.

Figure W3.4c: Area (ha) of transient seagrasses in NSW estuaries remapped within the past five years

Notes:

Transient seagrasses (non-stable seagrass population) are dominated by Zostera.

Only estuaries remapped since 2020 are presented.

Data from tributaries of Twofold Bay are amalgamated here.

Figure W3.4d: Area (ha) of transient seagrasses in NSW estuaries remapped within the last 5 years

Notes:

Transient seagrasses (non-stable seagrass population) are dominated by Zostera.

Only estuaries remapped since 2020 are presented.

Data from tributaries of Batemans Bay are amalgamated here.

Drivers of seagrass habitat loss

There are many causes of local losses of Posidonia australis ().

Recent declines in seagrass coverage were most strongly associated with:

- the presence of large areas of artificial structures in estuaries (jetties and pontoons)

- distance from the ocean (greater losses were more common in the upper reaches of estuaries)

- boating and fishing activities

- combined effects of the above stressors and contamination ().

Increased numbers of boat moorings, jetties, pontoons and aquaculture leases are associated with increased fragmentation (breaking apart) of Posidonia australis meadows across NSW estuaries ().

Once a meadow becomes fragmented it is more likely to shrink in area and become less connected. This fragmentation then influences ecological processes and the movement of marine animals. Fragmentation of meadows is greatest in Port Jackson, Botany Bay, Brisbane Water and Lake Macquarie ().

Losses of transient seagrasses in estuaries have been related to flood events, which can reduce seagrass density. Floods and other environmental changes can also trigger reproduction of Zostera ().

Research by DPIRD is investigating whether these declines in Zostera indicate sustained losses or short-term declines with longer-term fluctuations.

Kelp and seaweeds

Kelp coverage has declined in NSW.

Kelp forests are important marine habitats that provide food and shelter for many rocky reef species. They are threatened by a range of stressors, including marine heatwaves, ocean warming, ocean acidification and pollution (; ; ).

When kelp and seaweeds (also known as macroalgae) are removed from rocky reefs, areas of rock encrusted with coralline algae (with flat crusts) can remain – called barrens – or areas transition into low lying algal turfs.

Trends in the abundance and condition of macroalgae have only been monitored systematically across NSW by DPIRD – Fisheries since 2019. Trends are preliminary and data over longer periods is needed to understand kelp forest condition.

Kelp cover has been mapped at six sites (see Figure W3.5). All sites have shown a decline in the percentage coverage of kelp since 2019, the largest being seen in Batemans Bay and Port Stephens.

Figure W3.5: Kelp cover (%) at NSW monitoring sites, 2019–23

Notes:

Based on average across six fixed 200-metre-long towed video transects at three sites at each location.

Surveys conducted on inshore reefs at depths from 5m to 30m.

Drivers of change in kelp and seaweeds

Previous video surveys have identified losses of kelp from offshore reefs on the Mid North Coast. These losses correlate with warming and increasing abundance of tropical herbivorous fishes (). Recent kelp losses within estuaries have been linked to flooding caused by severe weather events ().

Research is investigating the reasons for these changes, focusing on linking them to recent La Niña conditions and identifying possible refugia (places of safety) for kelp as oceans warm ().

When large macroalgae are removed from a rocky reef and sea urchins dominate, the reef is called a barren. This usually occurs from increased predation on seaweed, storm activity, reduced salinity or pollution (). Barrens occur across most NSW rocky reefs, but they tend to be larger and more numerous along the South Coast ().

No significant changes in the extent of barrens have been observed ().

Catchment disturbance

The level of coastal catchment disturbance in NSW was assessed most comprehensively in 2017 by the statewide threat and risk assessment for the NSW marine estate. No statewide assessment has been completed since, though risks will have increased in the past seven years with the increases in population, development and climate change.

This work identified that 93 of the 185 estuaries in NSW as sensitive to impacts from land use and potential changes (). The biggest risks were associated with population density (40% of catchments) and nutrient increase (37% of catchments) ().

Most coastal catchments in NSW have some level of land use activity or development. The causes of coastal catchment disturbance include population growth, agricultural expansion, and industrial and commercial activities (; ).

Estuaries with more catchment disturbance have also had poorer chlorophyll-a and turbidity results. See the Estuarine water quality section.

