Overview

A contaminated site is a place where the soil or groundwater has been polluted by harmful substances. The level of contaminants usually exceeds what is considered safe for people and the environment.

Harmful substances may include:

- heavy metals, such as lead, arsenic and copper

- chemical substances, such as solvents and oils

- agricultural chemicals, such as insecticides and herbicides

- ground gases or vapours

- asbestos

- radioactive materials.

There are many contaminated sites in NSW. These include large, complex sites often grouped together, typically having been used for heavy industrial purposes, such as gasworks, smelters or petroleum infrastructure (refineries and terminals).

Smaller contaminated sites can also be found in urban and rural areas previously used for agriculture or commercial purposes. These include service stations, fuel storage depots, dry cleaning premises and chemical storage areas.

Before European colonisation, the lands, waters and skies of what is now NSW were free of modern or human-made contaminants. Country was cared for by Aboriginal people through practices that nurtured and preserved the environment for thousands of years.

Since colonisation, contamination has resulted from industrial pollution, poor waste disposal and the use of persistent and toxic chemicals in domestic, agricultural and industrial settings.

Contaminants can remain in the environment for a long time, even after the cause of the contamination has ceased.

Contaminants can also move in the environment. For example, contaminants in soil can get into groundwater and flow on to affect neighbouring land and surface waters.

See the , and topics for more information about water pollution.

How does contaminated land affect us?

Some contaminants in soil and in soil and water can move through the environment to plants, animals and humans.

They can travel a long distance from their original source site through the ground and enter nearby surface waterbodies.

Exposure to some types of contamination may cause immediate harm to human health. For example, some gases emitted by contaminated land create an explosion risk.

Other exposures to contaminated land that could cause harm include:

- direct skin contact, drinking the water or watering a garden with contaminated groundwater

- inhalation of vapours emissions that have entered nearby buildings

- skin exposure to contaminated soils or inhalation of vapours by construction workers during excavation or sub-surface works.

These harmful contaminants travel under the ground, meaning there is often no visible or obvious signs of contamination on the surface.

