Summary

The NSW environment and community face significant challenges from invasive pests and weeds, and introduced pathogens. Invasive species are widespread across land, freshwater and marine environments in NSW. Ongoing resources will need to be available to manage new outbreaks and biosecurity risks.

Many invasive species have been in NSW for a long time and most parts of NSW are affected by weeds that harm native species, ecosystems and agriculture. Once established, they are difficult to control effectively and remain a significant environmental and economic issue.

Pest animals and weeds are identified as a threat to over 70% of threatened species under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. In NSW, weeds account for $1.8 billion a year in lost production and control costs while the estimated annual economic loss to the NSW economy from the impact of pest animals in NSW is estimated to be more than $170 million including the cost of management actions.

Many native animals have become threatened or extinct from being preyed on or out-competed by introduced animals such as cats and foxes. Grazing and browsing by introduced herbivores such as rabbits, goats and deer has led to habitat degradation and a decline in native vegetation diversity and productivity. Pest fish threaten native fish species and aquatic ecosystems, with carp present across most of the Murray–Darling Basin.

New and emerging invasive species pose an additional threat and burden to the environment and the wellbeing of our communities. Invasive pathogens are an emerging threat to both biodiversity and agriculture.

The NSW Invasive Species Plan 2018–2021 (DPI 2018a) sets goals, strategies and guidelines to exclude, eradicate or manage invasive species. These will be monitored and reported on in a new NSW State of Biosecurity Reporting framework.

Related topics: Threatened Species | Native Fauna | Native Vegetation | River Health

NSW indicators

| Indicator and status | Environmental trend |

Information reliability |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of new invasive species detected |

|

Stable | ✔✔ |

| Spread of emerging invasive species |

|

Stable | ✔✔ |

| Impact of widespread invasive species |

|

Stabilising | ✔✔ |

Notes:

Terms and symbols used above are defined in How to use this report.

Context

Invasive species have been implicated in the decline or extinction of many native plants and animals in land-based and water-based ecosystems. See the Threatened Species, Native Fauna and Native Vegetation topics for more information.

Australian native plants and animals have co-evolved over millions of years. When invasive species are introduced, they can have major negative impacts because native species have not evolved ways to deal with them. Invasive species harm native species and the natural environment in NSW by:

- eating or infecting them

- competing with them for resources

- modifying and degrading habitats

- transmitting disease

- reducing native biodiversity

- disrupting ecosystem processes.

Introduced marine species can threaten marine environments and animals and the industries and communities they support. Fresh water fish, such as carp and tilapia, out-compete native species, disrupt ecosystems and reduce water quality and native biodiversity.

In NSW, many invasive pest animals and weeds were introduced intentionally before people realised how damaging they were to native species and livelihood. Examples include:

- pigs and goats, and various crops, for agricultural production

- pets such as cats, and garden plants

- foxes introduced for fox-hunting

- plants used for erosion control such as bitou bush used for sand dune stabilisation.

- nuisance insect control, such as Eastern Gambusia introduced for mosquito control in the early 20th century.

New invasive species in NSW have been introduced inadvertently in vehicles, equipment, packing material, soil or garden refuse; or through ocean shipping. Emerging threats include:

- pest birds such as Indian mynas

- introduced turtles such as red-eared slider turtles

- insects such as fire ants and yellow crazy ants.

In this report, estimated costs to the economy do not include environmental and social impacts but do include the costs of control in environmental areas.

Definitions of invasive species

Pest animal: an animal (usually non-native) having, or with potential to have, an adverse environmental, economic, or social impact on native plants and animals

Weed: a non-native plant or native plant removed from its natural habitat that has the risk of negative environmental, economic, or social impacts

Invasive species: A general term to include pest animals, weeds or other organisms such as pathogens that are introduced to places outside their native ranges, where they negatively affect local ecosystems and species (IUCN 2014).

Indicators for future reporting

This report adopts similar indicators to previous State of the Environment reports. Development of new indicators to more effectively identify the impacts of invasive species and the effectiveness of management practices were published in the NSW State of Biosecurity Report (DPI 2018b). Following the first publication, a report will be published every four years. Future reports will:

- check progress

- refine the indicators

- report on changes in distribution and population size of invasive species in NSW

- report on the effectiveness of stakeholder and government programs.

