Topic report card

Read a two-page summary of the Protected areas and conservation topic (PDF 296KB).

Overview

Protected areas are clearly defined areas of land or ocean, formally managed to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values ().

Conservation refers to the planned management of natural resources and protection of biological diversity (biodiversity) across landscapes. It includes measures to prevent biodiversity loss and to restore damaged habitats and ecosystems.

Why protected areas are important

Protected areas are a key component of conservation strategies and are managed to:

- safeguard biodiversity

- maintain ecosystems

- preserve and restore important habitats

- protect natural and cultural heritage

- build resilience to climate change.

Protected areas provide safe and healthy ecosystems for our native plants and animals. They also provide essential ecosystem services such as clean water, clean air, pollination and carbon storage. Ecosystem services have important social, economic and health benefits for human wellbeing.

Importantly, in NSW, protected areas also aim to provide opportunities for Aboriginal custodianship, access and connection with Country, and cultural practice. Joint management agreements give Aboriginal custodians a say in how Country is cared for through collaborative management of parks.

Networks of terrestrial (land-based) and marine (sea-based) protected areas aim to address biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation at international, national and sub-national levels.

The information in this topic focuses on land-based protected areas and conservation in NSW.

See the topic for more information on marine protected areas in NSW.

See the and topics for information on threats to native plants and animals in NSW, and monitoring and conservation programs.

Global and national frameworks and targets

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) provides an internationally recognised framework for protected areas which includes:

- six management categories, applied to a protected area on the basis of management objectives

- four broad governance types, recognising that different decision-making authorities and owners can be responsible for the management of protected areas ().

The IUCN framework and guidelines underpin the four governance types for protected areas in Australia’s National Reserve System (). These are:

- public protected areas (government owned)

- Indigenous Protected Areas

- private protected areas

- shared management reserves.

Australia is a signatory to international protocols and frameworks, including the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Aligning to these, Australian state and territory governments have agreed to support six new national biodiversity targets under Australia’s Strategy for Nature 2024–2030:

- Ensure no new extinctions of native species and support the recovery of threatened species.

- Protect and conserve 30% of Australia’s landmass and 30% of Australia’s marine areas by 2030 (National 30 by 30 Roadmap).

- Prioritise degraded areas under effective restoration by 2030 to recover biodiversity and improve ecosystem functions and services, ecological integrity and connectivity.

- Minimise the impact of climate change on biodiversity and increase its resilience.

- Eradicate or control invasive species in priority landscapes and minimise their introduction by 2030.

- Increase Australia’s circularity rate (by ensuring products are designed to be reused, repaired, recycled and repurposed) and reduce pollution and its impacts on biodiversity by 2030.

States and territories will implement measures and improve current programs to support efforts to meet these national targets.

National Reserve System

Australia has a network of formally protected terrestrial areas that make up the National Reserve System (NRS). Only areas that fall within the IUCN definition of a protected area form part of the NRS. These areas are protected through legal or other effective means and are managed in perpetuity (this means either permanently or for more than 99 years).

The NRS aims to conserve examples of our unique landscapes, plants, animals and important environmental values for future generations. By ensuring effective management of landscapes, a natural safety net is formed against some of our biggest environmental challenges, namely climate change and declining water resources.

See the Pressures and impacts section of this topic for more information.

Indigenous Protected Areas

Indigenous people have been protecting habitats, species and ecological functions for thousands of years. Formal recognition of these efforts by governments and the inclusion of Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) within the NRS began in 1997.

More than 50% of the NRS is made up of IPAs, but only 0.5% of the NSW NRS. Aboriginal communities voluntarily dedicate and manage their land as protected areas under a program jointly administered by the Australian Government and the National Indigenous Australians Agency. These areas hold deep cultural significance for Aboriginal peoples, who manage IPAs with the goal of protecting the environment and their cultural heritage.

By protecting habitats for threatened species and ecological communities, IPAs are making a significant contribution to Australia’s biodiversity conservation efforts ().

See the topic for more information.

Bioregions

The NRS rests on the Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA) framework of bioregions. These are large, geographically distinct areas of land with distinguishing characteristics, such as climate, ecological features and plant and animal communities.

The Australian land mass is divided into 89 bioregions and 419 subregions. Subregions are used to provide more detailed information about landscapes and are used for finer, regional-scale planning of protected areas and conservation.

See for information.

‘Comprehensive, adequate and representative’ system

Underpinning the NRS is the scientific framework, the ‘comprehensive, adequate and representative’ (CAR) system of protected areas. The system aims to protect examples of all regional ecosystems within the bioregions through both public and private land conservation.

- Comprehensive: refers to the inclusion in the protected areas network of examples of the full range of regional-scale ecosystems in each bioregion.

- Adequate: refers to the inclusion of enough of each regional ecosystem within the protected areas network to provide ecological viability and maintain the integrity of animal and plant populations, species and communities.

- Representative: builds on the principle of comprehensiveness to cover the variability within regional ecosystems across each bioregion.

See the Status and trends section of this topic for more information.

Collaborative Australian Protected Areas Database

The Collaborative Australian Protected Areas Database (CAPAD) holds information on protected areas that are part of the NRS and offers an interactive dashboard. It is maintained by the Australian Government and is updated every two years, most recently in 2022.

As at 30 June 2022, the total land area of Australia was 768,828,859 hectares (ha), of which 169,941,262ha, or 22.1%, was reserved within protected areas.

Currently, less than 6% of Australia’s protected areas are on private land.

See the interactive Australian Protected Areas Dashboard, as at 30 June 2022 for more information.

Protected areas system in NSW

The main land area of NSW includes all or part of 18 bioregions and 131 subregions of the IBRA framework, with Lord Howe Island contributing an additional bioregion and subregion.

The bioregions cover a diversity of landscapes, including sandy deserts, riverine plains, wetlands, rolling slopes and rocky ranges, rugged mountains, alpine environs, fragile wooded grasslands, rainforests, and coastal areas ().

The terrestrial protected area network (also called the protected areas system) on public and private lands throughout NSW includes a range of habitats and ecosystems, a diversity of plant and animal species, significant geological features and landforms, Aboriginal cultural heritage sites and landscapes, heritage buildings and historic sites.

Protected areas and Aboriginal access to Country

For Aboriginal peoples, colonisation has caused dispossession of their traditional lands and prevented access to Country, especially on private lands. Opportunities are now emerging for Aboriginal peoples and communities to access, protect and manage Country through formal and informal agreements on both public and private lands.

This includes through Aboriginal joint management agreements and partnerships with government agencies and non-government conservation organisations, and also through the establishment of Indigenous Protected Areas in NSW.

Public protected areas

Conservation in NSW is centred on public protected areas, in particular the national parks system and flora reserves, and relies on a mixture of biodiversity, conservation and land protection legislation. National parks and reserves, and flora reserves in State forests, currently make up almost 93% of the protected areas in NSW.

The NSW National Parks Establishment Plan 2008 sets out how new parks are established, and the conservation priorities for acquiring new land and enhancing the parks system. It is currently being reviewed, and a revised plan is under development by the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS).

The NPWS Aboriginal joint management program started in 1998 and, at 30 June 2024, around 30% of the national parks estate is jointly managed with Aboriginal peoples. There are also a number of joint management arrangements for areas of State forests.

Private protected areas

Many threatened ecosystems, plants, animals and cultural sites are found on privately owned land outside the protection of public protected areas.

With more than 70% of NSW’s land managed privately (), private land conservation is increasingly important in NSW to improve biodiversity conservation outcomes. Policies and programs have been established to increase the area of private land, including land leased from the Crown, that is managed as part of the formal protected areas network.

The Biodiversity Conservation Investment Strategy sets the NSW Government’s priorities and targets for private land conservation. It maps areas of the State into five Priority Investment Areas, guiding the investment priorities of the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Trust (BCT). The strategy explains the criteria and data used for the identification of priority investment areas.

To help to address the issue of dispossession of Aboriginal peoples from their traditional lands, especially from private lands, the BCT has developed ‘respect and recognition’ guidance to provide support for private landowners to meet and learn from local Aboriginal communities and knowledge holders about the cultural values of their properties. This is aimed at strengthening relationships between local Aboriginal communities and landowners and improving access to Country and a better understanding of how to care for Country.

See the topic for more information.

Many non-government organisations play an important role in private land conservation. They also partner with Aboriginal peoples to manage private protected areas and for conservation purposes. Some have long-standing relationships with Aboriginal communities.

Other areas managed for conservation

Areas of public and private land that do not meet the protected areas definition and requirements can still be managed for conservation purposes. They contribute to the overall aim of improving biodiversity conservation in NSW but do not count towards the formal network or targets. They include public land such as Crown land and State forest, private land under BCT agreements that are not permanent (term agreements), and other land owned by private individuals and business or non-government conservation organisations. Some may be eligible to become part of a proposed conserved areas network.

Conserved areas

Under the National Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (OECM) Framework, agreed to by the Australian, state and territory governments in June 2024, additional areas of high biodiversity value may now be eligible to become conserved areas.

Known as OECMs internationally, and conserved areas in Australia, they are lands which are recognised as providing ongoing suitable conditions for nature conservation although this is not their primary goal. This means they are places where formal protection is not possible, appropriate or supported.

Alongside the protected areas network, the conserved areas network will contribute to national and global targets to protect and conserve 30% of land by 2030.

Key legislation for the development of formally protected areas and biodiversity conservation in NSW, on both public and private land, is described in Table L2.1.