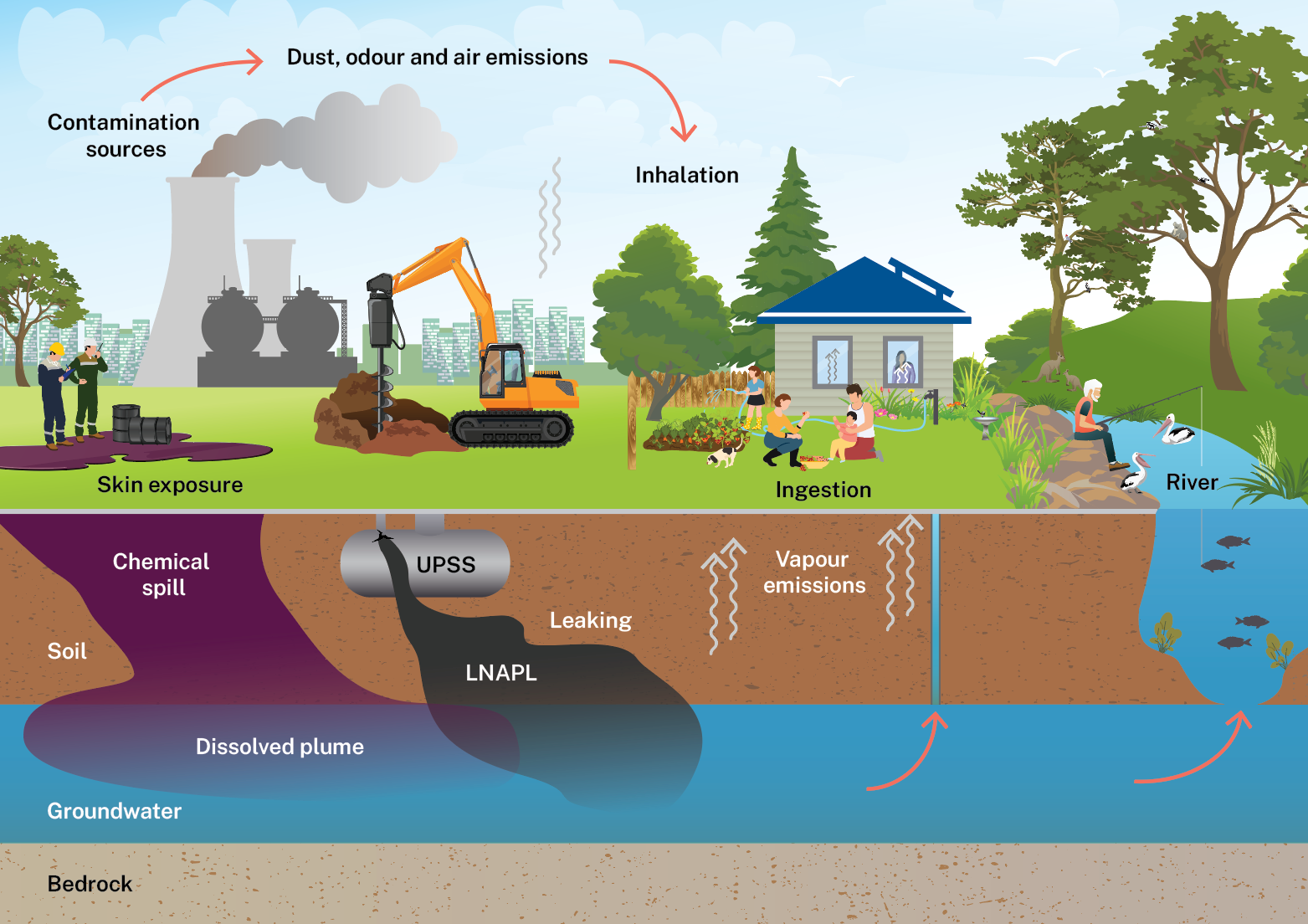

Image P5.1 demonstrates how contamination may occur and the impacts it might have on the environment and human health.

- The source of contamination, such as a chemical spill or underground petroleum storage system (UPSS) leaks a chemical substance or a light non-aqueous-phase liquid (LNAPL) into the soil.

- This causes a dissolved plume, or pathway into the soil or groundwater.

- The contaminant can then impact the environment, including harming animals, plants and waterway ecosystems. It can also affect humans if they are in contact with it. This contact could be through inhalation, ingestion or skin exposure during activities such as digging, swimming or drinking untreated bore water.

Image P5.1: Conceptual diagram of contaminated lands processes and impacts

Notes:

Underground petroleum storage system (UPSS): used to store and dispense petroleum products, typically at petrol stations. These systems consist of underground tanks and pipes, which degrade as they age, potentially resulting in contamination.

Light non-aqueous-phase liquids (LNAPL): liquids such as oil or petroleum that are less dense than water and do not mix well with it. When spilled, they can float on the surface of groundwater, potentially contaminating soil and water.

A dissolved plume: refers to a spread of contaminants that have dissolved into groundwater or another liquid and are now moving away from the original contamination source. Plumes can be hard to detect and manage, spread over large areas, and can affect drinking water supplies and ecosystems.

While contaminants include a broad range of substances, some are more prominent in environmental and public health discussions, usually due to their widespread historical use, persistence in the environment or potential to harm human health.

Contamination is a significant issue for Aboriginal communities throughout NSW, posing serious health risks to Aboriginal peoples’ wellbeing and encompassing emotional cultural, physical and spiritual health.

In addition to the health risks, contamination issues are significantly impacting the health of Country and the ability of Aboriginal peoples to live on Country maintaining a connection with land, waters and sky for cultural and economic purposes.

Contamination in NSW

A number of contaminants of concern in NSW have been subject to dedicated programs to remove them from the environment and prevent further contamination.

Petroleum

Underground petroleum storage systems (UPSS) are a common source of land and groundwater contamination in NSW. They exist in many places where fuel is used, with examples including petrol stations, marinas, work depots and airports. As they may leak, those who operate the UPSS must prevent, report and fix leaks where they occur.

Asbestos

Asbestos was a common building material and decorator product in homes from the mid-1940s to the mid-1980s, when it was discontinued (). It can still be found in one in three Australian homes and in commercial and non-residential structures ().

Most asbestos contamination results from poor site management practices during construction or demolition. Inhalation of asbestos fibres can lead to serious diseases over time, such as lung cancer and mesothelioma.

PFAS

PFAS (per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances) are durable chemicals known for accumulating and staying in the environment for a long time (). It is a group of substances that include perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHxS).

Due to their fire retardant, waterproofing and stain resistant qualities, these chemicals were widely used in industrial products and some types of fire-fighting foams worldwide. PFAS can also be found in low concentrations in many consumer products like food packaging, non-stick cookware, fabric, furniture and carpet stain protection applications, clothing and shampoo.

As a result, people are exposed to small amounts of PFAS in everyday life. Products containing PFAS are being phased out around the world. Research into the effects of PFAS on organisms, such as potential multigenerational effects on aquatic wildlife, is ongoing. Work is also underway to understand and predict the behaviour of different PFAS in the environment.

Lead

Lead does not break down in the environment and past contamination can still affect us today.

Sources of lead contamination include paint from before the 1970s, the fallout from vehicle exhaust fumes before leaded petrol was banned in 2002, waste from mines and industrial sources in soil.

For example, lead has been mined in Broken Hill for many years and is present in the dust and soil, resulting in elevated blood lead levels in the community, particularly in children.

It is a naturally occurring metal and is still in use in a range of household, recreational and industrial products.