Future NSW State of the Environment reports may adopt similar NSW State of Biosecurity indicators.

Status and Trends

Why this topic matters

Invasive species are thought to impact over 70% of threatened plants, animals and insects. Weeds such as Lantana can drive out species and change ecosystems. Invasive animals such as feral cats can directly prey on threatened species, reducing numbers of plants and animals and changing the population dynamics of ecosystems. As well as significantly impacting native species and ecosystems, such invasions can also impact on agricultural productivity, social wellbeing and ecotourism (DPI 2018b).

Since 1788, around 3,000 introduced weeds have established populations in Australia. More than 1,750 of these have been recorded in NSW, with over 340 recognised as threats to native biodiversity (Downey et al 2010). Weeds now make up 21% of the total vegetation (DPI 2018b) and account for $1.8 billion a year in lost production.

Over the same period, more than 650 species of land-based animals have been introduced to Australia, of which 64 terrestrial and freshwater species have established wild populations in NSW (NLWRA & IACRC 2008). Although a smaller number of these are considered invasive, the annual economic loss to the NSW economy from the impact of pest animals in NSW is estimated to be more than $170 million including the cost of management actions.

Introduced fish species make up around 25% of freshwater fish species in the Murray-Darling Basin (Lintermans 2009).

It is not known how many insects and other invertebrates have been introduced into Australia in general and NSW specifically (Coutts-Smith et al. 2007).

Categories of invasive species

Invasive species are generally widespread, emerging or new, depending on their extent and ability to persist and spread:

- widespread species: invasive species that have been present for some time and have established a broad range across a region, habitat, or statewide

- emerging species: invasive species that have established a self-sustaining population and are expanding their range or can spread further

- new species: species that have not been recorded in NSW or established self-sustaining populations, but could invade and spread.

Examples of disease-causing pathogens are also included in this report.

Widespread invasive species

Widespread pest animals

Table 15.1 lists the top five widespread land-based pest animals that threaten native plants and animals (Coutts-Smith et al 2007). They are all listed in the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 as key threats to NSW threatened species. Because effective control of established invasive species is rarely feasible, these animals continue to maintain pressure on native species and ecosystems.

Table 15.1: Top five land–based pest animals threatening native animals and plants in NSW, ranked by the number of threatened species affected

| Common name | Scientific name |

|---|---|

| Feral cat | Felis catus |

| Red fox | Vulpes vulpes |

| Feral goat | Capra hircus |

| Rabbit | Oryctolagus cuniculus |

| Feral pig | Sus scrofa |

Other widespread pest species include animals introduced to NSW as domestic livestock with European settlement. Wild deer populations, for example, are still expanding in range. Wild deer occur along both sides of the Great Dividing Range in NSW. Three species (chital, red and fallow deer) also form significant populations west of the range. Wild deer distribution has increased from approximately 8% of the State in 2009 to 17% in 2016.

Widespread weeds

All parts of NSW are affected by weeds that threaten native animals, plants and ecosystems. Weed species, in terms of extent and diversity, are highest near the coast, particularly around major towns and cities, and in regions with high rainfall (Coutts-Smith and Downey 2006). The number of weeds recorded tend to decline from east to west (Coutts-Smith & Downey 2006). Weeds with the greatest impact on NSW native plants and animals on land have been recorded in Biodiversity Priorities for Widespread Weeds (DPI & OEH 2011).

Table 15.2 lists the top 20 widespread weeds on land in NSW, based on their level of impact on biodiversity (Downey et al 2010), and shows whether they are listed as a Weed of National Significance and/or as a key threatening process under the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Act.