Table L2.1: Current key legislation and policies relevant to protected areas

| Legislation or Policy | Summary |

|---|---|

| Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 | Provides for land rights for Aboriginal persons in NSW. Provides for the creation of Aboriginal Land Councils, and for land to be vested in those Councils. |

| Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 | Aims to protect biodiversity and foster a productive, resilient environment while enabling ecologically sustainable development. Provides for private land conservation arrangements and funding in NSW. |

| Biosecurity Act 2015 (Commonwealth) | Manages biosecurity threats to plans, animal and human health in Australia and Australian territories |

| Crown Land Management Act 2016 | Allows for Crown reserves to be set aside for public purposes, including environmental and heritage protection. Facilitates the use of Crown land by Aboriginal peoples and enables co-management of dedicated or reserved Crown land. |

| Forestry Act 2012 | Provides for the dedication, management and sustainable use of State forests and other Crown-timber land for forestry and other purposes. All Flora Reserves contribute towards the National Reserve System. |

| Greater Sydney Parklands Trust Act 2022 | Provides for the management of the Greater Sydney Parklands Trust estate. Ensures the conservation of the natural and cultural heritage values, and the protection of the environment, within the parklands estate. |

| Local Land Services Act 2013 | Governs the management of natural resources, biosecurity and agricultural production in NSW. Private land with suitable types of property vegetation plans contribute towards the National Reserve System. |

| National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 | Aims to conserve the natural and cultural heritage of the state of New South Wales through the establishment of national parks and reserves. Parks and reserves under this Act contribute to the National Reserve System. |

| Native Title (NSW) Act 1994 | Sets out how native title rights must be recognised and protected. Section 211 preserves native title holders’ rights to hunt, fish, gather resources and undertake cultural activities. |

| Commonwealth Acts bringing effect to Indigenous Protected Areas | Indigenous Protected Areas are dedicated reserves formed by agreement between the Australian Government and Indigenous Australians. They are recognised as contributing to the National Reserve System. |

| Biodiversity Conservation Investment Strategy 2018 | Guides the NSW Government’s investment to deliver private land conservation programs in NSW. All permanent (in perpetuity) agreements administered by the Biodiversity Conservation Trust are recognised as contributing to the National Reserve System. |

Notes:

See the Responses section for more information about about how Protected areas and conservation is managed in NSW

Related topics: | | | | | |

Status and trends

Protected areas and conservation indicators

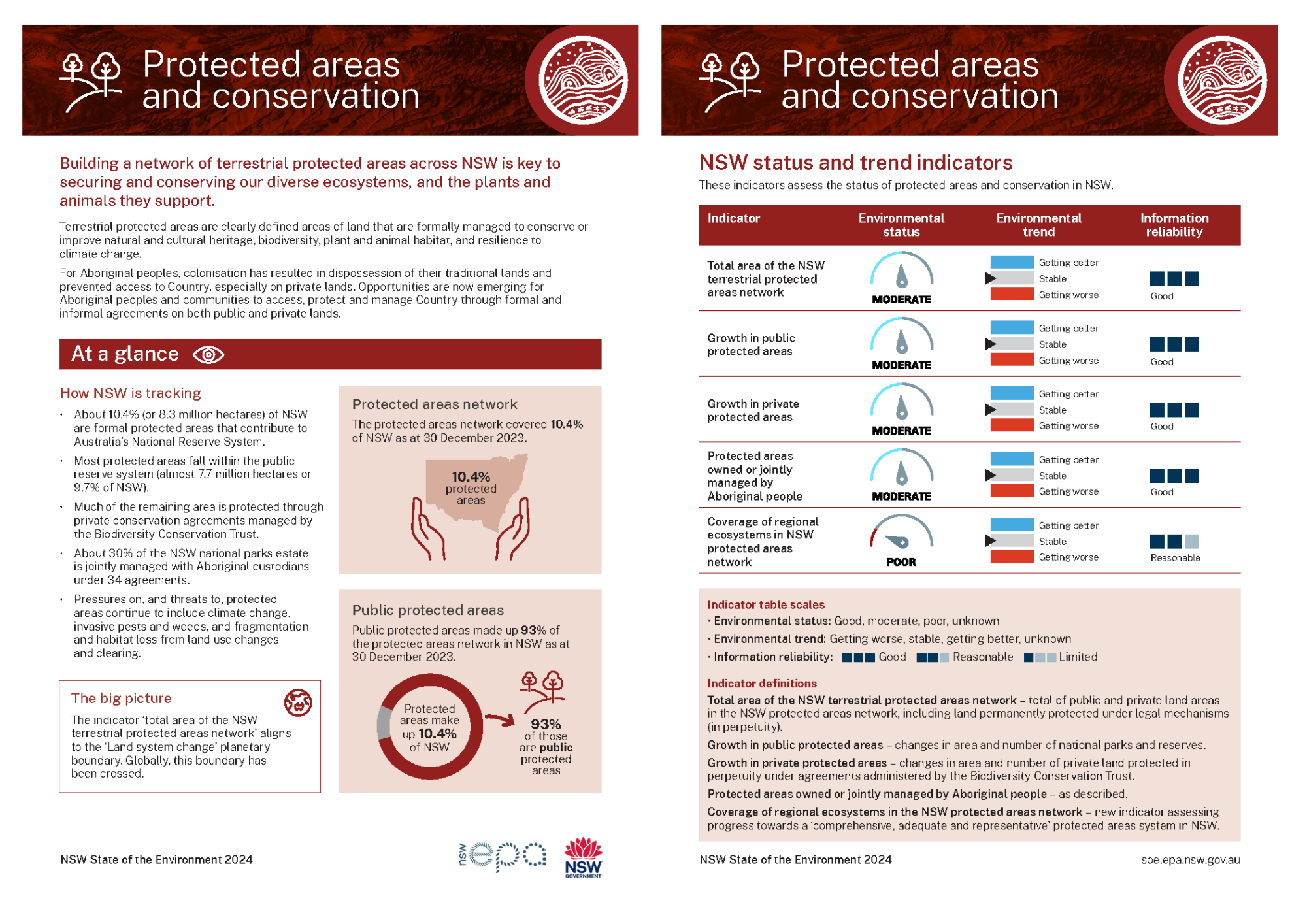

This report uses five indicators to assess the status of protected areas and conservation in NSW (see Table L2.2):

- Total area of the NSW terrestrial protected areas network measures the total of public and private land areas in the NSW protected areas network. It includes land that is permanently and securely protected under legal mechanisms (in perpetuity). There has been stable growth in the total area protected over recent years, but there is a need for this to accelerate to improve the ‘comprehensive, adequate and representative’ system in NSW, and to contribute to national targets under the Strategy for Nature 2024–2030 NRS targets for 2030. The indicator status is assessed as moderate (see the Total area of NSW protected areas system section in this topic for more information).

This indicator aligns to the ‘land system change’ planetary boundary. Globally, this boundary has been crossed. See . - Growth in public protected areas has stabilised at levels similar to the previous three years for national parks and reserves. The overall status of the indicator is assessed as moderate and the trend stable. Three large properties were purchased by the NSW Government during this period but not yet formally added to the national parks estate. When included, about 11.1% of NSW will be in public protected areas (see the Growth in national parks and reserves section in this topic for more information).

- Growth in private protected areas is assessed as moderate, showing a stable trend over the past three years in the growth of private land protected in-perpetuity under agreements administered by the BCT. Less than 1% of NSW is protected under permanent agreements on private land (see the Private protected areas in NSW section in this topic for more information).

- Protected areas owned or jointly managed by Aboriginal peoples remained stable over the past three years. The overall status of this indicator remains moderate and stable (see the Indigenous Protected Areas and joint management sections in this topic for more information).

- Coverage of regional ecosystems in the NSW protected areas network is assessed as poor. This new indicator considers current information on the progress towards a ‘comprehensive, adequate and representative’ protected areas system in NSW. While the trend is considered stable as there have been improvements in the proportion of regional ecosystems sampled at bioregion and subregion levels, progress is well below targets and there are still many ecosystems that are poorly protected, or not sampled at all, in the protected areas system (see the ‘Comprehensive, adequate and representative’ protection section in this topic for more information).

Table L2.2: Protected areas and conservation indicators

| Indicator | Environmental status | Environmental trend | Information reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total area of the NSW terrestrial protected areas network | Stable | Good | |

| Growth in public protected areas | Stable | Good | |

| Growth in private protected areas | Stable | Good | |

| Protected areas owned or jointly managed by Aboriginal peoples | Stable | Good | |

| Coverage of regional ecosystems in NSW protected areas network | Stable | Reasonable |

Notes:

Indicator table scales:

- Environmental status: Good, moderate, poor, unknown

- Environmental trend: Getting better, stable, getting worse

- Information reliability: Good, reasonable, limited.

See to learn how terms and symbols are defined.

See the page for more information about how indicators align.

Total area of NSW protected areas system

NSW has a total land area of 80,115,000 hectares. As at 31 December 2023, the protected areas network in NSW covered more than 8.3 million hectares, about 10.4% of the State (). This included:

- 7.7 million hectares of public protected areas in the national parks system and flora reserves

- 37,940 hectares of Indigenous Protected Areas

- 513,500 hectares of private protected areas administered under permanent BCT agreements

- 79,500 hectares in the Southern Mallee Reserves and eligible private property vegetation plans

- 1,270 hectares protected in the Lord Howe Island group.

The total has grown since 2018, when public protected areas were estimated as 7.2 million hectares (9%) and private protected areas as 0.4% (OEH 2018).

Public protected areas account for almost 93% of the NSW protected areas network.

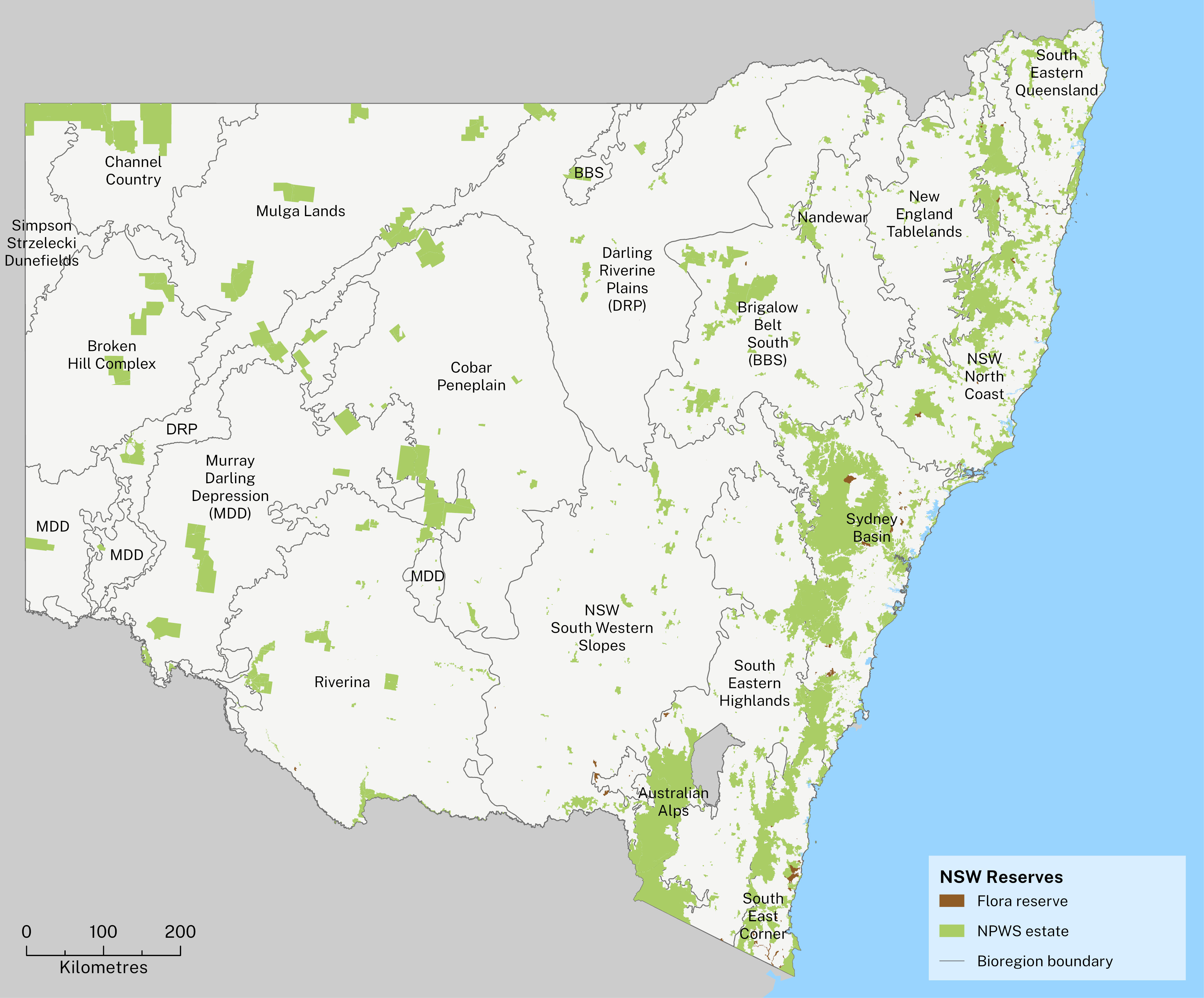

Public protected areas in NSW

Public lands that meet formal reserve standards under the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) categories are a core component of the NSW protected areas network (see Map L2.1).

