Summary

The 2019–20 Black Summer fire season was the most severe ever recorded in NSW, and as the climate warms and dries such fire patterns are likely to become more frequent. Many vegetation communities are now under pressure from too much burning.

Why managing fire is important

Fire is a natural part of the Australian landscape and much of the flora of NSW depends on fire to assist in its reproduction and growth. Altered fire regimes as a result of European settlement – too much or too little fire or fire of too high an intensity – have had a major detrimental impact on the integrity, structure and sustainability of most ecosystems and many threatened species.

NSW indicators

| Indicator and status | Environmental trend | Information reliability |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of mapped vegetation communities exceeding (minimum or maximum) vegetation fire interval thresholds |

|

Getting worse | ✔✔ |

Notes:

Terms and symbols used above are defined in .

Status and Trends

About 7% (5.5 million hectares) of NSW was burnt during the prolonged 2019–20 Black Summer fire season. The total area burnt was four times greater than the previous worst forest fires recorded in a fire season.

Over 450 threatened plant species and 293 threatened animal species occur in the footprint of the Black Summer fires. The prospects of long-term survival of a significant proportion of these species have been impacted by the fires.

Rainforests have a low tolerance of fire and over 300,000 hectares or 37% of all NSW rainforest was burnt during the 2019–20 fire season.