Table 15.2: Top 20 widespread weeds posing a threat to native animals and plants in NSW

| Common name | Scientific name | Weed of national significance (WoNS) | Key threatening process (KTP) listing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Madeira vine | Anredera cordifolia | Yes | Yes |

| Lantana | Lantana camara | Yes | Yes |

| Bitou bush | Chrysanthemoides monilifera subsp. rotundata | Yes | Yes |

| Ground asparagus | Asparagus aethiopicus | Yes | Yes |

| Blackberry | Rubus fruticosus species aggregate | Yes | Yes* |

| Scotch broom | Cytisus scoparius subsp. scoparius | Yes | Yes |

| Japanese honeysuckle | Lonicera japonica | No | Yes* |

| Broad-leaf privet | Ligustrum lucidum | No | Yes* |

| Narrow leaf privet | Ligustrum sinense | No | Yes* |

| Cat's claw creeper | Dolichandra unguis-cati | Yes | Yes |

| Salvinia | Salvinia molesta | Yes | Yes* |

| Serrated tussock | Nassella trichotoma | Yes | Yes |

| Cape ivy | Delairea odorata | No | Yes |

| Blue morning glory | Ipomoea indica | No | Yes |

| Balloon vine | Cardiospermum grandiflorum | No | Yes |

| Lippia | Phyla canescens | No | Yes* |

| Bridal creeper | Asparagus asparagoides | Yes | Yes |

| Mickey Mouse plant | Ochna serrulata | No | Yes* |

| Turkey rhubarb | Acetosa sagittata | No | Yes* |

| Sweet vernal grass | Anthoxanthum odoratum | No | Yes |

Notes:

* Relates to 'garden escapes' key threatening process.

Widespread invasive aquatic animals

Invasive aquatic animals:

- alter the composition and function of aquatic ecosystems and habitat, and the diversity of native flora and fauna

- threaten native aquatic and land-based flora and fauna by preying on them or competing with them for food.

As a result, several key threatening processes have been listed under the Fisheries Management Act 1994 (FM Act) including: ‘Introduction of fish to waters within a river catchment outside their natural range’ and ‘Introduction of non-indigenous fish and marine vegetation to the coastal waters of New South Wales’.

Introduced freshwater fish compete with native fish and frogs for food and territory. They also prey on fish and frog eggs, tadpoles and juvenile fish.

Surveys of freshwater fish species over 2015–17 have found that few sampled sites are free from introduced fish. Most of the sites sampled have been within the Murray-Darling Basin, which generally comprises fewer native fish species than coastal and inland drainage divisions. In sample plots by DPI Fisheries, only 13% of sites were free of introduced fish and a small number of sites (4%) contained only introduced fish. Averaged across all sites, introduced taxa accounted for 36% of the fish species collected at each site, 37% of total fish abundance and 58% of total fish biomass, see figure 15.1 below.

There is no evidence of any new introduced fish species becoming established in the freshwater aquatic habitats of NSW during the reporting period.

Figure 15.1: Introduced fish recorded at DPI sampling sites

Notes:

Introduced trout in the sample sites includes brown trout and rainbow trout. Data sourced from over 800 sampling sites in the Murray-Darling Basin and northern coastal rivers.

European carp

Carp (Cyprinus carpio) have been in Australia for over 100 years and are now established in all states and territories, except the Northern Territory. Carp:

- can dominate freshwater fish communities in NSW, affecting water quality, native fish communities, fishing and irrigation

- are distributed across most of the Murray-Darling Basin and many coastal river systems, particularly in central NSW from the Hunter River in the north to the Shoalhaven River (including the Southern Highlands and Tablelands) in the south

- in some parts of the Murray-Darling Basin, comprise up to 90% of aquatic biomass, exceeding 350 kilograms of fish per hectare (DPI 2018b).

New invasive species, and emerging invasive species

New and emerging pest animals

Fire ants: On 28 November 2014, red imported fire ants were detected in Port Botany, possibly coming from Argentina. Although listed as a key threatening process, this was the first record of the ants in NSW.

The single nest at Port Botany was located and destroyed. Despite further surveillance, no further nests or ants have been located since the initial infestation and the population was declared eradicated in November 2016.

Yellow crazy ants: Invasion by crazy ants, Anoplolepis gracilipes, is a threat in NSW. Crazy ants are ranked as among the world's 100 worst invading pests. They can disrupt crops, and displace or kill invertebrates, reptiles, hatchling birds and small mammals. Crazy ants spray formic acid, which burns humans and animals.