The public reserve system conserves native plants and animals, a broad range of ecosystems, threatened species and habitats, and protects Aboriginal cultural and archaeological values.

National parks and reserves (national parks estate):

- 7,634 million hectares (9.5% of the State)

- includes national parks, regional parks, nature reserves, state conservation areas, karst conservation reserves, historic sites and Aboriginal areas

- established under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 and managed by the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS).

Flora reserves:

- 65,848 hectares of NSW State forest lands (almost 0.1% of the State):

- 27,478 hectares managed by the Forestry Corporation of NSW (65 reserves)

- 38,370 hectares managed by the NPWS (23 reserves)

- declared under the provisions of the Forestry Act 2012

- flora reserves under NPWS management do not form part of the national parks estate.

Map L2.1: National parks and flora reserves in NSW, December 2023

Growth in national parks and reserves

Since the NSW State of the Environment 2021, there have been 45 additions to existing NPWS parks and reserves, and 11 new NPWS reserves (Figure L2.1).

Figure L2.1: Annual additions to national parks in NSW since 2009, by number (new reserves)

The additions and new reserves during 2021–22 and 2022–23 added a total of 187,192 hectares to the national parks estate (Figure L2.2).

Figure L2.2: Annual additions to national parks in NSW since 2009, by area (ha)

The three largest additions during this time contributed about 140,000 hectares of the 187,192 hectares total.

Table L2.3 shows how the additions contribute to improvements in the ‘comprehensive, adequate and representative’ (CAR) reserve system.

Table L2.3: Contribution of additions to the CAR reserve system

| Reserve | Area (ha) | Comprehensive | Adequate | Representative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langidoon–Metford State Conservation Area | 60,416 | Broken Hill Complex C now 54% | Increasing the area under reservation for four poorly reserved and five previously unsampled, regional ecosystems | Barrier Range R now 85.7%; Barrier Range Outwash now 42.9% |

| Koonaburra National Park | 45,534 | Cobar Peneplain C now 55.6%; Murray Darling Depression C now 81.6% | Increasing the area under reservation for eight poorly reserved and four previously unsampled regional ecosystems | Barnato Downs R now 61.9%; Darling Depression R now 66.7% |

| Brindingabba National Park | 33,904 | [no change] | Increasing the area under reservation for two poorly reserved and one previously unsampled regional ecosystems | West Warrego R now 50% |

Notes:

Comprehensiveness (C) – the proportion of the range of regional ecosystems that have been sampled by the reserve system in each respective IBRA bioregion.

Adequacy – increases in the area of a regional ecosystem under reservation within an IBRA subregion.

Representativeness (R) – the proportion of the range of regional ecosystems that have been sampled by the reserve system in each respective IBRA subregions.

IBRA = Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia

Other key contributions to the growth in reserves:

- 28,322 hectares – the new Gardens of Stone State Conservation Area, in the South-Eastern Highlands and Sydney Basin bioregions

- 4,561 hectares – additions to Oxley Wild Rivers National Park, in the NSW North Coast bioregion

- 2,411hectares – additions to Culgoa National Park, in the Darling Riverine Plains and Mulga Lands bioregions.

Public land acquired but not yet formally reserved

Three further properties acquired by the NSW Government over recent years are in the process of being formally reserved (gazetted) as part of the national parks system for inclusion in the NSW protected areas network.

These properties total 596,200 hectares and contribute significantly to the CAR reserve system in the bioregions:

- 437,390 hectares – Thurloo Downs (Channel Country, Mulga Lands)

- 121,390 hectares – Avenel Station (Simpson Strzelecki Dunefields, Broken Hill Complex)

- 37,420 hectares – Comeroo Station (Mulga Lands).

Once they are added, the protected areas network will increase from 10.4% to about 11.1% of NSW.

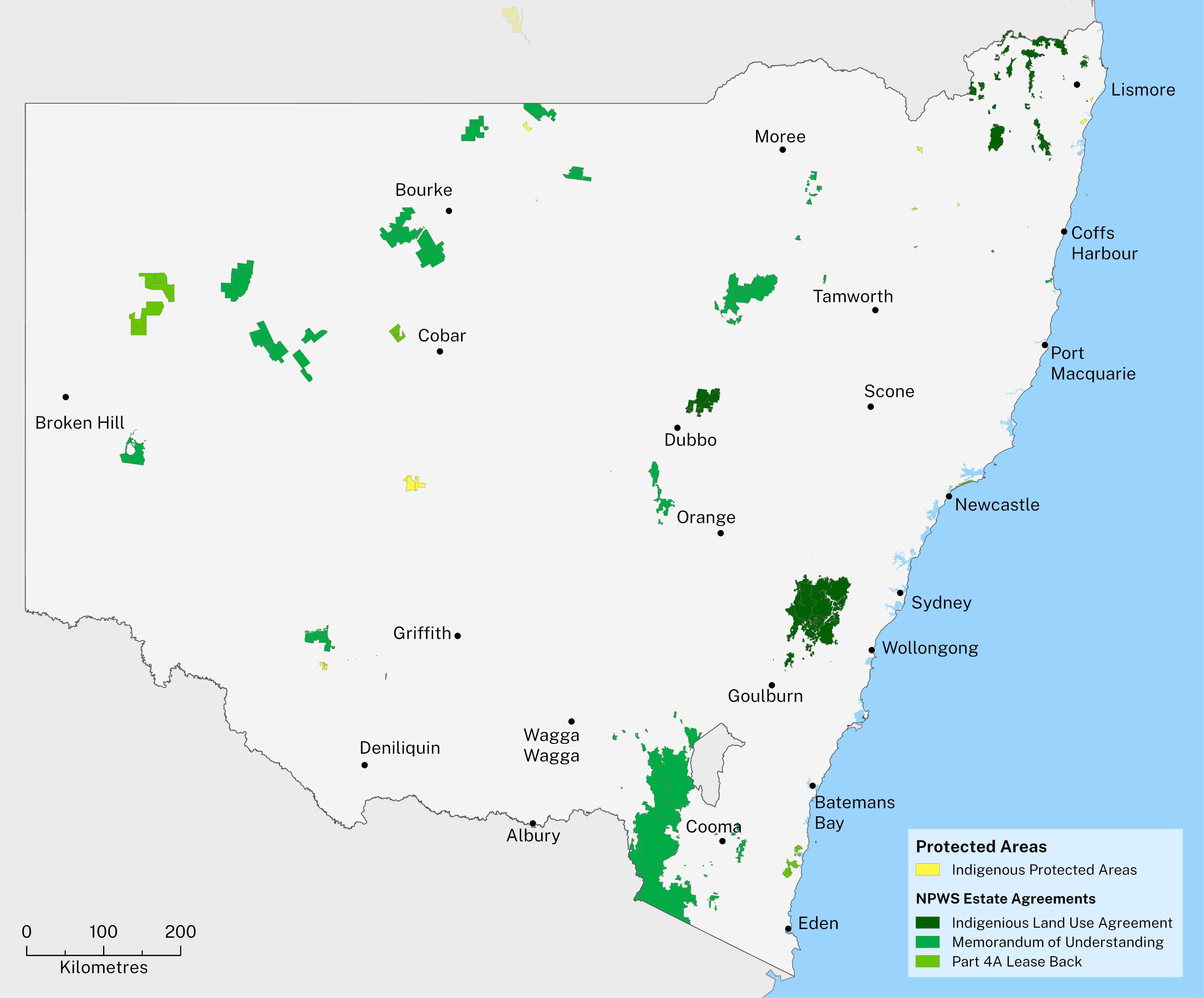

Aboriginal joint management

Aboriginal joint management in NSW formally recognises the connection of Aboriginal people to Country and facilitates involvement in management and decision-making, particularly for national parks and reserves.

At 30 June 2024 almost 2,335,000 hectares (30%) of the NSW national parks estate is managed under 34 joint management agreements with Aboriginal peoples (see Map L2.2):

- 17 Memoranda of Understanding totalling 1,572,778 hectares cover agreements between Aboriginal communities and the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water over access to and management of a park or reserve.

- 10 Indigenous Land Use Agreements totalling 588,997 hectares allow traditional owners who are native title holders or claimants to negotiate and establish a joint management partnership for a national park or reserve with the NSW Government under the Native Title Act 1993.

- 7 Aboriginal ownership and lease-back agreements totalling 173,794 hectares allow land to be returned to local Aboriginal land councils to hold on behalf of Aboriginal owners and lease back to the NSW Government under Part 4A of the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 and the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983.

Joint management arrangements also exist for other types of public lands such as State forests and Crown reserves although not all are within the protected areas network.

Aboriginal peoples hold freehold title to 2.3% of the national park estate. Following determinations in 2024, Native title has been formally recognised in more than 6% of the NSW national park estate.

Indigenous Protected Areas

Aboriginal people manage Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) for biodiversity conservation under voluntary agreements with the Australian Government.

There are 11 IPAs in NSW with a total land area of 37,939 hectares (0.5% of NSW protected areas). They are listed in Table L2.4 with their subregions and are shown in Map L2.2.

Table L2.4: Indigenous Protected Areas in NSW

| Name | Area (ha) | IBRA regions |

|---|---|---|

| Boorabee and The Willows | 2,712 | New England Tablelands |

| Brewarrina Ngemba Billabong | 261 | Darling Riverine Plains |

| Dorodong | 85 | NSW North Coast |

| Gumma | 111 | NSW North Coast |

| Mawonga | 21,987 | Cobar Peneplain, Murray Darling Depression |

| Minyumai | 2,160 | South Eastern Queensland (NSW area) |

| Ngunya Jargoon | 861 | South Eastern Queensland (NSW area) |

| Tarriwa Kurrukun | 929 | New England Tablelands |

| Toogimbie | 4,114 | Riverina |

| Wattleridge | 645 | New England Tablelands |

| Weilmoringle | 4,073 | Darling Riverine Plains, Mulga Lands |

| Total | 37,939 |

Notes:

About 21,000 hectares of land in IPAs are managed under BCT agreements.