Exposure to lead is linked to harmful effects on organs and bodily functions. Elevated blood lead levels can cause anaemia, kidney disease and neurological or developmental harms.

Other contaminants of concern

There are many substances that are known to have caused contamination in NSW. These can all have various impacts on the environment, including animals and plants, soil, waterways and human health.

These include, but are not limited to:

- heavy metals, such as zinc (from galvanised iron and tyres) and chromium (from tanneries)

- polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, from coal tar

- perchloroethylene, from dry cleaning chemicals

- agricultural pesticides, from past and current agricultural practices.

See the EPA website for more information about contaminants.

Regulation of contaminated sites

In NSW, contaminated sites are regulated under the Contaminated Land Management Act 1997. This regulation is carried out by various government agencies depending on the level of contamination.

‘Significantly contaminated’ sites are regulated by the NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) to ensure that the land is managed or remediated appropriately by the person responsible for the contamination. The responsible person could be the polluter, the landowner or another appropriate person.

To determine whether land is ‘significantly contaminated’, the EPA assesses:

- any harm caused or which could be caused by the contamination

- the toxicity, persistence, bioaccumulation and concentrations of the contaminants

- how humans or the environment could be exposed to the contamination

- whether the contamination has migrated or could migrate to other land.

Polluters or landowners must report contamination to the EPA where:

- the concentrations of contaminants exceed a set limit

- whether people have been, or could be, exposed to those contaminants

- whether the contamination has migrated, or could migrate, to neighbouring land.

Contaminated land that is not determined to be ‘significantly contaminated’ is managed by planning authorities, including local councils, through the land use planning and development process.

Planning authorities must consider whether the contamination will affect the suitability of a site if the land use changes.

In some instances, particularly when the land use has involved hazardous substances, the legacy may threaten humans or the environment, or it may affect the current or future use of the land. Not all contamination precludes future productive land uses ().

Contaminated land is managed through a combination of legislation and policies at a state and federal level (see Table P5.1).

Table P5.1: Current key legislation and policies relevant to contaminated sites in NSW

| Legislation or policy | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Contaminated Land Management Act 1997 | Regulates the identification, management and remediation of significantly contaminated land in NSW. |

| Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 | Outlines provisions for creating environmental planning instruments, processing development applications, and issuing planning certificates for land. It also sets out the need for planning authorities to consider the Managing Land Contamination – Planning Guidelines. These guidelines provide advice to planning authorities on how contamination must be considered in rezoning and development applications. |

| Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997 | Provides legislation for the EPA and other public authorities to prevent, control and investigate pollution in NSW. |

| National Environment Protection (Assessment of Site Contamination) Measure 1999 (revised 2013) | Sets out the national risk assessment framework for the assessment of contaminated sites in NSW. It includes schedules which cover a range of subjects including human health and ecological investigation criteria, site characterisation, laboratory analysis, health risk assessment, ecological risk assessment and community engagement. |

| Guidelines for Fresh and Marine Water Quality, (Australian and New Zealand) 2018 | Provides key guidelines for the assessment of environmental water quality in NSW, applicable to both marine and fresh waters. |

| State Environmental Planning Policy (Resilience and Hazards) 2021 | Provides a statewide planning approach for the remediation of contaminated land where development is proposed. A planning authority must not consent to any development on land unless it has considered whether the land is contaminated, and if so, whether the land is suitable (or will be suitable, after remediation) for the purpose for which the development is proposed. |

| PFAS National Environmental Management Plan 2.0 (HEPA) 2020 | Sets guidance and approaches to the management of PFAS contamination in Australia. It includes detailed sections on PFAS-contaminated site assessment, management, transport and remediation. |

Notes:

The EPA website has a list of statutory guidelines and non-statutory guidelines for dealing with different types of contamination and additional guidance documents.

See the Responses section for more information about how are managed in NSW.

Related topics: | | | | |

Status and trends

Contaminated sites indicators

Two indicators are used to assess the state of contaminated sites in NSW:

- Number of regulated contaminated sites are those determined to be ‘significantly contaminated’ and requiring oversight by the EPA (see Number of contaminated sites).

- Number of sites where the regulation has ended are those assessed as being no longer significant enough to warrant regulation by the EPA (see Remediation of contaminated sites and Regulation and assessment of sites).

Both the number of regulated contaminated sites in NSW that required regulatory oversight by the EPA and the number of sites assessed as being no longer significant enough to warrant regulatory oversight remained moderate and stable in the 2023–23 period (see Table P5.2).

Table P5.2: Contaminated sites indicators

| Indicator | Environmental status | Environmental trend | Information reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of regulated contaminated sites | Stable | Good | |

| Number of sites where the regulation has ended* | Stable | Good |

Notes:

*The EPA ends regulation on a site when there is evidence that the land contamination is no longer significant, for example because the site has been remediated or the contamination is appropriately managed so that it does not pose a risk to human or environmental health.