Crazy ants have spread across parts of the Northern Territory. They have been intercepted in Australian ports regularly since 1988. Approximately 40% of interceptions have been in NSW. The Department of Primary Industries and local land services staff confirmed the presence of yellow crazy ants in Lismore in 2018 after a reported sighting by a member of the public. It is the first time in more than 10 years that the ant has been found in NSW since it was eradicated from Goodwood Island in Clarence River in 2008. The NSW Government has begun a surveillance and eradication operation and a national approach is being pursued under the National Invasive Ant Biosecurity Plan.

Cane toads: Cane toads were reported as an emerging species of concern in 2012 with viable populations established on the NSW far north coast. An isolated population of cane toads was found to be breeding in southern Sydney in 2010. This population has been part of a successful cane toad eradication program led by Sutherland Council, with no cane toads being found in this area since 2015.

New and emerging aquatic pests

Mozambique tilapia: Mozambique tilapia is an internationally recognised pest fish from southern Africa. It is a hardy fish that tolerates both fresh and salty water and was a popular ornamental species before being banned in NSW and other Australian jurisdictions. Tilapia has established populations that dominate native fish in parts of Queensland, including catchments that lie directly adjacent to the Murray–Darling Basin (MDB). In November 2014 a coastal population was detected in northern NSW, which it was found to be not feasible to eradicate. Research has suggested tilapia could become widespread if introduced into the MDB (MDBA 2011) but at the time of this report, the species has not been detected there. The NSW Government has established targeted local education and advisory programs so the community can identify the fish if it appears and notify their local council.

Red imported slider turtle: This turtle is considered an emerging species in some urban areas around Sydney. It originates from the midwestern states of the USA and north-eastern Mexico. However, non-native populations of wild-living red-eared slider turtles now occur worldwide due to the species being extensively traded as both a pet and a food item. The species is considered an environmental pest outside its natural range because it competes with native turtles for food, nesting areas and basking sites.

New and emerging weeds

Since 2013, six new species of weed known to be invasive in other regions of the world have established in the wild in NSW. Species that are of high risk and listed as State Prohibited Matter under the NSW Biosecurity Act 2015 include:

Mouse-ear hawkweed (Hieracium pilosella)

Mouse-ear hawkweed was first recorded in NSW in January 2015, in Kosciuszko National Park. The infestation was 150m2 with dense, heavily matted plants growing over native alpine vegetation. Surveillance around this infestation found another patch of >200m2. The areas were treated and, during 2017–18, only 109 plants were detected over 0.83m2, a more than 99% reduction in area infested by this weed. Surveillance and monitoring will continue for the next five years to ensure the seedbank is completely eradicated.

Orange hawkweed (Hieracium aurantiacum)

Originating from Europe, orange hawkweed is in the early stages of invasion in Australia in NSW, Tasmania and Victoria, but could invade over 27 million hectares of south-east Australia.

This weed was first located in Kosciuszko National Park after fires in 2003, near Jagungal Wilderness. The NSW Government controlled the weed, and in 2017–18, only 1,025m2 of orange hawkweed were found and promptly controlled.

Significant advances have been made in developing herbicide controls and new surveillance techniques. Since 2015:

- two weed eradication detector dogs have been trained to detect orange hawkweed through their sense of smell

- the distinctive orange flowers can be quickly detected by drones and algorithms aerially over much larger areas of remote terrain; in 2017–18, over 1,051 hectares were surveyed, compared to 415 hectares in 2016–17.

This increase in area surveyed resulted in the discovery of 35 new sites in 2017–18. All were small and in areas where seeds would not be easily dispersed by wind. The number of new sites detected has also decreased, and the NSW Government is certain this weed will soon be eradicated from the national park. Orange hawkweed had been detected at two sites near the national park in 2015 but these sites were effectively controlled.

In 2017, the NSW Government reviewed orange and mouse-eared hawkweed eradication programs and concluded that eradication of both species remains highly feasible. Full delimitation of these species is now the key and adequate level of resourcing must be maintained to ensure this result.

Pathogens

Pathogens are increasing threats to plant and animal biodiversity in NSW. Pathogens can seriously affect animal and plant production systems and human health.

Four pathogens are listed as key threatening processes under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016:

- beak and feather disease affecting parrot species

- dieback of native plants caused by the root-rot fungus, Phytophthora cinnamomi

- infection of frogs with chytrid fungus, resulting in the disease, chytridiomycosis

- myrtle rust fungi, affecting plants of the family Myrtaceae.