IBRA = Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia.

Map L2.2 shows Indigenous Protected Areas in NSW and also areas where joint management agreements exist for areas of the national parks estate (but not joint management agreements with other government agencies or on private protected areas).

Map L2.2: Indigenous Protected Areas and joint management

Private protected areas in NSW

With more than 70% of the State under private ownership or Crown lease, private land conservation has the potential to play a vital role in conserving biodiversity in NSW.

As at 30 June 2024, approximately 0.8% of NSW is private land that is included in the protected areas network, this includes:

- 536,000 hectares managed under permanent agreements with the BCT

- 79,500 hectares in the Southern Mallee Reserves and in-perpetuity property vegetation plans (to conserve biodiversity).

A further 1,525,000 hectares (2% of NSW) is managed for conservation purposes under the BCT time-bound (term) or revocable agreements, but as these are not held in perpetuity, they do not contribute to the formal protected areas network.

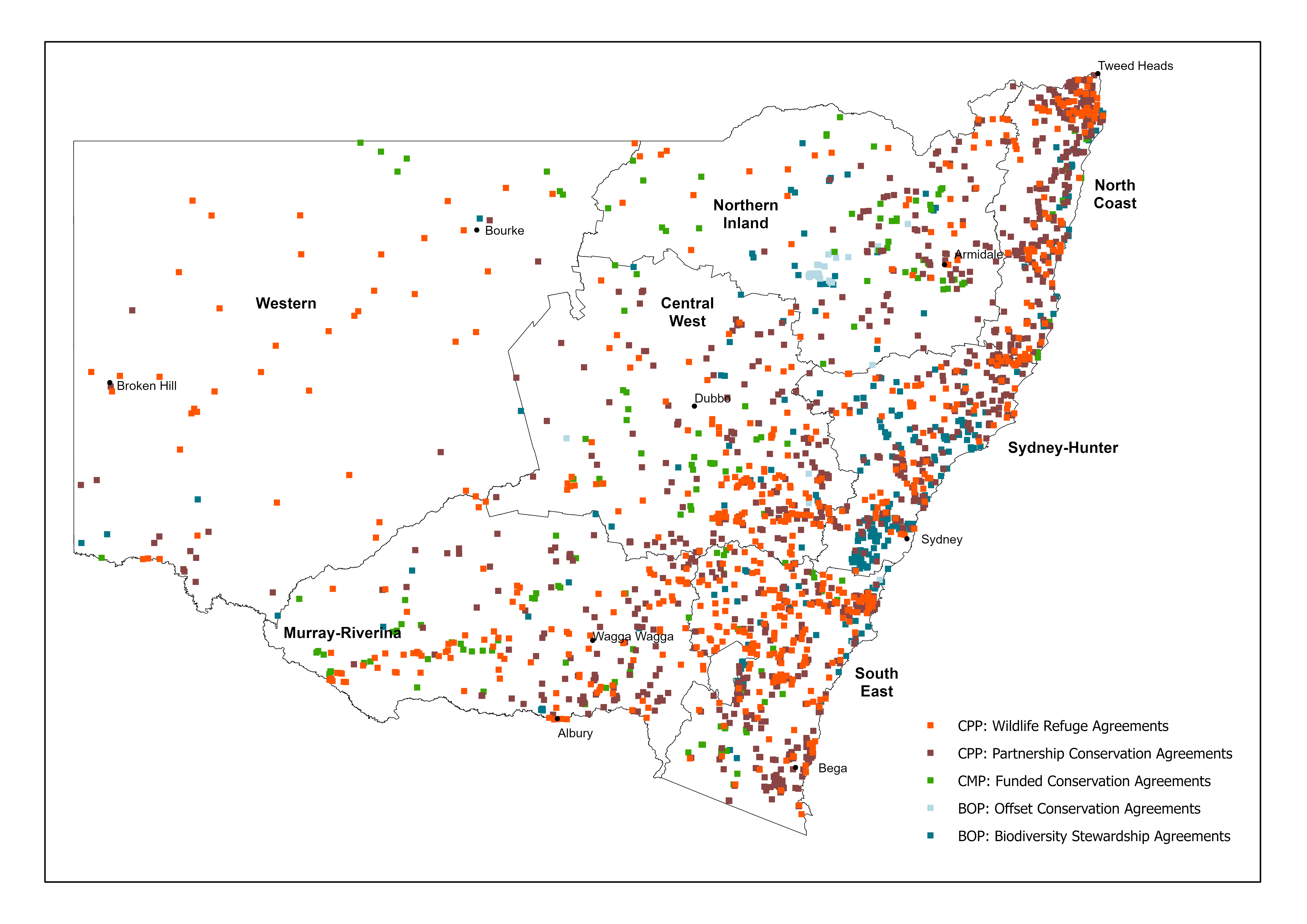

Private land conservation agreements

As at 30 June 2024, the BCT was responsible for managing 2,426 private land conservation agreements with landholders. These agreements cover more than 530,000 hectares that contribute to the NSW protected areas network and the National Reserve System (NRS).

Since 2018, 536 landholders have entered or plan to enter into a conservation agreement with the BCT, conserving private land across about 319,000 hectares (see Figure L2.3).

The BCT is investing more than $290 million to support these agreements (). This investment is split 71% for in-perpetuity (permanent) agreements and 29% for term agreements (minimum of 15 years). The permanent agreements are recognised as contributing to the formal protected areas network in NSW.

As at 30 June 2024, BCT was administering 1,662 permanent agreements representing a total of 536,310 hectares that are part of the NSW protected areas network and contribute to the NRS.

Four main categories of permanent agreements contribute to the NSW protected areas network:

- Partnership Conservation Agreements

- Funded Conservation Agreements (in perpetuity)

- Offset Conservation Agreements

- Biodiversity Stewardship Agreements.

These are shown in Figure L2.3 and Table L2.5.

Figure L2.3: Private protected areas in NSW, June 2024

A further 764 agreements administered by BCT, covering a combined total area of 1,525,716 hectares, are being managed for conservation purposes but are not part of the formal protected area network.

The breakdown of all agreements is shown in Table L2.5 and in Map L2.3.

Table L2.5: Private land conservation agreements and area in NSW (administered by the BCT)

| Agreement type | No. | Area (ha) |

|---|---|---|

| In-perpetuity Registered Property Agreements (pre-BCT) | 243 | 12,399 |

| Trust Agreements (pre-BCT) | 118 | 54,273 |

| Conservation Agreements (pre-BCT) (eligible for grants only) | 427 | 147,655 |

| Conservation Agreements (BCT) | 288 | 50,895 |

| Funded, in-perpetuity Conservation Agreements (BCT) | 129 | 143,325 |

| Offset Conservation Agreements (pre-BCT) | 56 | 10,384 |

| Offset Conservation Agreements (BCT) | 82 | 35,824 |

| Biodiversity Stewardship Agreements (pre-BCT) | 187 | 22,682 |

| Biodiversity Stewardship Agreements (BCT) | 132 | 58,872 |

| Agreements contributing to the protected area network/NRS | 1,662 | 536,310 |

| Wildlife Refuges (pre-BCT) | 646 | 1,465,212 |

| Wildlife Refuge Agreements (BCT) | 20 | 905 |

| Registered Property Agreements (pre-BCT) | 46 | 4,325 |

| Funded, term Conservation Agreements (BCT) | 52 | 55,274 |

| Other agreements (non NRS) | 764 | 1,525,716 |

All agreements managed by the BCT | 2,426 | 2,062,027 |

Notes:

The BCT commenced operating in August 2017. The table splits data on agreements into those entered into with the BCT and past agreements (‘pre-BCT’).

The distribution of private land under conservation agreements managed by the BCT is shown in Map L2.3. The map shows land under permanent agreements that contribute to the protected areas system, as well as land under non-permanent agreements.

Map L2.3: All private land conservation agreements managed by the BCT

Notes:

The map includes private land under permanent agreements that contributes to the NSW protected areas network, and other land managed for conservation under non-permanent agreements that does not contribute.

Through these agreements with the BCT, unique landscapes, threatened ecosystems and habitats for threatened native plant and animal species and ecological communities are protected and managed for conservation by private landholders, Aboriginal peoples and non-government organisations.

In 2018, the BCT met the first target under the Biodiversity Conservation Investment Strategy to protect 30 landscapes not represented, or inadequately represented, across other protected areas (). In 2024 it met its four-year business plan target to secure 200,000 hectares of private land under a BCT agreement ().

It is estimated that the current agreements protect at least 216 unique threatened species and at least 32 threatened ecological communities.

See the Private land conservation outcomes for more information.

Cultural land management practices on Country

In 2023, the Nari Nari Tribal Council signed a Conservation Agreement with the BCT to fund cultural land management practices and conservation efforts across the 55,220 hectare Gayini Conservation Area, located between Hay and Balranald, in south-western NSW.

The agreement embeds the role of traditional custodians in managing land for current and future generations and is the largest private land holding to be funded, in perpetuity, by the NSW Government. This conservation demonstrates the NSW Government’s commitment to caring for Country obligations of Aboriginal landholders

Source: BCT media release

Non-government organisations (NGOs) establish and manage land for the purpose of conservation, including areas that contribute to the protected areas network and ‘comprehensive, adequate and representative’ system in NSW. In addition to purchasing properties, some NGOs also manage other areas for restoration, protection and conservation for private landholders and government.

NGOs own or manage a total of about 106,760 hectares of land for the purpose of nature conservation and are included in CAPAD (2022) as part of the protected areas network in NSW and the NRS (). Many of these areas are managed under permanent conservation agreements administered by the BCT.

‘Comprehensive, adequate and representative’ protection

The NSW Government monitors the development of the ‘comprehensive, adequate and representative’ (CAR) system of protected areas across both public and private lands, and assesses progress against national targets.

The purpose of a CAR protected area system is to conserve samples of all regional ecosystems across the range of environments in which they occur. Protecting an ‘example’ of a regional ecosystem means that part of the ecosystem is protected under a permanent legal mechanism, for example, a national park or a permanent BCT conservation agreement. The NPWS uses the term ‘sampled’ in this context.

The following describes the CAR protected area system in NSW as of December 2023 (excluding Lord Howe Island). It includes both public and private protected areas that are permanently and securely protected for nature conservation. It also takes into consideration areas acquired for the national parks system but not yet formally gazetted.