Understanding these disturbances is crucial because they can degrade water quality, disrupt ecosystems, and reduce the resilience of coastal environments to climate change impacts ().

Further research is required to establish the status of catchment disturbance and its impacts.

Coastal fish communities

Subtidal reef fish

The abundance and diversity of subtidal reef fish in NSW has been relatively stable in the past decade since systematic sampling has been done. Longer-term data will help us better understand these trends.

Subtidal reef fish inhabit the areas of a reef located below the low tide mark, which are constantly submerged. These fish include many endemic, or culturally and socially valued, species, such as pink snapper (Chrysophrys auratus), grey morwong (Nemadactylus douglasii), eastern blue groper (Achoerodus viridis) and southern Maori wrasse (Ophthalmolepis lineolatus).

DPIRD monitors the diversity and abundance of rocky reef fishes using baited remote underwater video.

Find out more about subtidal reef monitoring.

Fish abundances and diversity have been systematically sampled in the Tweed–Moreton, Manning and Batemans bioregions since late 2010 and in the Hawkesbury bioregion since 2019. Fish are observed at numerous sites in each bioregion to provide a representative selection (; ).

Coastal fish diversity, measured as species richness (the number of species per sample), has been relatively stable through time in all bioregions (see Figure W3.6). Generally, species richness has been higher in the Northern region (Port Stephens to the Queensland border) than in the Central or Southern regions. Fish diversity increased sharply in the Southern region in 2022.

Figure W3.6: NSW coastal fish diversity, 2010–22

Notes:

Northern, Central and Southern regions correspond with definitions of the Marine Estate Management Strategy.

The total relative abundance of coastal fish (measured by total maximum number) was also relatively stable over time (see Figure W3.7). Abundance was consistently higher in the Northern region than in the Central or Southern regions. Abundance increased sharply in the Southern region in 2022, mirroring the increase in species richness in the same area. Analyses of future data will provide an indication of whether this increase in the Southern region was a fluctuation or is part of a long-term trend.

Figure W3.7: NSW coastal fish abundance, 2010–22

Notes:

Northern, Central and Southern regions correspond with definitions of the Marine Estate Management Strategy.

Fisheries stocks

There is limited data available to assess the statewide trends of coastal fish species, but the Status of Australian Fish Stocks reports provide an indication of the population health of many of the key recreational and commercial fisheries species.

In 2023, the report included stock numbers for 92 freshwater and marine species (see Figure W3.8), an increase on the 85 assessed in 2020. Since then, there has been a:

- 6% increase in stocks assessed as depleted

- 3% decline in stocks assessed as sustainable

- 2% decline in undefined stocks

- 2% increase in the number of stocks showing negligible change.

The slight increase in the proportion of stocks assessed as depleted is the result of several undefined populations such as abalone, Murray cod and golden perch classified as depleted due to more detailed stock assessments being completed for these species. The following are examples of species in each stock status:

- Sustainable: eastern rock lobster (Sagmariasus verreauxi), dusky flathead (Platycephalus fuscus), eastern school whiting (Sillago flindersi)

- Depleted: Spanish mackerel (Scomberomorus commerson), grey morwong (Nemadactylus douglasii), redfish (Centroberyx affinis)

- Depleting: blue swimmer crab (Portunus armatus)

- Recovering: mulloway (Argyrosomus japonicus)

- Undefined: black bream (Acanthopagrus butcheri), estuary cobbler (Cnidoglanis macrocephalus), hapuku (Polyprion oxygeneios)

- Negligible: bastard trumpeter (Latridopsis forsteri), pale octopus (Octopus pallidus).

The status of blacklip abalone (Halotis rubra rubra) is complex. It is described as depleted in one Spatial Management Unit, depleting in two Spatial Management Units and sustainable in another. The sustainable area is about 75% of total stock ().

Figure W3.8: Status of Australian fish stocks in NSW, 2020–23

Community concerns with water quality

Enviro Pulse () is a quarterly survey that asks a sample of NSW residents a range of questions on their environmental behaviours, experiences and motivations.

Enviro Pulse indicates that fewer NSW residents feel concerned about water pollution in 2025 than they did in March 2021 (see Table W3.3).