Indicator table scales:

- Environmental status: Good, moderate, poor, unknown

- Environmental trend: Getting better, stable, getting worse

- Information reliability: Good, reasonable, limited.

See to learn how terms and symbols are defined.

Number of contaminated sites

The net number of EPA-regulated contaminated sites remained stable at an average of 202 sites per year between 2021–23 (see Figure P5.1).

Figure P5.1: Net number of EPA-regulated contaminated sites in the period, 2005–23

Notes:

Regulation is managed by the EPA under the Contaminated Land Management Act 1997.

Calculated as cumulative total sites regulated minus cumulative total sites remediated.

Remediation of contaminated sites

The number of EPA-regulated contaminated sites where regulation has ended continues to fluctuate but remain mostly stable between 2021–23 (see Figure P5.2).

EPA regulation ends once a contaminated site has been remediated or the risks from contamination are being appropriately managed.

Figure P5.2: Contaminated sites where regulation was ended, 2005–23

Notes:

Regulation is managed by the EPA under the Contaminated Land Management Act 1997.

Regulation and assessment of sites

Between 2005 and the end of 2023, the EPA declared 408 sites to be significantly contaminated under the Contaminated Land Management Act 1997. The EPA has ended the regulation on 203 sites, for example, this may be because a site had been remediated or the contamination had been managed.

Figure P5.3 shows that both numbers of regulated sites and the number of sites where regulation has ended rose steadily between 2005 and the end of 2023.

- Between 2021–23, 133 new sites were reported. Of these, 25 were declared as significantly contaminated land by the EPA.

- In this same period, EPA regulation was ended at 18 sites.

Figure P5.3 Cumulative total of sites regulated and number of sites where regulation was ended, 2005–23

Notes:

Regulation is managed by the EPA under the Contaminated Land Management Act 1997.

Regulated sites by contamination type

Land declared to be significantly contaminated between January 2021 and December 2023 was associated with:

- service stations (24%)

- landfills (8%)

- the metal industry (8%)

- gasworks (4%)

- the chemical industry (4%)

- other petroleum industries (such as fuel depots and terminals) (4%)

- other industry (includes transport depots, timber yards, mines, power stations) (40%)

- unclassified (such as contaminated fill, railway uses and commercial activities) (8%).

Since 2021, service stations and other petroleum industries have accounted for 28% of newly regulated sites, primarily in relation to underground petroleum storage systems.

Figure P5.4 shows fluctuations in the number and type of new sites regulated every year from 2005 to 2023. While service stations are the largest category throughout, the number of ‘other industry’ regulated sites increased in 2022.

Figure P5.4: Newly regulated sites by contamination type, 2005–23

Notes:

Regulation is managed by the EPA under the Contaminated Land Management Act 1997.

Since 2005, service stations have been the largest category of contamination type at 79% (see Figure P5.5).

Figure P5.5: Cumulative total of newly regulated sites by contamination type, 2005–23

Notes:

Regulation is managed by the EPA under the Contaminated Land Management Act 1997.

Contamination affecting Aboriginal communities

Of particular concern is legacy contamination on lands returned to Aboriginal communities under the NSW Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983 or the Commonwealth Native Title Act 1993.

The level and type of contamination on discrete Aboriginal community lands have not been properly documented and legacy contamination continues to be a major issue and concern.

A discrete Aboriginal community is typically a former Aboriginal reserve or mission where Aboriginal people were forced to live during the 1900s.

These homes, and the land they are on, were transferred from the NSW Government to Local Aboriginal Land Councils under the NSW Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983. There are 61 of these communities across NSW where Aboriginal peoples still live today.

These communities experience high levels of legacy contamination, as they were often built on or next to landfills, mines and heavy industry. When the land was returned to Local Aboriginal Land Councils, it was generally handed back as is, including any legacy contamination.

A first-hand account highlights the impact of legacy contamination on current living conditions (see the topic's section for the full story):

‘In my community’s history, we were forced to live on the actual living rubbish tip.

I’m only 43 years of age. I grew up with the rubbish being dumped in our backyards as kids, we didn’t know any better and we played in that. There’s medical waste. There’s asbestos. There’s development waste, industrial waste. Everything you could think of was just dumped in our places. None of that has been dealt with.’

Steven Ahoy, member EPA Aboriginal Peoples Knowledge Group 2024

A response to this can be found in Truth Listening within the Responses section of this topic.

Contamination issues due to illegal dumping, inadequate waste management services and the high prevalence of asbestos in houses also affect these communities.

Poor government housing practices in some Aboriginal communities resulted in the demolition of asbestos-containing buildings and the abandonment of waste materials on site.

Affordable housing options for Aboriginal communities are often located in high-risk areas. As a result, Aboriginal people are disproportionately affected by airborne industrial contamination. The lack of ongoing maintenance to the properties also exposes residents to contaminated air, water and soil.