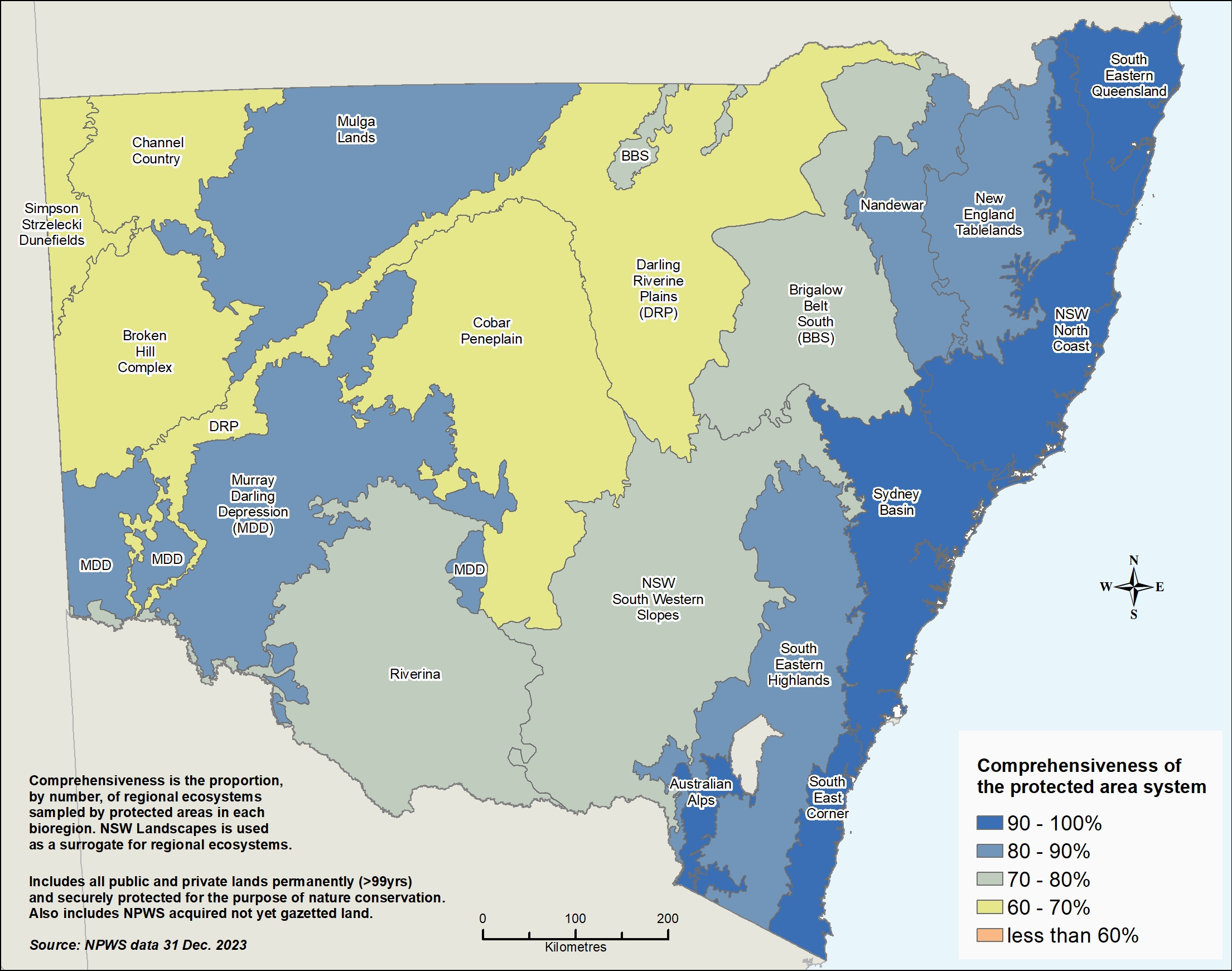

Comprehensiveness – measured at bioregion level

NSW has 794 regional ecosystems by IBRA bioregion. Of these, 653 (82%) have been sampled in the protected area system.

The comprehensiveness target of 80% (of regional ecosystems sampled) has been achieved in 10 of the 18 bioregions. The Darling Riverine Plains has the lowest score, at 61% (see Map L2.4). Of the 18 bioregions:

- 5 have a score of 90%–100% (dark blue areas)

- 5 have a score of 80%–90% (mid-blue areas)

- 3 have a score of 70%–80% (grey-green areas)

- 5 have a score of 60%–70% (yellow areas).

Map L2.4: Comprehensiveness of the public and private protected area system in NSW bioregions

Notes:

‘NSW Landscapes’ is used to represent regional ecosystems. NSW Landscapes are based on patterns in rainfall, temperature, topography (shape and features of the land), drainage patterns, geology, soil and vegetation. There are 570 NSW Landscapes (Mitchell 2002).

IBRA = Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia.

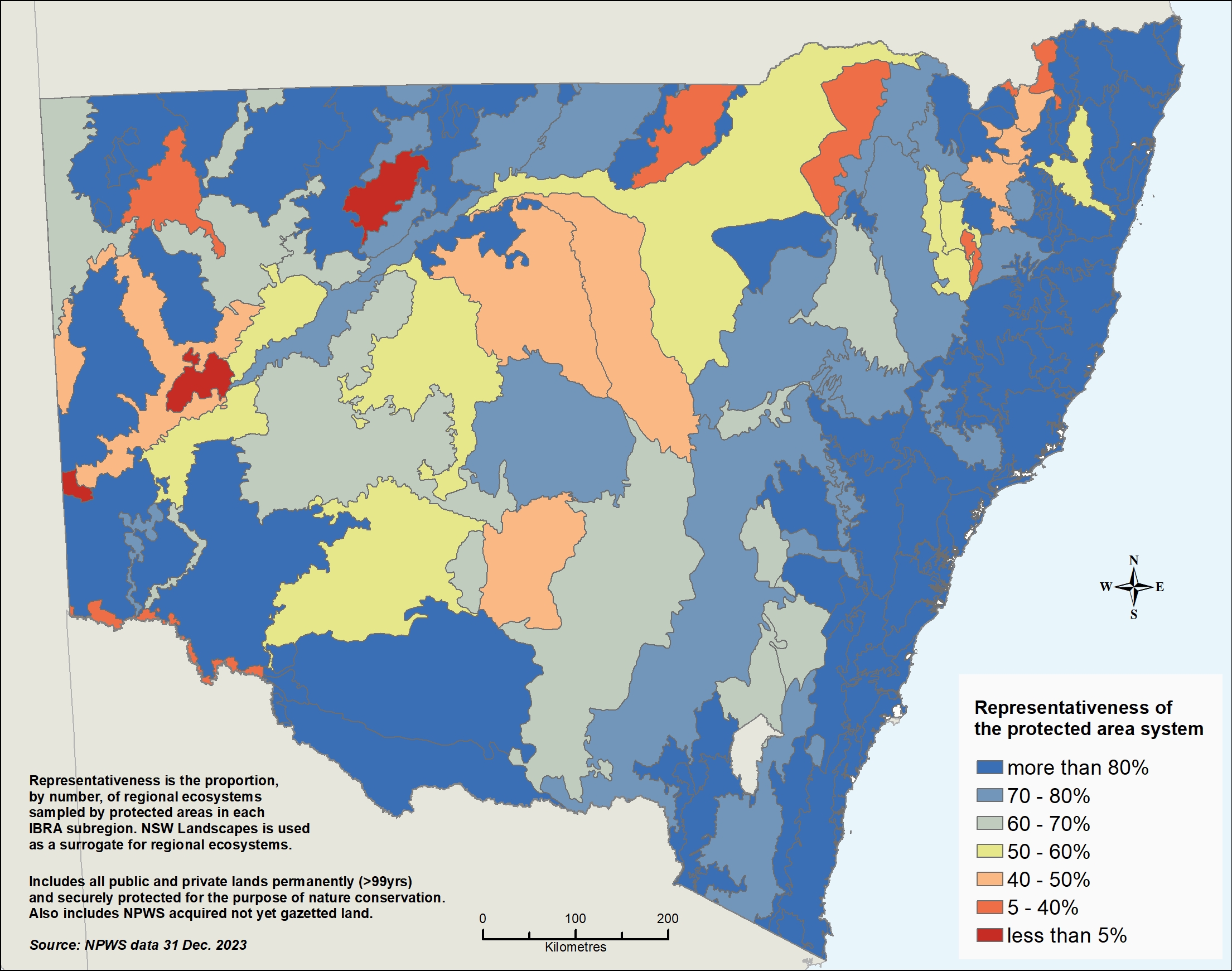

Representativeness – measured at subregion level

NSW has 1,221 regional ecosystems by IBRA subregion. Of these, 962 (79%) have been sampled in the protected area system.

The representativeness target of 80% (of regional ecosystems sampled) has been achieved in only 75 of the 131 subregions (see Map L2.5). Of these 131 subregions:

- 70 have a score of more than 80% (dark blue areas)

- 22 have a score of 70%–80% (mid-blue areas)

- 13 have a score of 60%–70% (grey-green areas)

- 8 have a score of 50%–60% (yellow areas)

- 15 have a score of less than or equal to 50% (orange areas, two shades)

- 3 have a score of 0% (red areas – shown on the map as <5%).

Map L2.5: Representativeness of the public and private protected area system in NSW IBRA subregions

Notes:

‘NSW Landscapes’ is used to represent regional ecosystems. NSW Landscapes are based on patterns in rainfall, temperature, topography (shape and features of the land), drainage patterns, geology, soil and vegetation. There are 570 NSW Landscapes (Mitchell 2002).

IBRA = Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia.