A strain of myrtle rust was first detected in Australia in April 2010 on the NSW Central Coast (Carnegie et al. 2010). From there, it spread rapidly, reaching bushland in south-east Queensland in January 2011. The full impact of myrtle rust is yet to be realised, but the latest research indicates that highly-susceptible species in NSW, such as Rhodamnia rubescens and Rhodomyrtus psidioides have already considerably declined in response to this pathogen (Carnegie et al. 2015). Other less widespread species in the family Myrtaceae have no natural resistance and a range that coincides with the predicted hotspots for myrtle rust (Kriticos et al. 2013; Berthon et al. 2018).

Pressures

Factors that worsen the effects of invasive species or increase their distribution

Habitat disturbance

Factors stressing the natural environment including the addition of nutrients, altered hydrological regimes, and the frequency and severity of altered fire regimes promote the invasion of introduced species. This, in turn, puts more pressure on native plants, animals and ecosystems (Lake & Leishman 2004).

Introducing weeds through trade

Greater mobility and the globalisation of international trade are significantly increasing the movement of people and goods across borders. This increases the risk of accidentally introducing pathogens, insects and other invertebrate pests.

Greater Sydney currently receives more than 38.5 million international visitors, over 500,000 tonnes of air freight and one million shipping containers every year (DPI 2018b).

Many new plant species have already been introduced to NSW via the nursery trade, with many escaping from gardens to become weeds (Groves & Hosking 1998). Of the weed species that threaten endangered species in NSW, 65% were introduced as ornamental plants (Coutts-Smith & Downey 2006).

Other industries that have introduced pests and weeds into NSW:

- the black-market pet trade introduces exotic animals, especially reptiles

- the aquarium industry introduces exotic fish such as goldfish and tilapia, and aquatic plant species that have been released into the wild and flourish

- the ballast water of cargo ships and hull biofouling help spread pests into the marine environment.

Expansions of range

Many invasive species have not yet reached the potential limits of their distribution. For example, weed species such as orange and mouse-ear hawkweed, boneseed, African olive, cabomba and some exotic vines occupy only a small part of their potential range.

Already widespread weeds such as lantana, bitou bush, blackberry and Coolatai grass can spread further without control.

Emerging pest animal species such as deer and cane toads have not yet reached their potential range. While deer are continuing to expand, the spread of cane toads has been contained.

Climate change

The impact of climate change on weed invasion is becoming clearer in Australia. As climate regimes continue to change, it is likely that new invasive plants will emerge (Duursma et al 2013).

The extent of suitable habitat for invasive species has been modelled and predicted under current and future climate change scenarios.

- The alpine ecoregion in NSW may be particularly vulnerable to future incursions by weeds (Duursma et al 2013).

- Changing climate regimes may create more favourable conditions for weeds in southern NSW.

- Many native species and ecological communities affected by climate change will become more vulnerable to the threat of pest animals and weeds (NSW Government, 2011).

As a result, climate change scenarios and species distribution models will be useful in predicting future breakouts and spread of invasive plants and to devise suitable management strategies.

Other issues affecting biosecurity

The New South Wales State of Biosecurity report 2017 (DPI 2018b) notes other pressures that are likely to affect biosecurity in NSW, including:

- the need to maintain the willingness of government, industry and the community to share responsibility for controlling invasive pests and weeds

- population growth combined with urbanisation and land clearing for development is providing an increasing biosecurity risk, but also opportunities to engage people in surveillance, detection and control

- the need to embrace new technology and strategies to tackle the changing risk profile of biosecurity in NSW.

Responses

Legislation and policy

The NSW Government determines priorities for control of, and resources to manage, invasive species. The highest priority species for protection are threatened species and other entities listed under the Biodiversity Conservation Act. For cross-tenure impacts, the community can participate through the regional planning process.

All land managers have a duty to prevent, eliminate or minimise the risk of invasive species under the Biosecurity Act 2015, including participating in coordinated regional strategies.