This is the case in Broken Hill, where exposure to mining dust and flaking lead-based paint in homes has resulted in high rates of lead poisoning in residents ().

Infants and children living in these homes are exposed to lead and are at risk of impaired brain and nervous system development. This can result in global developmental delay, behavioural and learning difficulties and intellectual disabilities.

Programs to reduce lead exposure by capping dust sources, educating communities and improving housing have significantly reduced lead levels since the early 1990s ().

Despite these programs, blood lead levels in children in Broken Hill are still among the highest in the developed world (). The risk of lead poisoning increases significantly for Aboriginal children.

In 2023, levels exceeded 5 micrograms per decilitre (the national limit) in 74% of Aboriginal children and 37% of non-Aboriginal children in Broken Hill aged one to four years ().

Pressures and impacts

Population

As the population of NSW increases, our reliance on potentially polluting industries, such as mining, intensive agriculture and electricity generation, may increase. A potential by-product of these industries is the increase in harmful chemicals and pollutants entering the soil, water and air.

Hazardous chemical substances can cause serious to the environment and human health. Although exposure from many of these chemicals have dropped, exposure to some substances with unknown effects still remains.

As the State’s population grows, the demand for housing increases, prompting redevelopment of contaminated, former industrial or agricultural land for residential use, particularly in major coastal cities, such as Sydney.

Planning authorities must consider whether contamination will compromise the suitability of a site for a proposed land use ().

See the topic for more information.

Impact on Aboriginal communities

Exposure to contamination through dust, waters, air or food causes serious harms to human health. In addition, contamination of Aboriginal lands, places, communities and culture significantly impacts connection with Country.

Contamination limits the options for Aboriginal peoples to continue cultural practices, such as hunting and gathering of food or medicine and sharing these traditions with their community. Contamination both removes access to Country and eliminates the option of a place of belonging or knowing, therefore eroding safe and healthy communities.

The presence of contamination can also impede or delay other government initiatives and investments aimed at assisting Aboriginal communities. For example, the Roads to Home program provides significant infrastructure, such as roads and lighting and opportunities to subdivide land. Asbestos is a significant barrier to this program, preventing government investment from achieving its purpose and blocking economic advantage for Aboriginal communities ().

Remediation

Remediation of contaminated land is expensive, complex and involves a number of different stakeholders.

In NSW, the ‘polluter pays’ model requires the polluters to clean it up. Some polluters may lack the funds or may no longer exist as companies, which potentially passes the burden on to the owner of the land, or in rare cases the State or Local Government.

The demand and financial incentives for remediating contaminated land are not as available in more regional or rural areas, which can increase the challenges of cleaning-up sites in these communities.

The nature and extent of land contamination is often difficult to fully understand and manage. Given the large range of potential contaminants, many of which behave in different ways, there is no single way of investigating or cleaning up a contaminated site. Every site needs to be considered individually, considering the contamination and the site conditions.

Assessing the risk from contaminants relies on obtaining a lot of information about them, the site characteristics and how the contamination may affect human health and the environment. This complex work needs to be done by highly-qualified specialists.

Many different stakeholders can be involved in the management of contaminated land, including the site owners, neighbours, the community and regulators. This means contaminated land management must consider the views of many different people.

Waste disposal

Regulating unlawful disposal of waste is difficult and costly.

Over the last reporting period, unauthorised waste management and disposal practices have caused several problems to emerge. These can result in land pollution or contamination, increasing pressure on regulatory systems.

The use of materials that are non-compliant with the NSW Resource Recovery Framework (such as asbestos) in construction and other industries can also pollute or contaminate land.

See the topic for more information.

Climate change

Climate change, driven primarily by human activities, such as burning fossil fuels, deforestation and industrial processes, is significantly altering Earth’s climate patterns.

Scientists and regulators consider the impacts of climate change in their assessment and management of contaminated sites and the measures needed to adapt ().

Extreme climate and weather, such as extreme rainfall, can have many effects on contaminants ().

Extreme rainfall can transport pollutants and contaminants, such as sewage, chemicals and microplastics, into waterways, posing risks to wildlife and human health ().

These contaminants, which may have settled in soil and groundwater, can be disturbed and spread over larger areas during flooding, potentially contaminating new sites, including sources of drinking water and agricultural land.

Responses

Managing contaminated sites

In April 2024, the NSW Government amended eight Acts and three regulations under the Environment Protection Legislation Amendment (Stronger Regulation and Penalties) Act 2024.

This strengthened regulatory requirements and penalties across environment protection legislation to present a strict deterrent for non-compliance. It enabled the EPA to issue preliminary investigation notices to determine whether substances pose potential risks to human health exist or have existed in a location.