Table W3.3 Concern about water pollution in NSW, March 2021 to March 2025

| Mar 21 | Mar 22 | Mar 23 | Mar 24 | Mar 25 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water pollution | 59% | 57% | 53% | 47% | 50% |

| Number surveyed | 1,004 | 1,016 | 1,011 | 996 | 960 |

Residents were also asked to rate satisfaction with water quality and cleanliness near where they live. In 2025,satisfaction with water quality of rivers and lakes, and with cleanliness of beaches and oceans is on par with the 2021 baseline, having recovered from the decline in 2022 caused by an exceptionally rainy season (Table W3.4).

Table W3.4: Satisfied or very satisfied with the water quality and cleanliness in NSW, March 2021 to September 2025

| Mar 21 | Mar 22 | Mar 23 | Mar 24 | MAR 25 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleanliness of beaches and oceans near me | 58% | 50% | 59% | 61% | 61% |

| Water quality of rivers or lakes in my local area | 54% | 49% | 55% | 59% | 59% |

| Number surveyed | 1,004 | 1,016 | 1,011 | 996 | 960 |

Pressures and impacts

Development and recreation

As 85% of our population lives within 50km of the coast (), development of our catchments, coastlines and offshore areas continues to put significant pressure on the environment.

Increasing land use intensification (increased urban and agricultural development), water pollution (urban and agricultural runoff), and shoreline infrastructure and related recreational activities (jetties, pontoons, piers and boating) due to a growing population all pose continued risks to the health of our coast and estuaries.

See the Threats to the NSW marine estate section of this topic for the top 10 environmental threats.

These threats will continue to increase as our population grows.

See the topic for more information about projected growth.

Catchments

Urban and agricultural development in coastal catchments can result in:

- habitat alteration and fragmentation of ecosystems

- eutrophication and algal blooms

- increased bacterial concentrations and pollutants in coastal waterways.

Changes in tidal levels from modifications to estuary entrances have also had major consequences for critical marine habitats, including beaches, saltmarsh, mangroves, seagrasses and mudflats (). This creates flow-on consequences for the plants and animals that rely on these habitats.

Sea level rise will further increase the impact of changes in tidal levels.

See the topic for more information about sea level rise.

Coastlines

Coastline and foreshore development, such as housing, parklands and break walls, alter sand dunes. This can result in:

- increased coastal erosion

- changes in beach sand dynamics

- removal of important coastal vegetation

- changes in or loss of animal habitats.

These developments can alter the flow of water, changing the transportation of sediments, nutrients and food resources necessary for estuarine habitat maintenance and life cycles of vegetation and animals. This can affect the whole ecology of an area, decreasing:

- water quality

- habitat coverage

- capacity to support plants and animals

- ecosystem health.

Coastal development, particularly street lighting, recreational activity and agriculture, can alter behaviour and harm habitats for migratory seabirds, shorebirds and fish breeding (; ; ; ).

Find out why shorebirds are important and how you can protect them.

Commercial and recreational fishing have potential cumulative impacts on fish groups and coastal food webs (). These impacts, including overfishing of certain species, may reduce the abundance and diversity of fish communities.

Commercial fisheries operate in 76 of the 184 estuaries along the NSW coast ().

Offshore

Offshore development, through offshore wind farms proposed to meet renewable energy needs, has the potential to harm the marine environment through:

- increased noise levels

- pollution risk during construction

- increased marine traffic

- development of associated land-based infrastructure

- alteration to seafloor habitats.

Offshore windfarms may also pose a significant risk to the seabird species that breed on our offshore islands. Further research is required to determine the likely impacts of any future offshore developments.

Pollution

Water pollution from runoff, litter and debris continue to threaten coastal and marine environmental, social, cultural and economic values (; ).

The impacts of water pollution can be devastating for the environment, communities and culture.

Runoff

Pollutants can enter coastal and marine environments through stormwater and agricultural and sewage runoff during periods of higher rainfall.

Runoff from these sources can carry a range of nutrients, heavy metals and contaminants that are transported to coastal ecosystems.

Nutrients

Increased nutrient loads from urban stormwater discharge and diffuse agricultural runoff into estuarine waters can result in algal blooms, particularly of harmful or toxic cyanobacteria (). These events lower the water quality, affecting recreational and swimming areas and reducing seafood quality, as seen following bloom events in the Hawkesbury River ().