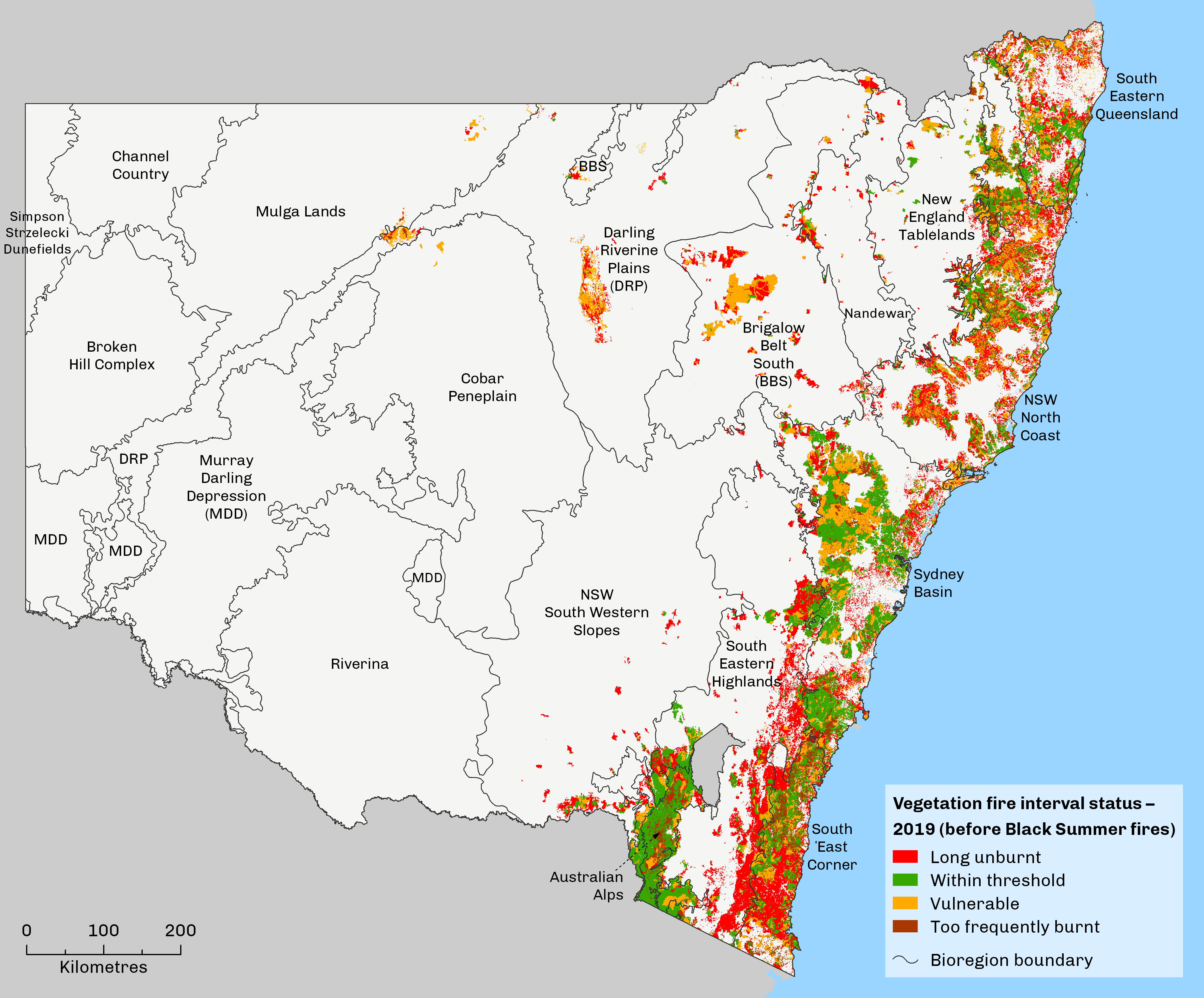

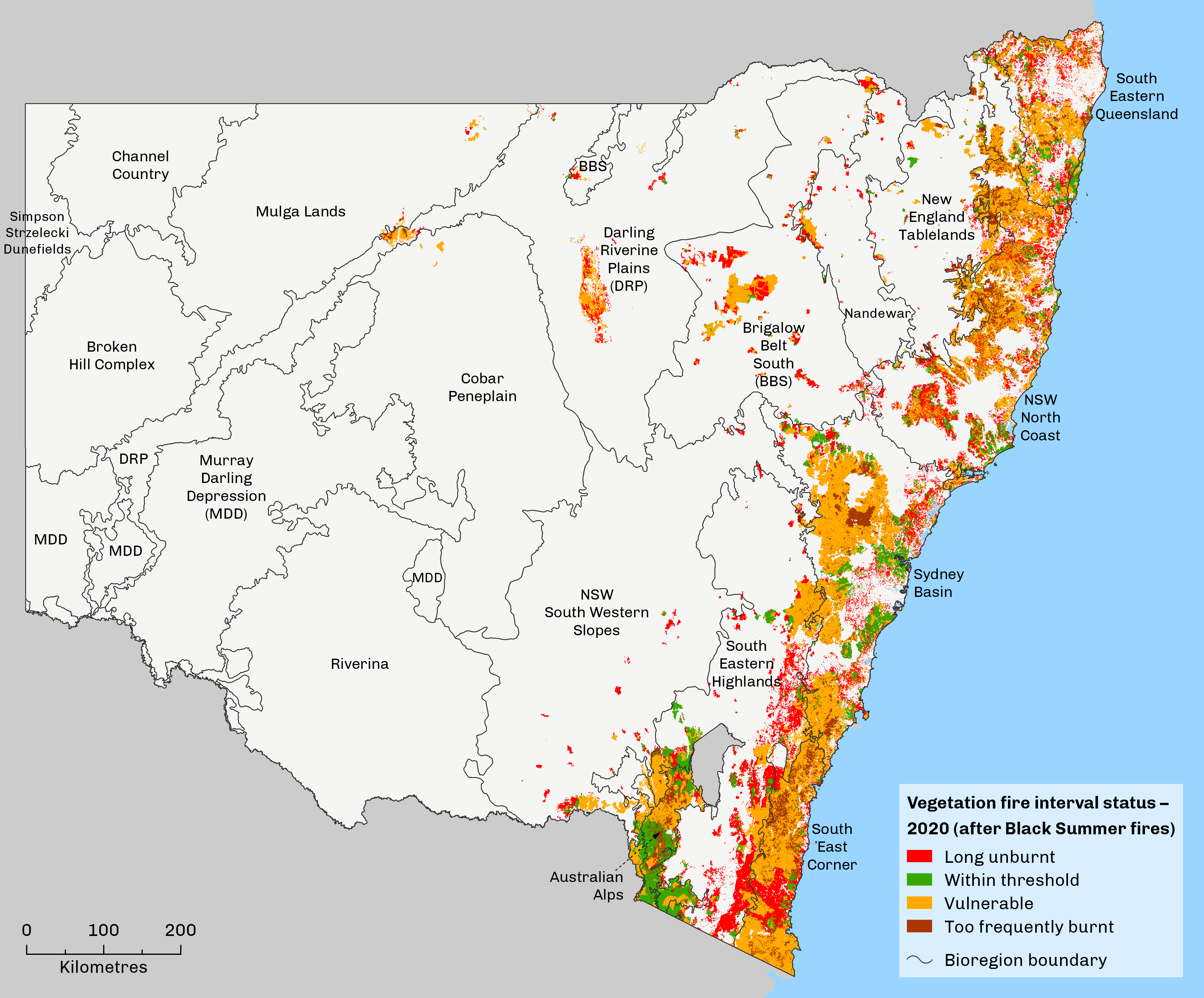

Prior to the Black Summer fires, the fire interval status for vegetation communities was evenly spread – with about third each – within safe thresholds, or under pressure due to being too frequently burnt or insufficiently burnt. Following the fires, about 62% of all vegetation for which recent fire history is available is now under threat from too much burning and only 13% are within thresholds.

Spotlight figure 22: Vegetation fire interval status for 2019 and 2020 in NSW

The Spotlight figure 22 shows the change in status of vegetation fire intervals before and after the 2019–20 Black Summer fires. The time interval between fires is an indicator of the health of vegetation communities, with the recommended time interval, which varies for different vegetation communities, allowing for healthy regeneration and regrowth (apart from some specific communities, such as rainforest, where no fire is tolerated). If the time interval is not within the recommended threshold (i.e. it is too short or too long) this affects the condition and ultimately the integrity of the plant community.

Previously there was an even spread of fire interval status, but now they are strongly weighted towards overburning. This represents a fundamental shift in the ecological condition of vegetation communities and their response to fire.

Pressures

Increasing temperatures and the drying out of south-eastern Australia due to the effects of climate change are leading to longer fire seasons and more severe fire weather.

A trend is emerging for the more frequent development of fire-generated thunderstorms, where fires interact with the atmosphere to escalate the risk and spread of the blaze. Climate change is likely to amplify the conditions leading to the formation of such storms, through increasing dryness and atmospheric instability.

Over half of all bushfires in most years are started by humans, with arson a major cause. However, the Black Summer did not follow the usual pattern, with the majority of fires started by lightning, often in remote and inaccessible locations.

Responses