This included an increase in the jurisdictional limit of local courts and maximum penalties for certain offences and simplified the process for setting policies. The amendments are summarised on the EPA website.

In October 2023, the NSW Government amended the Waste Recycling and Processing Corporation (Authorised Transaction) Act 2010. Government agencies now have the option to transfer government-owned contaminated land managed by them to the Waste Assets Management Group or engage it to coordinate rehabilitation.

EPA Strategic Plan 2024–29

In its Strategic Plan for 2024–29, the EPA is focusing on stronger protection of the environment and community:

- from high-risk legacy contamination and emerging chemicals

- through providing planning development advice and regulating pollution from industry.

Addressing contamination issues on Aboriginal lands

NSW Crown Lands is aware of legacy contamination on Aboriginal lands returned to traditional owners under the NSW Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1983. A procedure established in 2016 is used to assess risks and consult with recipients. Crown Lands is developing policies and procedures to reduce the risk of contamination, in addition to pests, weeds and poorly maintained infrastructure, on lands returned to Aboriginal communities.

The EPA works closely with the NSW Asbestos Coordination Committee to safely manage asbestos in discrete Aboriginal communities and Aboriginal-owned housing, and to increase Aboriginal peoples’ understanding of the risks, how to stay safe and whom to ask for help.

The EPA has been working with NSW Public Works since 2019 to remediate legacy asbestos contamination in communities identified in a 2017 Ombudsman’s report. During remediation, the EPA has offered free training in asbestos removal and temporary employment to help upskill and educate the community on asbestos.

Asbestos and other contaminants in housing remain significant issues in other Aboriginal communities.

The NSW Government is providing support to reduce lead exposure in Broken Hill by offering free blood lead screening, providing community education, reducing dust sources and improving housing.

The impact of contamination on the health of Country and the obligations of Aboriginal people to care for it was recognised in a 2023 compensation settlement between the Commonwealth and the Wreck Bay Aboriginal community in relation to PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) on their lands and in their waters ().

Truth Listening

, within , is a personal story from Steven Ahoy, Anaiwan man and a member of the EPA’s (APKG).

Truth Telling is a way to acknowledge the ongoing impact of past injustices through the contemporary experiences of Aboriginal peoples ().

Truth Listening is implicit to this process. It requires us to accept discomfort and be open to complexity and uncertainty. It helps ensure truths are heard, which is essential for those who have suffered to feel recognised or respected.

The EPA is committed to Truth Listening. The goal of Truth Listening in the State of the Environment 2024 is to help drive positive change for Aboriginal peoples and for the environment.

Consistent with the its Statement of Commitment to Aboriginal peoples, the EPA is committed to actively learn from, and listen to, Aboriginal voices, cultures and knowledge. Part of this learning and listening includes welcoming Truth Telling and engaging in the practice of Truth Listening.

For information about the EPA’s investigation into the environmental issues raised in this Truth Telling story, visit the EPA website.

Voice of Country

The welcoming of Truth Listening in the State of the Environment 2024 also aligns with the invitation offered in the Voice of Country being to ngarragi – ‘to listen, learn and remember’. See the theme for more information.

NSW site auditor scheme

In 2022, the EPA accredited six new auditors for the NSW site auditor scheme, bringing the total to 51 across NSW.

Auditors in this scheme review investigation, remediation and validation work done by contaminated land consultants, increasing the certainty that contamination assessments and remediation have been completed to the right standard.

The scheme is important in assisting planning authorities in their decision-making. For example, where land is being redeveloped for a more sensitive land use, such as housing, auditors can help consent authorities feel confident the land is suitable for that use.

The scheme is administered by the EPA under Part 4 of the Contaminated Land Management Act 1997.

Investigation of PFAS (per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances)

In 2022, a new law was introduced through the Protection of the Environment Operations (General) Regulation 2022.

This law bans and restricts the use of PFAS firefighting foam in NSW, reducing its impact on the environment while still allowing its use for preventing or fighting catastrophic fires by authorised agencies ().

See the NSW Government PFAS Investigation Program website for more information.

The EnHealth guidance statement on PFAS provides updated PFAS health guidance in light of recently completed research into the human health effects of PFAS and exposure in Australia.

In 2024, the Australian Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water released the draft PFAS National Environmental Management Plan (NEMP) version 3.0.

This draft contains new guidance and standards for investigating, assessing and managing PFAS waste and contamination. It will be released in early 2025.

See the Australian Government PFAS Taskforce website for more information about the whole-of-government coordination and oversight of Australian Government responses to PFAS contamination.

The National Health and Medical Research Council is currently working with the Australian Government Department of Health, Food Standards Australia New Zealand, EnHealth and NSW Health to review the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines.

Under the NSW Public Health Act 2010, NSW Health is the regulator of drinking water and monitors water suppliers’ compliance with the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines. The guidelines, developed by the National Health Medical Research Council include health-based guideline values for PFAS in drinking water and are currently being reviewed.