Large algal blooms can also reduce the amount of oxygen in the water and kill large numbers of fish. One of the most significant water pollution events attributed to an algal bloom occurred in Newcastle in February 1993, resulting in significant fish kills ().

While fish kills caused by algal blooms are less common in coastal areas than in inland waterways, they are becoming common in many estuaries, and eutrophication (enrichment of nutrients) poses a serious threat to estuarine ecosystems ().

Heavy metals

Pollution from mercury, lead, copper and other heavy metals, and by pesticides is a localised problem in some areas, including Lake Macquarie, Sydney Harbour and the Hunter River (). Other sources include metals mobilised by acidic runoff from oxidised acid sulfate soil landscapes, such as drained coastal floodplains.

Elevated metal and organic chemical concentrations in sediments have been linked to significant risk to aquatic organisms (). For example, heavy metal pollution can disrupt respiratory, cardiovascular and reproductive systems in fish ().

Sediment

Excessive sediment transport can change the characteristics of streambeds and shorelines and alter habitats. Sediments can carry pollutants in them, including heavy metals and organic compounds which are harmful to humans, plants and animals.

Sediment can smother aquatic habitats and limit light penetration impacting seagrasses and other aquatic plants.

See the Seagrasses section of this topic for more information about the decline in seagrasses.

Licensed discharges

Discharges, including nutrients, heavy metals and sediments, can originate from point or diffuse sources.

Point sources of pollution include urban stormwater and licensed discharge points.

Diffuse sources include runoff from a broader area; for example, agricultural, urban or industrial areas.

The EPA regulates point source discharges from industry through the Load-based licensing scheme. Monitoring covers loads of total nitrogen, total phosphorus and total suspended solids discharged into open marine waters and estuaries.

Loads discharged into estuarine environments have generally decreased since 2011–12, with fluctuations in the discharge of suspended solids tending to reflect wet and dry periods.

See the topic for more information about these cycles.

Marine litter and debris

Marine litter is human-generated or processed material that is intentionally or accidentally disposed of, abandoned or transported into coastal and marine environments.

In NSW, microplastics, fishing lines and nets, ropes, fibres and plastic fragments pose some of the greatest threats to our coastal and marine environments ().

Entanglement in and ingestion of debris are key threats to marine species, particularly threatened species, such as seabirds, turtles and whales (). The recovery of populations of threatened species, such as humpback whales, is likely to result in more accidental entanglements ().

See the topic for more details on plastic waste.

Cigarettes are the most littered item on beaches, while glass fragments, polystyrene, and soft and hard plastics are common in NSW estuaries (). Monitoring as a part of the Key Littered Items Study shows significant decreases in targeted items such as single-use plastic bags (74% reduction) and beverage containers thanks to the Return and Earn container deposit scheme (61% reduction) (; ).

Threats to Aboriginal peoples’ cultural connection to Sea Country

Significant issues threaten Aboriginal people’s connection to Sea Country, including:

- restricted access to Sea Country resources and culturally significant sites

- natural habitat damage and loss

- overcrowding and development of cultural sites

- poor water quality

- climate change.

These threats reduce the amount and quality of seafood, and diminish totemic or culturally significant wildlife.

They affect emotional and mental health, cultural identity, cultural practices, traditional food collection practices, and Aboriginal people’s ability to pass down traditional teachings to future generations ().

Actions being taken in response to these concerns are part of Initiative 4 – protecting the Aboriginal cultural values of the marine estate as part of the Marine Estate Management Strategy.

Cultural fishing is important in the lives of coastal Aboriginal peoples, forming part of their connection to Sea Country and culture (). Aboriginal peoples view fishing as a way to honour their ancestors and connect spiritually to the marine world ().

As custodians of the sea, Aboriginal communities see themselves as responsible for its protection and ensuring its continued sustainability for future generations (). This responsibility is reflected in traditional fishing practices that are based on the principle of taking only what is needed and respecting the delicate balance of the marine ecosystem (). The act of fishing also serves in the transmission of cultural knowledge and traditions from generation to generation (). Sharing the catch strengthens social bonds and reinforces the importance of community within Aboriginal cultures ().

This essential connection is challenged by contemporary regulations ().