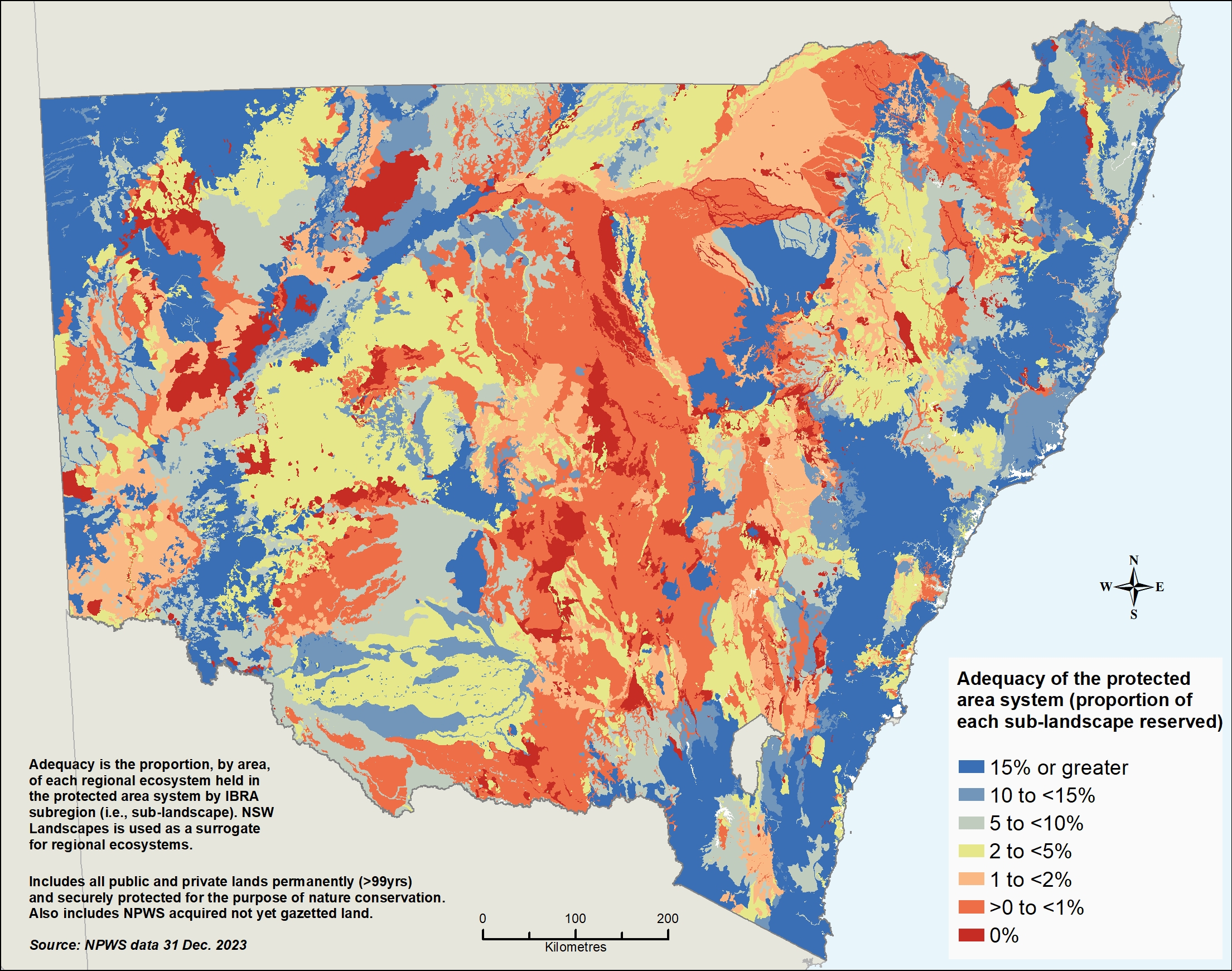

Adequacy – ecological viability of sampled regional ecosystems

Adequacy considers the viability of each sampled regional ecosystem by IBRA subregion (also known as sub-landscapes) and measures the proportion of each held within protected areas.

The adequacy target of 15% (of each sub-landscape being sampled within the protected areas system) has been achieved in 31% of sub-landscapes (see Map L2.6).

- The best protected ecosystems are those on the steep ranges of eastern NSW, parts of the coast and the Australian Alps (dark blue areas).

- Additions to the protected area system in recent years have led to substantial improvements in adequacy in the north-west of the NSW (dark blue areas).

- There remain many poorly protected ecosystems in Far Western NSW, the Northern and Central tablelands and the Western Slopes (dark orange and red areas).

- Much of the land under-represented in protected areas is heavily fragmented agricultural land, particularly in the Central West. Significant rehabilitation and revegetation is required to halt species loss.

Map L2.6: Adequacy of the public and private protected area system in NSW

Notes:

‘NSW Landscapes’ is used to represent regional ecosystems. NSW Landscapes are based on patterns in rainfall, temperature, topography (shape and features of the land), drainage patterns, geology, soil and vegetation. There are 570 NSW Landscapes (Mitchell 2002).

IBRA = Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia.

Many regional ecosystems are highly fragmented by other land uses, with remnants often too small to retain viability. Ongoing development of a CAR protected area system across a combination of public and private lands will require rehabilitation and revegetation of some areas in order to achieve targets.

The NSW Government is continuing to explore adding new, large areas of land in under-represented areas to the public reserve system when opportunities arise. Private land conservation agreements also have an important part in expanding areas under permanent conservation that contribute to the CAR protected area system.

This is particularly important given future threats from climate change, such as fire and drought, which could reduce the amount of viable land.

Other areas managed for conservation in NSW

Other areas of land are managed for conservation in NSW that do not meet the requirements for inclusion in the formal protected areas system. These include areas of State forests, Crown land and private land. Some of these areas may meet the requirements to be conserved areas under the OECM Framework.

Areas managed for conservation can supplement protected areas by providing vegetation corridors linking larger public reserves and protecting natural ecosystems that are under-represented or not present in the NSW protected areas network.

State forest management zones

Forestry Corporation of NSW manages more than 2 million hectares of State forests, including:

- 1.85 million hectares of native forest

- 34,000 hectares of hardwood plantation

- 230,000 hectares of softwood plantation.

A system of forest management zones is used to categorise management intent in State forests. Through this zoning system:

- at least 65,848 hectares of State forests is formally protected in flora reserves and contributes to the NSW protected areas network

- 279,643 hectares of State forests is protected in informal reserves

- 198,577 hectares of State forests is protected by special prescription.

These forests contribute, in varying degrees, to the protection of forest ecosystems and native species habitat and the conservation of natural and cultural values.

Native forests in remaining State forest areas are harvested in accordance with ecologically sustainable forest management principles. The Forestry Act 2012 and Integrated Forestry Operations Approvals set rules to protect environmental values during native forestry operations on public land and require harvested forests to be regrown.

See the Forestry Corporation website for further information on NSW State forests, access to maps and spatial data, and environmental reporting.

Aboriginal partnerships on State forests

Forestry Corporation partners with Aboriginal communities in a number of ways including for economic, cultural, community wellbeing and conservation.

It has Indigenous Land Use Agreements with Aboriginal groups that cover over 343,000 hectares of State forests.

See Forestry Corporation’s Aboriginal Heritage and Partnerships website for further information.

Crown lands

Crown land includes many parks, reserves, roads, cemeteries and infrastructure. Held by the NSW Government on behalf of the public under the Crown Land Management Act 2016 it is diverse and can be used in many ways.

About 38% of NSW is Crown land and includes rangelands, forests, grasslands, mountainous terrain as well as waterways, stretches of coastline and the marine estate.

Protecting environmental assets on Crown land is a key priority under Crown Land 2031: State Strategic Plan for Crown Lands (). One of the primary ways this is achieved is by reserving land for protection and conservation purposes.

As at June 2024:

- 30 Crown land sites, covering over 137,000 hectares, have established biodiversity conservation agreements in place to conserve and protect areas of high environmental value

- 749 Crown reserves that cover around 128,000 hectares have been reserved for environmental protection and conservation purposes; they are not part of the protected areas network but contribute to conservation efforts.

Greater Sydney Parklands

Greater Sydney Parklands has five estates covering over 6,000 hectares of public open space spread out across various parts of the greater metropolitan area. These include Centennial Parklands, Callan Park, Parramatta Park, Western Sydney Parklands and Fernhill Estate. The parklands are managed for the purpose of connecting communities to open spaces for recreation and enjoyment.

Established under the Greater Sydney Parklands Trust Act 2022 the parks must be managed in a way that ensures no net loss in natural environment including areas that provide an ecological function, and also areas that have been restored to a natural state or have naturalised, for example, bushland corridors or abandoned farm dams that have naturalised as wetlands.

Key aspects of the Greater Sydney Parklands estate and programs include:

- 2,000 hectare bushland corridor in Western Sydney Parklands that is, or will be restored to, natural environment. It is the most significant of the five estates and is Australia’s largest urban park

- 583 hectare Western Sydney Regional Park which is part of the NPWS estate. It is managed under the Greater Sydney Parklands Trust as part of the Western Sydney Parklands

- 7 Biobank / Biodiversity Stewardship Agreement sites under the Biodiversity Conservation Act administered by the BCT conserved in perpetuity

- small areas of vegetation managed for protection of ecological communities including parts of Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub in Centennial Parklands and plant communities on Callan Point

- various areas of recreational bushland that provide refuge and links for wildlife

- recognising and conserving Aboriginal cultural heritage and values, and establishing mutual long-term partnerships with Traditional Custodians, Local Aboriginal Land Councils and the First Nations communities of Greater Sydney.

Travelling stock reserves

Travelling stock reserves (TSRs) are authorised thoroughfares on Crown land for moving stock from one location to another. There are more than 6,500 TSRs on Crown land in NSW, covering about 2 million hectares. Almost 1.5 million hectares (75%) of the TSR network is in the Western Division of NSW.

Most land in the Western Division is held under Western lands leases, which are used for grazing, agriculture, homes and businesses. The leaseholders manage the care and control of the western TSRs. The bulk of the TSR network in the Western Division are not fenced and are grazed in the same way as the surrounding land.

Although narrow and modified by roads and farm infrastructure, such as fences and gates, many TSRs are well vegetated and in better condition than the surrounding land, particularly those in the Central and Eastern divisions.

Local Land Services (LLS) controls and manages about 530,000 hectares of TSR land, concentrated mainly in the Central and Eastern divisions (see Table L2.6).

The TSR network contains areas of high environmental value, including habitat for threatened plant and animal species and ecological communities. It provides habitat connectivity through often highly cleared and fragmented landscapes.

Table L2.6: Travelling stock reserves in NSW managed by Local Land Services

| Region | Area (hectares) | Bioregion (hectares) | % of bioregion in a TSR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australian Alps | 272 | 464,298 | 0.06 |

| Brigalow Belt South | 63,449 | 5,624,738 | 1.13 |

| Broken Hill Complex | 28,708 | 3,763,318 | 0.76 |

| Channel Country | 9,280 | 2,340,662 | 0.40 |

| Cobar Peneplain | 45,776 | 7,377,221 | 0.62 |

| Darling Riverine Plains | 133,067 | 9,419,258 | 1.41 |

| Mulga Lands | 28,311 | 6,591,283 | 0.43 |

| Murray Darling Depression | 57,040 | 7,935,881 | 0.72 |

| Nandewar | 20,847 | 2,074,882 | 1.00 |

| New England Tableland | 27,863 | 2,860,298 | 0.97 |

| NSW North Coast | 8,753 | 3,962,538 | 0.22 |

| NSW South-Western Slopes | 48,582 | 8,103,373 | 0.60 |

| Riverina | 92,359 | 7,022,692 | 1.32 |

| Simpson–Strzelecki Dunefields | 0 | 1,095,797 | 0.00 |

| South-East Corner | 2 | 1,153,601 | 0.00 |

| South-Eastern Highlands | 6,474 | 4,989,020 | 0.13 |

| South-Eastern Queensland (NSW area) | 4,734 | 1,647,041 | 0.29 |

| Sydney Basin | 2,091 | 3,573,566 | 0.06 |

| Total and average percentage | 577,606 | 79,999,467 | 0.72 |

See the TSR State Classification Map for reserves managed by LLS.

About 335,000 hectares of travelling stock reserves managed by LLS are considered to be of high value. This means that they are actively managed to maintain or improve biodiversity conservation or cultural values. These may be considered for inclusion as National Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures in the conserved areas network for NSW.