WaterNSW is responsible for many of the State’s drinking water dams. While drinking water guidelines do not apply to raw, untreated water, WaterNSW can undertake investigations where PFAS are found in the drinking water catchments of the dams.

Water utilities, such as Sydney Water and Hunter Water, are responsible for the drinking water from the tap. If a risk from PFAS is identified to treated drinking water, the water utility will monitor and manage any risks.

Managing asbestos contamination

Legacy fill sites

Since 2017, under the James Hardie Program, the EPA has reviewed and assessed 50 sites in NSW where asbestos waste was historically used to fill land. These sites, mainly in Western Sydney, have residential, business, industrial or open space uses. Of the 50 sites, 29 had already been significantly remediated, redeveloped or capped. It is possible that additional sites remain to be found.

At various sites, asbestos management plans have been implemented to protect residents, workers and the public. These plans provide guidance on maintaining grass cover, minimising dust generation and managing asbestos-containing materials safely.

NSW Asbestos Coordination Committee

The committee was formed in 2020. Its longer-term agenda is set out in Asbestos in NSW: Next Horizon. It identifies priorities over the next five years that will be driven by Australian, State and Local Governments on the committee, as well as Aboriginal land councils.

The committee focuses on three immediate priority areas:

- keeping people safe through awareness and training

- dealing with legacy asbestos in discrete Aboriginal communities

- improving asbestos waste disposal and disaster waste management.

Asbestos in Aboriginal community-owned housing will continue to be a focus for the medium-term.

Managing lead contamination

The NSW Government is undertaking a range of actions and programs to support the management of historical lead contamination.

Broken Hill Environmental Lead Program

The NSW Government continues to work on addressing community concerns surrounding lead and high blood lead levels, especially in children.

This educational, environmental and health campaign is designed to help the population of Broken Hill to manage exposure to lead and to support the identification and prevention of potential lead-related health risks.

It aims to undertake annual blood lead level screening of all resident children aged under five years. A blood lead level equal to or above 5 micrograms per decilitre (μg/dL) is a notifiable condition in NSW.

Its LeadSmart community awareness and education program is designed to manage the risks of lead in pregnancy, hygiene, diet and lifestyle. LeadSmart saw a 10% increase in participation rates in blood lead testing of children from 2015 to 2019 ().

More information can be found under the Contamination affecting Aboriginal communities section.

Captains Flat Soil Sampling Program

In February 2020, elevated levels of lead were discovered near the legacy Lake George Mine at Captains Flat, a small former mining town south-east of Queanbeyan ().

In November 2023, the NSW Government began remediation work on the site. The EPA collected samples on public and private land, provided advice on remediation strategies, and helped in developing a lead management plan for the area. Soil samples from 80 locations on public land and 65 homes have so far been tested.

In 2022, the program published a Lead Management Plan for Captains Flat. The remediation project will involve management of the mine and eventually will see the revegetation of the site by mid-2026 ().

See the Captains Flat Contamination webpage for more information.

Lead management in North Lake Macquarie

In 2013, investigations found lead oxide fallout from the Pasminco smelter on North Lake Macquarie had affected surface soils in Boolaroo, Argenton and Speers Point. Black slag was also found, containing high levels of leachable heavy metals, being used as fill material ().

The Lead Abatement Strategy was developed to minimise exposure to contaminated soil on residential properties. Soil lead levels were tested and abatement works were conducted to ensure an effective physical barrier between residents and contaminated soil.

Work continues with the strategy, and is a collaboration between EPA and Lake Macquarie City Council and other agencies.

See the Lead soil disposal for Lake Macquarie residents website for more information.

Recent government remediation

The projects below provide examples of sites that have been or are in the process of being remediated or managed by the NSW Government.

Underground petroleum storage systems in groundwater-dependent communities

Since 2022, from a dataset containing 7,559 potential underground petroleum storage system sites in NSW, the EPA has identified 16 sites in groundwater-dependent communities as priorities for further investigation.

The EPA has investigated these sites (in collaboration with the local council), with site inspections and sampling (where possible) at 10 sites.

Groundwater contamination was found at two sites, which are being managed by the local council with assistance from the EPA.

Old Radium Hill Refinery, Hunters Hill – site remediation

The contamination stems from a radium processing plant and a carbolic acid plant that operated in the late 1800s through to the early 1900s. Elevated concentrations of coal tar waste material and heavy metals were present at the site.

The site was approved for remediation in 2021. The Hunters hill site remediation was completed 2024, allowing the site to be used for housing.

Waratah Gasworks, Newcastle – site remediation

Substances associated with former gasworks sites typically include tars, oils, hydrocarbon sludges, spent oxides (including complex cyanides), ash and ammoniacal recovery wastes.

In 2021, the EPA declared the site at the former Waratah Gasworks (1889–1926) as significantly contaminated and ordered a clean-up of the site.