Restrictions, such as permit requirements for fishing in no-take zones, can hinder traditional practices and limit the ability of Aboriginal people to maintain their cultural heritage ().

In addition, significant portions of Aboriginal cultural heritage exist underwater, having been submerged by sea level rise 8,000 years ago (). There is currently a lack of awareness and protection of these underwater cultural sites ().

Find out how climate change affects the Gumbaynggirr people.

Currently, protections of Sea Country are focused primarily on biodiversity and shipwreck conservation, with limited recognition of the importance of Aboriginal cultural heritage (). The absence of frameworks for protecting culturally important marine ecosystems leaves these submerged sites vulnerable to the increasing pressures of human activities and climate change (; ).

Learn how cultural approaches can address threats to Yuin Country.

Diseases and invasives

Monitoring and management of aquatic animal diseases is important, as they can threaten the biodiversity of our marine estate.

Introduced pathogens and parasites, or the amplification of endemic diseases, can have devastating impacts on native species, aquatic industries and the safety of seafood.

Diseases

Several diseases are currently of concern in NSW marine and estuarine environments:

White spot is a highly contagious viral disease of prawns and other farmed crustaceans that can result in high mortality. It has recently been detected in the Evans Head and Richmond River areas.

See the White Spot website for more information.

Epizootic ulcerative syndrome, also known as ‘red spot’, causes ulcers in fish species such as bream, mullet and whiting. In early 2021 it was reported in fish from the estuaries of the Macleay, Brunswick, Richmond, Clarence and Hastings rivers. In 2022 it was detected in samples from the Myall River, the Hastings River and waterways near Grafton following reports of ulcerated fish to DPIRD.

Queensland unknown (QX) disease can cause mass mortality in Sydney rock oysters. First found in south-east Queensland, QX has caused the near collapse of the Sydney rock oyster industry in various estuaries, including the Hawkesbury River in 2004 and the Port Stephens estuary in 2021.

Surveillance in 2022 determined that the Port Stephens area was at high risk for this disease, and clause 49 of the Biosecurity Regulation 2017 was updated in response.

See the QX disease website for more information.

Avian influenza (H5N1 and variants) has affected wild birds (and mammals) on several continents but has yet to reach Australia. Its short incubation period means that no migratory seabirds or shorebirds that are infected in other parts of the world reach our region alive. These diseases may eventually occur here.

Marine invasive species

Marine invasive species include plants, algae, invertebrates and animals, often introduced from overseas. They can take over habitats, directly compete with native species for food, and introduce viruses and disease.

Some of these are native to other regions of Australia but have been brought into NSW on ships or via the aquarium trade.

The following marine invasive species have been detected in NSW, with varying degrees of impact and spread:

- green macroalga (Caulerpa taxifolia)

- green shore crab (Carcinus maenas)

- European fan worm (Sabella spallanzanii)

- Japanese goby (Tridentiger trigonocephalus)

- New Zealand screw shell (Maoricolpus roseus)

- wild Pacific oyster (Magallana gigas)

- striped barnacle (Amphibalanus amphitrite)

- yellowfin goby (Acanthogobius flavimanus)

- non-native sea squirt (Botrylloides giganteus)

- devil’s tongue weed (Grateloupia turuturu)

- red macroalga (Pachymeniopsis lanceolata)

- lightbulb sea squirt (Clavelina lepadiformis)

- vase tunicate (Ciona intestinalis)

- dead man’s fingers (Codium fragile fragile)

- pleated sea squirt (Styela plicata).

The State’s offshore islands are now free of vertebrate pest species, though their impacts remain in some cases; notably, species driven extinct by them cannot be recovered.

Many islands remain threatened by invasive weed species.

Invasive weeds on islands can significantly modify habitat and compete with endemic species (). Unchecked, they can also have significant impacts on the structure of vegetation, with consequent impacts on nesting habitats for seabirds ().

Climate change

Climate change has the potential to significantly alter our coasts and marine environments through:

- altered ocean currents and nutrient levels

- sea level rise

- warmer sea surface water including marine heatwaves

- ocean acidification

- altered weather patterns, such as storm and cyclone activity ()

- localised impacts on salinity caused by freshwater ingress.

Changes in the movement and flow intensity of the East Australian Current could greatly affect future species distributions in NSW (; ), potentially affecting:

- seafood nutritional properties (; )

- species interactions ()

- patterns of connectivity and settlement of organisms (; ).