Further information on the conservation value of NSW travelling stock reserves can be found on the NSW Government’s SEED database and on the LLS website.

Pressures and impacts

Lack of custodian access to Country

Interruptions to cultural landscapes

Cultural landscapes reflect the traditional relationships Aboriginal peoples have with different parts of Country. From a cultural heritage perspective they are important as they bring together living patterns, land management, traditional knowledge and dreamtime stories in the land. Cultural landscapes have been interrupted and fragmented by loss of access to Country for Aboriginal peoples due to land ownership and land use changes across NSW.

Land use and human activities

Reduced landscape connectivity

Land use changes, such as development for housing or clearing for agriculture and infrastructure, can make maintaining habitat connectivity difficult. Improving connectivity is particularly important in over-cleared landscapes where ecosystems may be under significant pressure owing to a history of clearing and fragmentation.

Habitat and species isolation can occur when there are limited vegetation corridors or natural areas between reserves and other key habitats. This can impede dispersal of plants and movement of animals across landscapes, reducing reproduction and genetic diversity.

Visitor use and infrastructure

Growing levels of visitation and associated infrastructure may increase pressures on the environmental values of public protected areas if not appropriately managed.

Fostering public appreciation and enjoyment of nature, cultural heritage and conservation is a key objective in managing the public reserve system. Increased public appreciation and enjoyment in turn fosters greater care and stewardship of parks.

National parks remain important to the NSW public, as shown by an increase in the percentage of surveyed people visiting them since 2015 (see Table L2.7).

Table L2.7: Survey of national park visits in the last 12 months

| Response | 2015 (%) | 2022 (%) | 2023 (%) | 2024 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 5 times | 47 | 48 | 55 | 56 |

| 6 to 12 times | 13 | 14 | 11 | 12 |

| More than 12 times | 10 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| 0 times | 30 | 26 | 24 | 23 |

| Don’t know / can’t recall | 0 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Sample size (n) | 2,000 | 1,901 | 2,063 | 2,060 |

Notes:

Question: In the last 12 months how many times have you visited a National Park?

An increase in visitation must be balanced with conservation objectives and ecologically sustainable forest management principles.

Illegal activities

As at May 2021, the most widely reported illegal activities threatening NSW national parks were:

- damage caused by clearing and firewood collection

- dumping of waste

- antisocial behaviour

- arson

- collecting of native plants.

These activities reduce natural and cultural heritage values and the capacity of the NPWS to maintain these values.

Illegal activities threaten visitors’ enjoyment and safety, harm native animals and plants, and damage cultural heritage sites and park assets.

Invasive species and diseases

Invasive species and diseases cause some of the most significant problems for native plants and animals and threatens biodiversity. As such, their impact and management are high priorities for public and private protected areas and other land managed for conservation.

See the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 for a full list of invasive plants and animals.

Invasive species and diseases affect threatened species and ecological communities by damaging habitats and outcompeting native plants and animals for resources. They can also damage community infrastructure and public amenity and affect Aboriginal cultural relics, such as rock engravings and grinding grooves.

The most significant widespread invasive animals threatening environmental values in reserves include foxes, feral cats, feral goats, rabbits, deer, wild horses and feral pigs.

See the topic for more information.

Of the more than 350 invasive plant species affecting environmental values in NSW in April 2021, the following were some of the most pervasive in reserves:

- bitou bush (Chrysanthemoides monilifera rotundata)

- lantana (Lantana)

- African olive (Olea europaea cuspidata)

- Scotch broom (Cytisus scoparius scoparius)

- introduced perennial grasses, such as serrated tussock (Nassella trichotoma)

- exotic vines, such as Madeira vine (Anredera cordifolia).

See the topic for more information.

Pathogens and diseases

Pathogens are organisms, such as viruses, bacteria and fungi, that cause disease. They threaten the integrity of ecosystems, animals and plants within protected areas.

The NSW Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 and the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 identify pathogens that are considered key threatening processes, including:

- Myrtle rust (Puccinia psidii) – a fungal disease which affects plants

- root-rot fungus (Phytophthora cinnamomi) – a water mould.

See the Plants topic for more information.

Climate change

The effects of climate change are already being felt, particularly in protected areas. Effects include:

- loss of plants, animals and their communities, restriction of their ranges and reduced capacity to adapt to climate change

- increased risk of extreme weather events, including extreme rainfall and severe fire weather

- increased impacts on coastal reserves from sea level rise

- increased weed invasion and spread due to changes in temperature and rainfall

- loss of tangible and intangible Aboriginal cultural heritage.

While it is likely that all natural systems will be affected by climate change, some systems particularly likely to be affected include:

- rainforests

- subalpine habitats

- saltmarshes

- freshwater lagoons

- sand dunes

- threatened seabird habitats

- water-dependent ecosystems

- threatened and endangered species

- ecological communities.

Fire management

Inadequate bushfire management exacerbates the threats to biodiversity.

Over the past 50 years, the risks associated with managing bushfires across the landscape, particularly in forested areas, have been steadily rising owing to a range of factors, including climate change. As temperatures increase, so too do the number of severe fire weather days and the length of the fire season over much of NSW.

See the topic for more information.

Protected areas have been particularly affected by extreme climate and weather in recent years. For example, the NPWS estimated that 2.7 million hectares of the NSW national park estate (about 38%) was impacted during the Black Summer bushfires in 2019–20.

Improved risk mitigation and hazard reduction burning practices can reduce the risks to and impacts on biodiversity.

The Final Report of the NSW Bushfire Inquiry (July 2020) recommended increasing the use of traditional Aboriginal burning practices (recommendations 25 and 26).

In response, the NSW Government has committed to adopting cultural burning as one component of a broader practice of traditional Aboriginal land management and recognising it as an important cultural practice, not simply another technique of hazard reduction burning.

Responses

Aboriginal involvement in conservation

The NSW Government increasingly recognises Aboriginal peoples’ obligations to care for Country and has been introducing and expanding programs that partner with Aboriginal peoples in land and water conservation and management. See the topic for more information.

Aboriginal joint management of NSW national parks

The NPWS is developing a new model for joint management of the State’s national parks and reserves to support the expansion of joint management under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974.

Joint management involves Aboriginal peoples who have a cultural association with a national park or reserve being involved in, or advising on, its management. It enables them to have input to conservation measures including invasive animal and weed management and cultural fire management.

The new model proposes the continued management of national parks for the public to enjoy while enhancing conservation initiatives and visitor experiences through greater involvement of Aboriginal peoples. It is being developed through engagement with Aboriginal communities, the NSW Coalition of Aboriginal Peak Organisations, national park stakeholder groups and the public.

Cultural fire management

Cultural Burning is an integral part of connection to Country for Aboriginal communities. Australia’s native plants and animals evolved to live with fire, and many species rely on small, managed fires as part of their natural lifecycle.

The use of Cultural Fire management practices in NSW has increased in recent years across public and private lands.

The NSW Cultural Fire Management Strategy, currently under development, will help guide NSW Government departments to support Aboriginal communities in cultural fire management activities.

See the topic for more information.

In response to the Statutory Review of the Local Land Services Act 2013, Local Land Services (LLS) is working with the Cultural Fire Management Unit to explore potential opportunities with Aboriginal peoples and landowners to facilitate Cultural Fire management across differing land tenures. The focus is to develop respectful ways to work with Aboriginal stakeholders to expand the use of Cultural Fire management and to develop community-led monitoring and evaluation indicators.

Forestry Corporation of NSW is co-funding a $3 million partnership cultural burning program looking at the use cultural burns to reduce bushfire risk on State forests. The project, part funded through the Australian Government Disaster Ready Fund, is establishing partnerships with Aboriginal communities and organisations to reduce the risk, harm and severity of major and catastrophic bushfire events and other natural hazards. It involves traditional mapping and cultural knowledge, Aboriginal and other stakeholder co-design, Aboriginal employment, contracting and skills development.

Crown Lands (within the Department of Planning, Housing and Infrastructure) has a Cultural Burn Program that facilitates and supports the Aboriginal community, including Traditional Owners and Local Aboriginal Land Councils, to undertake cultural fire management on Crown land. The program aims to:

- provide an opportunity for Aboriginal communities to further develop and enhance their skills in caring for Country, including opportunities to be reimbursed for their time and knowledge

- partner with Traditional Owners across NSW to support and undertake cultural fire management

- facilitate Cultural Fire management with the objective of getting community out onto Country, which contributes to a wide-ranging benefits.

Aboriginal peoples and travelling stock reserves

It is believed that TSRs follow pathways used traditionally by Aboriginal peoples to travel across country. Many are next to or follow tracks and rivers. TSRs are important to Aboriginal peoples for access and connection to Country, cultural practices and cultural heritage protection.

Many TSRs are the subject of Aboriginal land claims (NSW Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983) or Native Title determination (Commonwealth Native Title Act 1993). These claims may eventually lead to a transfer of land or management agreements with Aboriginal peoples ().

LLS is investigating ways to better enable traditional land management practices to heal Country and restore endemic natural systems, especially native vegetation and ecosystems, through the use of traditional knowledge and contemporary approaches to propagation and planting. One example is an Aboriginal cultural burn at Top Gobarralong.

Expansion of protected and conserved areas

The Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework calls for the conservation of at least 30% of land and sea areas, globally, by 2030. As a signatory, the Australian Government has set a 30 by 30 target to be delivered through a combination of formally protected areas and other conservation measures.

The NSW Government has agreed to implement measures and improve current programs, including the growth of public and private protected areas, to support efforts to meet the national target.

Conserved areas network

In June 2024, environment ministers in Australia agreed to the National Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (OECMs) Framework to enable the recognition of high biodiversity value land-based ‘conserved areas’. The purpose being to provide conservation in places where formal protection within the protected areas network is not possible, appropriate or supported.

The aim is for a conserved areas network to complement the protected areas network and contribute to achieving the national target to protect 30% of land by 2030. Future assessment of progress towards a CAR protected areas system is expected to include conserved areas when they have been defined and implemented for NSW.

Increasing and conserving koala habitat

The NSW Koala Strategy 2021–26 aims to double the number of koalas in NSW by 2050. It sets out actions and targets to work towards protecting, restoring and conserving koala habitat, improving koala health and safety, expanding our knowledge of them, and supporting communities to conserve them.

More than 15,000 hectares of koala habitat has been purchased, across 17 parcels of land, for inclusion in the national parks system. This meets the target set in the strategy.

From July 2021 to June 2024, the BCT entered into 161 new conservation agreements with private landholders, permanently protecting 10,838 hectares of koala habitat. This exceeded the 7,000 hectares five-year target set under the strategy.

Private land conservation support

Biodiversity Conservation Investment Strategy

The Biodiversity Conservation Investment Strategy guides conservation investments to advance a CAR protected area system. It targets funding to areas that have not met the CAR targets, or that have met the targets but require in-perpetuity agreements.