The key to achieving appropriate fire management is getting the balance right between maintaining natural ecosystems while ensuring community safety and protection of property, infrastructure and livestock.

All 76 recommendations from the NSW Bushfire inquiry announced in January 2020 were accepted by the NSW Government and around $460 million in funding allocated to their implementation in June 2020, including for new bushfire risk management plans, increased hazard reduction works, enhanced rapid response capacity, improved bushfire modelling and upgraded fire trails.

One of the principal tools for fire management is hazard reduction burning. The overall level of hazard reduction has increased over time but is quite variable from year to year, depending on need and favourable conditions.

There is increasing interest in cultural burning, as part of the broader cultural practice of caring for Country in traditional Aboriginal land management. Cultural fire management protects and enhances ecosystems and cultural values, while reducing fuel loads.

Related topic:

Context

Fire has been present on the Australian continent for millions of years and is a key factor in the dynamics of plant and animal populations in most NSW ecological communities. Many Australian plants and animals have evolved to not only survive but also benefit from the effects of fire. Much of the flora of NSW depends on fire to assist in its reproduction and growth.

Fire has been managed since humans first arrived on the Australian continent. Aboriginal people used fire for a range of purposes including cooking, ceremony, hunting, to promote forest resources and as a land management tool. Over time, Aboriginal people developed highly refined and intimate knowledges of fire and used this knowledge to manage Country.

Since European settlement and farming practices, patterns of how fire is managed have changed significantly. Land use and tenure regimes such as urbanisation, industrialisation, agriculture and protected areas have resulted in drastically altered fire regimes and unbalanced ecological systems. Today, these fire regimes and the growing impacts of climate change continue to pose significant hazards to life, property, heritage and the environment.