Sea level rise presents significant challenges for communities along the coast and around our tidal waterways, including:

- changes to the coastal processes that move sand around beaches and dunes

- exacerbated impacts of major storms and floods ()

- increased impacts on cultural sites on dunes and foreshores, including erosion of middens and burial sites

- inundation of coastal floodplains and/or impairment of existing drainage viability impacting current land uses

- loss of sand from beaches, and other changes due to sea level rise, storm surges and inundation.

Increasing sea surface temperatures, often known as ‘marine heatwaves’, have consequences for the species range of marine and estuarine animals and plants (; ). Some plants and animals along the NSW coastline are already moving south, such as the green moon wrasse (Thalassoma lutescens) ().

Climate change will exacerbate impacts on the NSW marine environment. Significant effects are expected to occur across south-eastern Australia (; ; ), including changes to:

- the distribution and abundance of marine species ()

- variations in and timing of life-cycle events

- physiology, morphology and behaviour (such as rates of metabolism, reproduction and development)

- biological communities via altered species interactions.

Ocean acidification is already affecting calcifying animals, such as snails, oysters, zooplankton and corals (; ; ; ). Marine molluscs (oysters, abalone and whelks) are particularly vulnerable to these effects during their reproductive stages (; ).

Acidification has reduced the rate of successful fertilisation in Sydney rock oysters, resulting in a smaller size, longer time to develop and increased abnormality of larval stages (). Combined with other stressors this has the potential to limit survival ().

See the topic for more details.

Bushfire impacts on coastal water quality

Bushfires have the potential to increase erosion and decrease water quality in NSW waterways.

Bushfire impacts are strongly related to waterway type, fire severity and post-fire conditions, particularly the intensity and frequency of post-fire rainfall.

Intermittently closed and open lakes and lagoons are most susceptible to significant water quality impacts, as they are less frequently flushed by seawater than estuaries that remain open to the ocean ().

Declines in water quality are most significant immediately following the first rainfall events that occur after fire and can remain for up to two years.

During the 2019–20 Black Summer bushfires, nearly every catchment in coastal NSW suffered, as fires burned into wetter environments that are reported to ‘not normally burn.’ Overall, 30% of the total area of all coastal catchments in NSW was burned, totalling 5,507,400 hectares, with significant implications for erosion and water quality ().

Water quality monitoring data from 22 NSW estuaries revealed sudden and severe declines in estuary water quality following heavy rainfall in the first one to two years after fire, owing to elevated erosion rates and the transport of ash, debris, sediment and nutrients into waterways, reservoirs and estuaries.

The breakdown of organic matter can reduce dissolved oxygen concentrations in receiving waters for up to a month. When combined with elevated sediment, nutrient and dissolved carbon loads, this can trigger potentially hazardous algal blooms and fish kills ().

Responses

Strategic management

Marine Estate Management Strategy

The Marine Estate Management Strategy 2018–28 outlines how the NSW Government will address priority threats to the marine estate, including threats to environmental assets and protect their benefits to our community, Aboriginal peoples and the economy.

More than $285m is being invested in meeting the following nine management initiatives over the 10-year lifetime of the strategy to:

- improve water quality and reduce litter

- deliver healthy coastal habitats with sustainable use and development

- plan for climate change

- protect Aboriginal cultural values of the marine estate

- reduce impacts on threatened species

- ensure sustainable fishing and aquaculture

- enable safe and sustainable boating

- enhance social, cultural and economic benefits

- deliver effective governance.

Implementation of the 53 management actions in the strategy involves partnerships with agencies, industry, key stakeholders and community to collectively address social, cultural, economic and environmental threats to the marine estate in a coordinated approach.

Management of Sea Country by Aboriginal people is embedded in the strategy to ensure that traditional knowledge and cultural practices be considered, be shared and influence decision-making.

NSW marine protected areas

Marine protected areas play an important role in conserving marine biodiversity and ecosystems while delivering a range of benefits to the community.

Statutory management planning for marine parks has seen the development of a draft network management plan for the five mainland marine parks and preliminary work to inform a management plan for Lord Howe Island.

See the Overview section of this topic for more information.