NSW Invasive Species Plan

The NSW Invasive Species Plan 2018–2021 (NSW Government 2018) focuses on the four goals to:

- exclude – prevent the establishment of new invasive species

- eradicate or contain – eliminate, or prevent the spread of new invasive species

- effectively manage – reduce the impacts of widespread invasive species

- capacity building – ensure the NSW Government and community can manage invasive species.

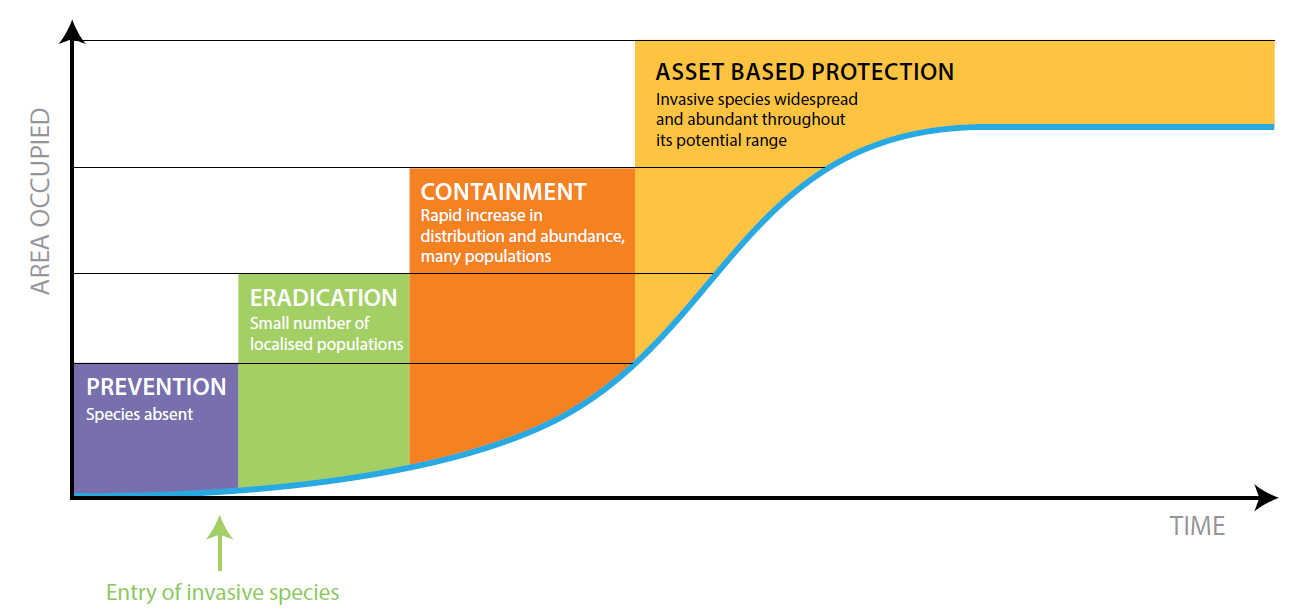

These four goals align with the invasion process from pre-arrival of new invasive species to widespread establishment (as illustrated in Figure 15.2). Prevention is the most cost-effective way to minimise the impacts of invasive species. Once an invasive species has appeared, it can colonise areas rapidly. Successful control requires a rapid effective response. Once widespread, the eradication of invasive species over wide areas of different land tenure is rarely practical. Priorities for the control of these species may include focused efforts in areas where the benefits of control will be greatest for environmental, primary production or community benefit.

The plan:

- dedicates resources to manage invasive species

- identifies key responsibilities of the key parties involved in invasive species management in NSW

- supplies critical actions to be undertaken up to 2021.

Figure 15.2: Actions appropriate to each stage of invasive species incursion

NSW Biosecurity Strategy 2013–2021 and NSW Biosecurity Act 2015

The NSW Government launched the NSW Biosecurity Strategy 2013–2021 in May 2013. The strategy:

- explains the principles for sharing responsibility for effective biosecurity management

- increases awareness of biosecurity issues in NSW

- outlines ways in which the NSW Government will partner with other government agencies, industry and the community to identify and manage biosecurity risks.

A key component of the strategy is the NSW Biosecurity Act 2015 and Biosecurity Regulation 2017. The Act and Regulation will provide for the prevention, elimination, minimisation and management of biosecurity risks.