Under the Property and Development NSW (PDNSW) and Waste Assets Management Corporation (WAMC)’s action plan, remediation work to demolish, excavate and remove tar pits and a gasholder began in September 2023 and is expected to finish by September 2025.

Truegain, Rutherford – site remediation

After the EPA suspended Truegain’s environment protection licence in 2016 and the company entered liquidation, PDNSW and WAMC took over responsibility for remediating the contaminated Truegain waste oil processing site in Rutherford.

They have focused on soil and groundwater clean-up, including removing above-ground liquid infrastructure and treating 11,000 tonnes of industrial wastewater and 135 steel tanks.

They are now planning for soil remediation to prevent contaminants from spreading ().

Pasminco, Cockle Creek, Boolaroo – land management

Pasminco Cockle Creek Smelter Pty Ltd operated a lead and zinc smelter in Boolaroo for more than a hundred years, causing significant soil contamination.

Following the smelter’s closure in 2003, the NSW Government assumed ownership and management of the site to ensure community and environmental safety.

The Lake Macquarie Smelter Site (Perpetual Care of Land) Act 2019 facilitated the transfer of the site to the Hunter Central Coast Development Corporation, with PDNSW now responsible for managing containment cells to protect residents and the environment.

Bare Creek Bike Park, Belrose – site remediation and management

The WAMC has remediated a former landfill in Belrose, Sydney, transforming it into public open space with a new bike park.

This project shows how government-owned land can be repurposed for community benefit. Working closely with the local council and residents, WAMC designed, built and manages the site.

The waste mass continues to generate gas and contaminated liquid, which are safely managed by WAMC.

Ampol Newcastle terminal – regulation of significant contamination

The former fuel terminal in Wickham operated for more than 70 years. The site is surrounded by light industry and commercial properties, with homes nearby.

In 2016 and 2019, the EPA declared the terminal and a portion of the adjacent land as significantly contaminated under the Contaminated Land Management Act 1997. Contamination is known to have spread beneath other properties.

The first stage of the clean-up is nearing completion.

Investigations are progressing to determine whether more clean-up work is needed, with a site plan including assessment, monitoring, remediation and keeping the community informed.

Future opportunities

Improving asbestos management

There is a need for more consistent standards in the management of asbestos contamination.

One area, for example, is the overlap between the contaminated land and waste regulatory frameworks. This inconsistency can complicate on-site reuse of asbestos-contaminated soil ().

The Office of the NSW Chief Scientist and Engineer is doing an independent review and advising on the management of asbestos contaminants in waste and recovered materials in NSW.

This work is a continuation on improving the EPA’s Resource Recovery Framework. The framework facilitates the recovery of resources in NSW, by keeping materials circulating in the economy.

The advice, expected in late 2024, will inform how the existing approach could be refined and improved.

It is an important step in ensuring better asbestos management outcomes for both human health and the environment.

Treatment and disposal of harmful substances

There is an ongoing challenge in the treatment and disposal of legacy contaminants. There are varying treatment standards for contaminants across jurisdictions.

HEPA (the Heads of EPA Australia and New Zealand) is an informal alliance of environmental regulation leaders from Australia and New Zealand. The EPA represents NSW in this alliance.

This collaboration seeks to establish better methods for handling harmful substances and implementing best practices for managing new, potentially harmful chemicals.

Work on this has begun through the harmful substances focus area of the HEPA Strategic Plan 2022–25, which aims to reduce environmental and human health impacts from legacy contaminants. It will do this through improved treatment and disposal options and environmentally sound management of emerging harmful substances.

For example, all Australian governments are working to implement the Industrial Chemicals Environmental Management Standard (IChEMS).

Released in March 2022 following agreement by all Australian environment ministers, Australia’s industrial chemicals roadmap guides the regulation and management of industrial chemicals.

In NSW, the IChEMS Register is implemented by the EPA under the Protection of the Environment Operations Act 1997.

Certain PFAS chemicals have been added to the IChEMS register and will be prohibited from import, manufacture and export from 1 July 2025.

Future updates to IChEMS will continue to address regulatory gaps as new chemicals are identified.

Image source and description

Topic image:Dharug Country. Close up of contaminated soil being sampled. Photo credit: Bottlebrush Media/EPA (2017).Banner image:Topic image sits above Butjin Wanggal Dilly Bag Dance by Worimi artist Gerard Black. It uses symbolism to display an interconnected web and represents the interconnectedness between people and the environment.

Image source and description

Topic image:Dharug Country. Close up of contaminated soil being sampled. Photo credit: Bottlebrush Media/EPA (2017).Banner image:Topic image sits above Butjin Wanggal Dilly Bag Dance by Worimi artist Gerard Black. It uses symbolism to display an interconnected web and represents the interconnectedness between people and the environment.