Coastal Management Programs

Coastal Management Programs (CMPs) are prepared by local councils in consultation with their communities and public authorities to set long-term strategies for the coordinated management of the coast and estuaries.

Several councils are developing CMPs to manage their coastal zones where waterways and coastal zones are shared, such as the Hawkesbury–Nepean River system.

Management actions are often supported by funding from the Coastal and Estuary Grant Program.

At the end of 2023, 11 CMPs had been certified and are being implemented. A further 50 are being prepared by councils with financial and technical support from the NSW Government.

NSW Blue Carbon Strategy 2022–2027

The NSW Blue Carbon Strategy 2022–2027 supports the restoration of coastal biodiversity and ecosystems while simultaneously working towards reducing emissions.

‘Blue carbon’ is the term used to describe the carbon captured and stored by marine and coastal ecosystems.

Blue carbon ecosystems, which include seagrasses, mangroves and saltmarsh, can store substantially more carbon per area than land-based forests and, if undisturbed, can store it in soils for many years.

Projects that restore blue carbon ecosystems, such as the reintroduction of tidal flows to restore coastal wetlands, can reduce emissions significantly and may enable carbon credits to be earned.

Fisheries Management Strategies

NSW DPIRD have prepared strategies for each of the major fisheries and activities they manage to ensure the sustainable use of fisheries resources and limit the impacts on the environment. Where fisheries resources have become depleted, recovery plans are put in place to ensure rebuilding of the stocks of these species in an appropriate time period.

A key component of updating these strategies is the development of Harvest Strategies containing pre-defined rules agreed to by fishers that enact management before fish stocks become depleted.

Monitoring our coasts

Marine Integrated Monitoring Program

The Marine Integrated Monitoring Program, which began in 2018:

- monitors the conditions and trends of environmental assets and the community benefits derived from the NSW marine estate

- evaluates the effectiveness of actions aimed at reducing priority threats and risks

- fills knowledge gaps (social, cultural, economic, and environmental) identified in the 2017 NSW Marine Estate Threat and Risk Assessment.

Marine Debris Threat and Risk Assessment

Published in 2023, the Marine Debris Threat and Risk Assessment comprehensively evaluates the impact of marine debris on the marine estate of NSW.

It identifies the sources, distribution and types of marine debris to explain the associated risks to environmental and social values. It provides tools and knowledge to help stakeholders and managers better manage the risk of marine debris.

Working with Traditional Owners

Coastal monitoring

A new community wellbeing monitoring program under the Marine Integrated Management Program includes the Connections to Sea Country – Aboriginal Peoples of Coastal NSW survey. The survey themes include interactions with Sea Country, importance of Sea Country to quality of life, cultural connections to Sea Country, community perceptions of environmental health, impact of key threats on cultural connections, perceptions of and attitudes to Sea Country management, employment related to Sea Country, and involvement and interest in government-led Sea Country programs (for example, Ngiyambandigay Gaagal Indigenous Protected Area)

DCCEEW has developed guidelines for engaging Aboriginal communities, knowledge holders, and Aboriginal-led organisations when preparing coastal management programs under the Coastal Management Act 2016.

The Coastal Management: Creating culturally safe opportunities when engaging First Nations people guide supports engagement with First Nations people through approaches that are culturally safe, respectful and reciprocal.

Pest surveillance and removal

The 5-year Marine Pest Surveillance Plan (2022–2026) developed by DPIRD Aquatic Biosecurity directs biannual surveillance of 23 priority marine pest species at the six largest ports in NSW. It focuses on early detection and response.

Environmental incidents

The EPA, LLS and DPIRD led Flood Recovery Programs following the 2021–22 periods of intense flooding on NSW coast, particularly in the Northern Rivers. Programs included:

EPA Water Quality Monitoring Program (concluded):

- removing 24,438 cubic metres of debris from affected waterways from the Shoalhaven to the Tweed rivers

- water quality monitoring in recovering systems, collecting 11,000 samples across 29 local government areas

- an Aboriginal knowledge project on Bundjalung Country sharing perspectives and weaving together water quality knowledge

- additional agricultural chemical clean-up, contaminated land assessments, and illegal dumping and flood waste recovery projects ().