One of the key components of this legislation is the introduction of a General Biosecurity Duty. This duty requires any person dealing with biosecurity matter (such as pest animals or weeds) or a carrier, and who knows or ought to know of the biosecurity risks posed by that matter, to take measures to prevent, minimise or eliminate the risk as far as is reasonably practicable. The occupier of lands (both private and public) is required to take all practical measures to minimise the risk of any negative impacts of pest animals or weeds on their land. The occupier could discharge their duty by complying with control actions outlined in the LLS regional strategic weed plans and regional pest animal management plans.

NSW Authorised Officers undertake regular audits and inspections to ensure implementation of biosecurity practices to enable ongoing market access for trade. In 2016–17, 6,650 compliance and enforcement activities were conducted to protect NSW biosecurity (DPI 2018b). Local Land Services and Local Control Authorities also support local land holders to meet their responsibilities.

Land Management (Native Vegetation) Code 2018

The Land Management (Native Vegetation) Code 2018 is created under section 60T of the Local Land Services Act 2013. The Code commenced on 25 August 2017 and facilitates native vegetation management on rural land, enabling landowners to productively manage their land while supporting biodiversity and managing environmental risks. The Code allows the removal of invasive native plant species on private land that have reached unnatural densities and dominate an area. Management of invasive native species promotes the regeneration and regrowth of native vegetation that is not invasive, contributing to positive environmental outcomes.

Programs

Containment lines

To effectively manage new and emerging invasive species, the best method is to eradicate or contain them before they can cause significant environmental impacts.

Establishing strategic containment lines can be an effective method of control. Containment lines are mapped lines, often delineated along a natural feature such as a river or along local government or other management boundaries.

A containment line is placed around the core distribution of the weed or pest, which is eradicated. Any population outside the containment line, and any isolated populations well away from the core distribution area are then fragmented or depleted and can be easily eradicated.

Regional weed and pest committees

The NSW Government has established regional weed committees and regional pest animal committees in each Local Land Services region. The committees coordinate regional pest animal and weed management activities on both public and private land. These committees have developed 11 Regional Weed Plans and 11 Regional Pest Animal Management Plans, which identify actions that can help land managers to manage weeds and pest animals on their land under the NSW Biosecurity Act 2015.

Saving our Species program

Biosecurity control measures provide a general level of protection for species and ecosystems. Saving our Species sets specific priorities for ensuring threatened species are secured in the wild. Many of the actions to recover species under Saving Our Species focus on controlling pest animals and weeds, which affect over 70% of listed threatened species, populations and ecological communities.

For more information on threatened species protection and Saving Our Species, see the Threatened Species topic.

National Carp Control Plan and NSW action

The National Carp Control Plan includes all Australian jurisdictions working in partnership to identify safe, effective and integrated measures to control carp populations in Australia, focusing on biocontrol methods.

NSW is a collaborative partner in research being undertaken as part of the National Carp Control Plan and participates in the Science Advisory Group, Policy Advisory Group, Operations Working Group, and Communications Working Group.

Future opportunities

Between 2008 and 2017, the NSW Government spent $107 million on significant biosecurity plant and animal disease and pest incident responses in NSW. It has also made a significant contribution to sharing costs to control incidents in other states and territories. Future opportunities include:

- Continual improvements to surveillance and biosecurity measures can help prevent new and potentially invasive species from threatening natural ecosystems and the productivity of farming systems.

- Development of biological control solutions and other new techniques will help provide opportunities to effectively and affordably manage widespread invasive species.

- Pathogens of native plants and animals continue to emerge as an increasing threat to natural systems and are likely to present challenges for effective management and control.