Biodiversity Conservation Trust

Through its programs, the BCT is investing more than $290 million to deliver private land conservation outcomes and are seeking partnerships to accelerate their efforts to protect, connect and restore biodiversity in NSW.

Investment in private land conservation is essential for meeting national and international obligations for the growth of protected areas and the long-term conservation of biodiversity.

This investment is split 71% for in-perpetuity (permanent) agreements and 29% for term agreements (minimum of 15 years). Many unique landscapes, threatened ecosystems and habitats for our threatened native plant and animal species, are now protected and are being managed by private landholders.

Biodiversity Offsets Scheme

Legislated under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, the Biodiversity Offsets Scheme provides a mechanism to avoid, minimise and offset the impacts of development, and some types of clearing, on biodiversity in NSW.

Government initiatives in response to legislative reviews

In July 2024, in its response to the reviews of the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 and native vegetation provisions of the Local Land Services Act 2016, the NSW plan for nature, the NSW Government proposed actions to expand private land conservation initiatives, including:

- strengthening the BCT’s private land conservation program

- introducing stronger private land conservation agreements that protect sites of high biodiversity value from incompatible land uses

- broadening private land conservation agreements to recognise and protect Aboriginal cultural values and traditional ecological knowledge

- improving the management, funding and reporting of private land conservation agreements and biodiversity credits.

NSW plan for nature

In accordance with the NSW plan for nature, LLS is supporting landholders to evaluate opportunities in environmental and natural capital markets, some of which may encourage biodiversity conservation.

Support and incentives also help landholders to implement land management practices that benefit biodiversity, threatened species, soils and waterways. Actions include preserving and enhancing natural habitats and provision of technical advice on how to manage lands to improve biodiversity values.

Travelling stock reserves for biodiversity credit generation

LLS is responsible for the care, control and management of about 30% of travelling stock reserves (TSRs) in NSW, covering around than 578,000 hectares. Some of the TSRs are underused for stock movement and recreation purposes, have significant biodiversity values and contain priority vegetation communities currently sought under the Credit Supply Taskforce.

There is potential for TSRs to generate biodiversity credits under the Biodiversity Offset Scheme and provide a source of income that can be used to conserve and improve the biodiversity value of these sites.

The Credit Supply Taskforce and LLS have developed a pilot project to investigate the credit potential of a selection of TSRs, starting with sites in the Central West region. The Credit Supply Taskforce has engaged accredited assessors to calculate the number and type of biodiversity credits that could be generated on each TSR, determine whether these credits are currently in demand and assess the feasibility of each site as a Biodiversity Stewardship Agreement (BSA) site.

Establishment of BSA’s over parts of LLS’s TSR network would enable better management of the environmental and cultural values of these sites, such as improved fire management, invasive animals and weed control, fencing, replanting, facilitation of natural regeneration of native vegetation and conservation of significant sites and places.

Non-government contributors to conservation

In addition to government initiatives and support, non-government organisations (NGOs) and land trusts, and corporate and philanthropic investment are contributing to the increase in private protected areas and conservation efforts in NSW. They work individually and also through partnerships and in cooperation with other organisations, Aboriginal landholders and communities, individual landholders and government agencies.

An example of organised collaboration is the emergence over the past decade of the Australian Land Conservation Alliance, a member–based national body representing organisations that work to conserve, manage and restore nature on private land. Members include NGOs and land trusts operating in NSW, environment groups and natural resource managers.

Protected areas management

Appropriate management of existing and emerging invasive animals, weeds and diseases before they start to threaten native plants, animals, ecosystems and cultural sites is crucial to effective conservation.

Invasive animal and weed management

In NSW weed management is prioritised based on risk as evaluated through the NSW Weeds Risk Management system. The risk for each weed is assessed based on the potential impacts if it becomes more established and/or more widespread. Regional Strategic Weed Management Plans also use risk to prioritise weed management in the 11 Local Land Services (LLS) regions.

See the topic for more information.

LLS coordinates and leads programs to control invasive animals. Its coverage expanded from 46.8 million hectares in 2021 to 54.7 million hectares in 2024. Invasive animal control programs include ground and aerial baiting, trapping and aerial ground shooting. In the same period, LLS also facilitated weed management of 141,100 hectares of private rural land for improved biosecurity, biodiversity outcomes and agricultural productivity.

Crown Lands invests in biosecurity and control of invasive species. The Crown Reserves Improvement Fund Program provides financial support for the maintenance, improvement or development of Crown reserves. It funds projects and works that enhance environmental assets by supporting conservation initiatives and the control of invasive animals and weeds. In 2023–24, it invested about $4 million in invasive animals and weed control.

To support this work, a new spatial database, developed by Crown Lands for planning and recording work to meet its biosecurity duty under the Biosecurity Act 2015, came into use in 2023–24. It enables Crown Lands staff to spatially view invasive animal and weed control, helping to align efforts with other land managers where statewide priorities are identified and shared.

Controlling invasive animals in national parks

NPWS has been delivering record levels of feral animal control since 2019–20, including the largest aerial shooting program in its history. The NPWS aerial shooting and baiting programs have been increasing since 2020 to address invasive animals, including foxes, feral cats, wild dogs, goats, pigs, feral horses and deer. These efforts:

- mean there is more habitat and food available for native animals

- prevent the spread of diseases that native animals have no resistance to

- protect threatened species, native plants, animals, landscapes and catchment values

- limit the impact of invasive animals on neighbouring properties.

Invasive predator-free areas

The NPWS is establishing a network of predator-free areas within NSW national parks. At the time of writing, the network contains ten sites where locally extinct and threatened native mammals are being reintroduced and ecosystem functions are being restored.

Protected areas monitoring

Ecological monitoring on private land

The Ecological Monitoring Module has been established under the BCT Monitoring, Evaluation, Reporting Framework with the purpose of measuring change in biodiversity across all types of private land conservation agreements administered by the BCT.

More than 1,500 baseline monitoring plots have been established to date at both agreement and control sites. Data will be used in program evaluation, reporting and improvement, as well as in the evaluation and adaptive management of agreements.

The BCT also has established baseline monitoring on legacy biobanking sites where no monitoring was in place.

Monitoring of NSW national parks and reserves

The NPWS Ecological Health Performance Scorecards program is an initiative that aims to improve the ecological health of NSW national parks by providing data-based metrics to track key ecological indicators, informing park management decision-making and securing improved conservation outcomes.

Scorecards will be published annually, reporting on ecological health, management activities and expenditure, and enabling adaptive management of NSW national parks. This initiative will enable the NPWS, for the first time in its history, to systematically collect and apply the critical information required to design and deliver effective park management.

The pilot program measures the health of our national parks in eight sites across NSW by monitoring environmental indicators related to:

- the health of native plants and animals

- threats to ecological health, such as invasive animals and weeds

- important ecological processes, such as soil chemistry and water quality

- fire patterns.

Each site represents a major ecosystem within the national park estate. Most of the scorecards should become available in 2025.

See the and topics for more information of monitoring of specific species on the NSW national parks estate.

Monitoring programs on State forests

Forestry Corporation of NSW is undertaking a biodiversity monitoring program across eastern NSW state forests in collaboration with the NSW Natural Resources Commission. The purpose is to evaluate the wildlife protection effectiveness of the Coastal Integrated Forestry Operations Approval.

This complements long-standing, species-specific monitoring for animals such as the southern brown bandicoot, smoky mouse and large forest owls. The program tracks occupancy trends in focal species such as koalas, gliders and ground mammals through sightings and interactions across 600 baited sites using remote cameras and sound recorders.

Call recognisers developed by the NSW Department of Primary Industry and Regional Development detect species like koalas, owls, gliders and glossy black-cockatoos, with more in progress. Seasonal surveys capture variations, such as powerful owls being vocal in autumn and koalas in spring. Validated data includes images of bandicoots with babies, spotted-tail quolls and detections of species like sugar gliders and glossy black-cockatoos.

Climate change adaptation and Net Zero

The NSW Climate Change Adaptation Strategy, released in 2022, lays out the NSW Government’s approach to making the State more resilient and adapted to climate change. It is supported by the NSW Climate Change Adaptation Action Plan 2025-2029 which complements other major government initiatives including the State Disaster Mitigation Plan.

The strategy and plan build on the principles of previous policies and plans, such as the NSW Climate Change Policy Framework (PDF 2.4MB) of 2016 and the Net Zero Plan Stage 1: 2020–2030 of 2020.

The topic provides an update on progress towards the plan.

Future opportunities

Comprehensive and transparent information

The Collaborative Australian Protected Areas Database, maintained by the Australian Government, collates data on protected areas on a state and national basis. It is updated every two years.

There is a need to bring together information and data on the NSW protected area network and make it publicly accessible and clear. Doing so would require:

- data on public, private, Aboriginal and other areas included in the protected and conserved areas networks

- a dashboard to show progress against key targets and progress against CAR targets

- comprehensive and individual maps on the protected areas network and bioregion CAR attributes

- coordination and collation through one NSW Government department or agency.

Information related to areas protected or conserved in NSW under both NSW and Commonwealth legislation and mechanisms, should be reported on the dashboard. While SEED (the Central Resource for Sharing and Enabling Environmental Data in NSW) is an appropriate repository for access by government agencies, academics and scientists, it is not an appropriate information, communication and reporting portal for a broader audience.

It would be beneficial if information on both terrestrial protected (and conserved) areas and marine protected areas were made available through the same reporting mechanism.

Strategic direction

In 2023, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) noted that the creation of new protected areas; the expansion of existing ones; maintaining and establishing conservation corridors that connect these areas; and better management of them, are the most effective policy tools to address the twin crises of biodiversity loss and climate change.

New protected areas, the expansion of existing ones and support for OECMs (conserved areas) can target places where carbon richness and high biodiversity overlap to create ‘carbon stabilization’ areas ().

With substantial areas of NSW under private ownership, it is important that the NSW Government, in consultation with Australian Government, further boosts permanent private land conservation, filling gaps in the public protected areas system. Effectively progressing the introduction of conserved areas is one step to help meet the national ‘30 by 30’ target and NSW’s progression towards net zero by 2050, but further initiatives may well be needed.

References

NPWS unpub., Data on protected areas in NSW (unpublished), National Parks and Wildlife Service

Image source and description

Topic imagePaakantji, Ngyiampaa and Mutthi Mutthi lands– Mungo National Park. Photo credit: Hao Li/DCCEEW (n.d.).Banner imageTopic image sits above Butjin Wanggal Dilly Bag Dance by Worimi artist Gerard Black. It uses symbolism to display an interconnected web and represents the interconnectedness between people and the environment.

Image source and description

Topic imagePaakantji, Ngyiampaa and Mutthi Mutthi lands– Mungo National Park. Photo credit: Hao Li/DCCEEW (n.d.).Banner imageTopic image sits above Butjin Wanggal Dilly Bag Dance by Worimi artist Gerard Black. It uses symbolism to display an interconnected web and represents the interconnectedness between people and the environment.