DPIRD Estuary Asset Protection Program (ongoing)

An action plan to protect and support the recovery of estuarine ecosystems and reinstate their resilience to future disasters including assessment, prioritisation and on-ground works in the areas of:

- Aboriginal Cultural Heritage protection

- Riverbank resilience

- Instream obstructions

- Key habitat and threatened species resilience

- Estuarine infrastructure

- Monitoring and research

LLS Riverbank Rehabilitation Program (ongoing)

A program to assist longer-term rehabilitation and future-proofing of flood damaged riverbanks through targeted on-ground works and support for flood impacted land managers.

Future opportunities

The NSW Government needs to continue to develop and implement strategies to plan for climate change and prevent a decline in the quality of coastal, estuarine and marine environments.

The poor water quality in some highly urbanised estuaries suggests that stormwater runoff and new urban development can be managed better to maintain the health of estuaries and coastal lakes and the desirability of coastal lifestyles.

A molecular database is being generated for NSW estuaries to help assess biodiversity in estuaries and allow assessment of the occurrence and range shifts of finfish, crustaceans and molluscs statewide.

While trends in aquatic vegetation have been monitored systematically, understanding coastal vegetation, such as dune grasses, coastal heath and woodland, and back-beach swamps, is also important for the overall health of coastal environments.

Vulnerability to inundation and coastal erosion should be a significant consideration in the location and planning of future developments for an expanding population.

Other areas for further improvement are possible:

- Improved collaboration between community, governments and research institutions to further enhance the shared management of the marine estate and its resources.

- Creation of opportunities to listen to Aboriginal peoples in decision-making roles in inclusive and respectful settings.

- Enhancement of indicators of water health by including additional water monitoring datasets, such as harvest area classifications and analysis of historic data trends within the NSW Shellfish Program dataset (faecal coliforms, E. coli, phytoplankton, salinity, temperature and water level monitors).

- Improved communication and education opportunities in all aspects of estuarine, coastal and marine management to raise awareness, enhance community stewardship and influence positive behaviours.

- Strengthening ecosystem health monitoring programs and sharing data to provide sound scientific input into decision-making.

- Boosting social, cultural and economic research and monitoring capabilities within government to ensure that decisions be comprehensively based, to achieve holistic management of estuaries, coasts and oceans.

- Further development and expansion of risk assessment methods to help protect and rehabilitate the environment in the most resource-efficient manner.

- Re-evaluation of emerging threats and accelerating risks from known threats, such as those threats posed by climate change in the near term.

- Consistent application of the risk-based framework for urban and rural waterway health () across NSW as a best-practice protocol for managing the impacts of land-use change on waterway health.

- Clarification of agency roles and responsibilities in relation to diffuse-source water pollution in NSW.

- Sentinel monitoring to detect reinvasion of offshore islands by pests.

- Baseline monitoring of seabird populations and their breeding success on offshore islands to track changes supporting research into the marine biodiversity of NSW.

There is scope to introduce qualitative information on coastal, estuarine and marine species and ecosystems of significance to Aboriginal people, to understand how they are faring and ways to care for coastal, marine and estuarine species and their habitats.

Qualitative data collection includes oral stories and knowledge about Aboriginal culture and practices. The 2021 EPA Aboriginal Peoples Knowledge Group identified a need for management authorities to apply Aboriginal cultures and practices in the care, protection and management of species, habitats and the overall environment. The group identified this emerging research as being essential for understanding and managing all aspects of environmental and ecosystem health.

References

NSW EPA unpub., Flood Recovery Program Data (unpublished), NSW Environmental Protection Agency, Sydney

Image source and description

Topic image:Yuin Country–Beecroft Peninsular. Aerial image of coast meeting land at Turtle Row. Photo credit: Silvan Bluett/DPIE (2021).Banner image:Topic image sits above Butjin Wanggal Dilly Bag Dance by Worimi artist Gerard Black. It uses symbolism to display an interconnected web and represents the interconnectedness between people and the environment.

Image source and description

Topic image:Yuin Country–Beecroft Peninsular. Aerial image of coast meeting land at Turtle Row. Photo credit: Silvan Bluett/DPIE (2021).Banner image:Topic image sits above Butjin Wanggal Dilly Bag Dance by Worimi artist Gerard Black. It uses symbolism to display an interconnected web and represents the interconnectedness between people and the environment.