References

References for Invasive Species

Berthon K, Esperon-Rodriguez M, Beaumont LJ, Carnegie AJ & Leishman MR 2018, ‘Assessment and prioritisation of plant species at risk from myrtle rust (Austropuccinia psidii) under current and future climates in Australia', Biological Conservation, 218, pp. 154–62

Carnegie AJ, Lidbetter JR, Walker J, Horwood MA, Tesoriero L, Glen M & Priest MJ 2010, ‘Uredo rangelii, a taxon in the guava rust complex, newly recorded on Myrtaceae in Australia’, Australasian Plant Pathology, 39, pp. 463–6 [dx.doi.org/10.1071/AP10102]

Carnegie AJ, Kathuria A, Pegg GS, Entwistle P, Nagel M & Giblin FR 2015, ‘Impact of the invasive rust Puccinia psidii (myrtle rust) on native Myrtaceae in natural ecosystems in Australia’, Biological Invasions

Coutts-Smith A & Downey PO 2006, Impact of weeds on threatened biodiversity in New South Wales. Technical series No. 11, CRC for Australian Weed Management, Adelaide [www.southwestnrm.org.au/ihub/impact-weeds-threatened-biodiversity-new-south-wales]

Coutts-Smith AJ, Mahon PS, Letnic M & Downey PO 2007, The threat posed by pest animals to biodiversity in New South Wales, Invasive Animals Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra [www.pestsmart.org.au/the-threat-posed-by-pest-animals-to-biodiversity-in-new-south-wales]

Downey PO, Scanlon TJ & Hosking JR 2010, ‘Prioritising weed species based on their threat and ability to impact on biodiversity: A case study from New South Wales’, Plant Protection Quarterly, 25, pp. 111–26 [www.weedinfo.com.au/ppq_abs25/ppq_25-3-111.html]

DPI & OEH 2011, Biodiversity priorities for widespread weeds, prepared for the 13 Catchment Management Authorities (CMAs) by Department of Primary Industries and Office of Environment & Heritage, Orange (Authors: Whiffen LK, Williams MC, Izquierdo N, Downey PO, Turner PJ, Auld BA & Johnson SB) [https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/biosecurity/weeds/strategy/handbook/cmas]

DPI 2018a, Invasive Species Plan 2018–2021, Department of Primary Industries, Sydney [www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/biosecurity/weeds/strategy/strategies/nsw-invasive-species-plan-2018-2021]

DPI 2018b, New South Wales State of Biosecurity Report, Department of Primary Industries, Sydney [https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/biosecurity/managing-biosecurity/nsw-state-of-biosecurity-report]

Duursma DE, Gallagher RV, Rogers E, Hughes L, Downey PO & Leishman MR 2013, ‘Next-generation invaders? Hotspots for naturalised sleeper weeds in Australia under future climates’, PLoS ONE 8(12): e84222 [dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084222]

IUCN 2014, United Nations issues guidelines to minimize risk of invasive species, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Gland, Switzerland [www.iucn.org/news_homepage/news_by_date/?18462/United-Nations-issues-guidelines-to-minimize-risk-of-invasive-species]

Kriticos DJ, Morin L, Leriche A, Anderson RC & Caley P 2013, ‘Combining a Climatic Niche Model of an Invasive Fungus with Its Host Species Distributions to Identify Risks to Natural Assets: Puccinia psidii Sensu Lato in Australia’, PLoS ONE, 8:e64479

Lake JC & Leishman MR 2004, ‘Invasion success of exotic plants in natural ecosystems: The role of disturbance, plant attributes and freedom from herbivores’, Biological Conservation, 117, pp. 215–26

Lintermans M 2009, Fishes of the Murray-Darling Basin: An introductory guide, Murray-Darling Basin Authority, Canberra [www.mdba.gov.au/media-pubs/publications/fishes-murray-darling-basin-intro-guide]

MDBA 2011, Mozambique tilapia: The potential for Mozambique tilapia Oreochromis mossambicus to invade the Murray-Darling Basin and the likely impacts: A review of existing information, Murray-Darling Basin Authority, Authors: Michael Hutchison, Zafer Sarac and Andrew Norris – Department of Employment, Economic Development and Innovation [https://www.mdba.gov.au/sites/default/files/pubs/Tilapia-report.pdf (PDF 8.5MB)]

NLWRA & IACRC 2008, Assessing Invasive Animals in Australia, National Land and Water Resources Audit & Invasive Animals Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra [lwa.gov.au/products/pn20628]

OEH 2011, NSW Climate Impact Profile Technical Report: Potential impacts of climate change on biodiversity, Office of Environment & Heritage, Sydney [climatechange.environment.nsw.gov.au/~/media/43BD4541486144EF8858666D20D1E85B.ashx]