The principal aim of current fire management is to reduce the risk that fires pose to human life, property and cultural heritage. However, the key to appropriate management is achieving the right balance between ensuring community safety and the protection of property, infrastructure and livestock while maintaining benefits to natural ecosystems and biodiversity and our built, living and historic cultures.

Our populations are living more densely and closer to the fringes of bush settings. With the added pressures of climate change, the types of fires we are experiencing (larger, hotter and more frequent) are changing the way we need to approach fire management. An improved understanding of the role of fire in natural systems is increasingly being factored into fire management through risk-based approaches ().

Status and Trends

Incidence of fire

The effect of bushfires is commonly described in terms of the extent of the fire and its social impacts and costs. Bushfires in Australia can be extremely destructive and may result in substantial social costs, including the loss of human lives, buildings, infrastructure and livestock. Extreme examples include the 2003 Canberra bushfires, 2009 Victoria bushfires and 2019–20 Black Summer bushfires that burnt across large areas of eastern Australia. In these cases, bushfires are natural disasters that have claimed many human lives, destroyed valuable property and infrastructure, severely disrupted essential services and resulted in long-term human health impacts.

Explore these teaching resources for Stage 3 students

The incidence of fire varies greatly from year to year (Table 22.1) with the number of fires closely linked to prevailing weather patterns during the fire season.

Total fire bans may be declared by the Minister for Emergency Services (or under delegation by the Commissioner or a Senior Executive Officer of the NSW Rural Fire Service) in any part of NSW, generally when hot, dry and windy conditions are predicted to occur in areas where vegetation is dry and fire could easily spread.

The 2019–20 bushfire season was the worst ever recorded in NSW. A combination of one of the worst droughts on record, unprecedented weather conditions and intense fire behaviour resulted in over 5 million hectares being burnt across the state. Twenty-six lives were lost and 2,476 homes destroyed. The damage to the natural environment and wildlife was extreme. To put those statistics in perspective, Table 22.1 compares the 2019–20 season to other NSW fire seasons.

Table 22.1: Data on NSW fire seasons, 2002–03 to 2020–21

| Fire season | Bush, grass and forest fires | Hectares burnt | Lives lost | Homes destroyed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002–03 | 5,642 | 1,500,000 | 3 | 86 |

| 2003–04 | 1,764 | 57,600 | 0 | 5 |

| 2004–05 | 2,659 | 16,309 | 0 | 1 |

| 2005–06 | 2,865 | 92,613 | 2 | 13 |

| 2006–07 | 3,361 | 438,218 | 3 | 8 |

| 2007–08 | 2,271 | 85,507 | 0 | 2 |

| 2008–09 | 2,522 | 32,700 | 1 | 0 |

| 2009–10 | 3,446 | 366,159 | 1 | 24 |

| 2010–11 | 2,282 | 37,893 | 0 | 2 |

| 2011–12 | 4,471 | 219,033 | 0 | 0 |

| 2012–13 | 5,885 | 1,400,000 | 0 | 62 |

| 2013–14 | 8,032 | 574,557 | 2 | 227 |

| 2014–15 | 7,837 | 183,677 | 1 | 5 |

| 2015–16 | 7,686 | 87,810 | 1 | 1 |

| 2016–17 | 8,288 | 268,367 | 1 | 65 |

| 2017–18 | 10,036 | 259,720 | 0 | 74 |

| 2018–19 | 9,675 | 288,422 | 0 | 37 |

| 2019–20 | 11,774 | 5,520,000 | 26 | 2,476 |

| 2020–21 | 7,298 | 37,832 | 0 | 1 |

Black Summer fire season

The 2019–20 fire season, also known as the Black Summer fires, was unprecedented in its intensity and scale, running for nine months between 1 July 2019 and 31 March 2020 (). During this season, 11,774 bush/grass fires occurred across NSW, often with numerous fires burning simultaneously (). As a result of the fires, over 5.52 million hectares of land or about 7% of NSW was burnt. The total extent of the area burnt during the Black Summer bushfires was about four times greater than previously recorded in forested areas during any bushfire season in NSW (Table 22.1).

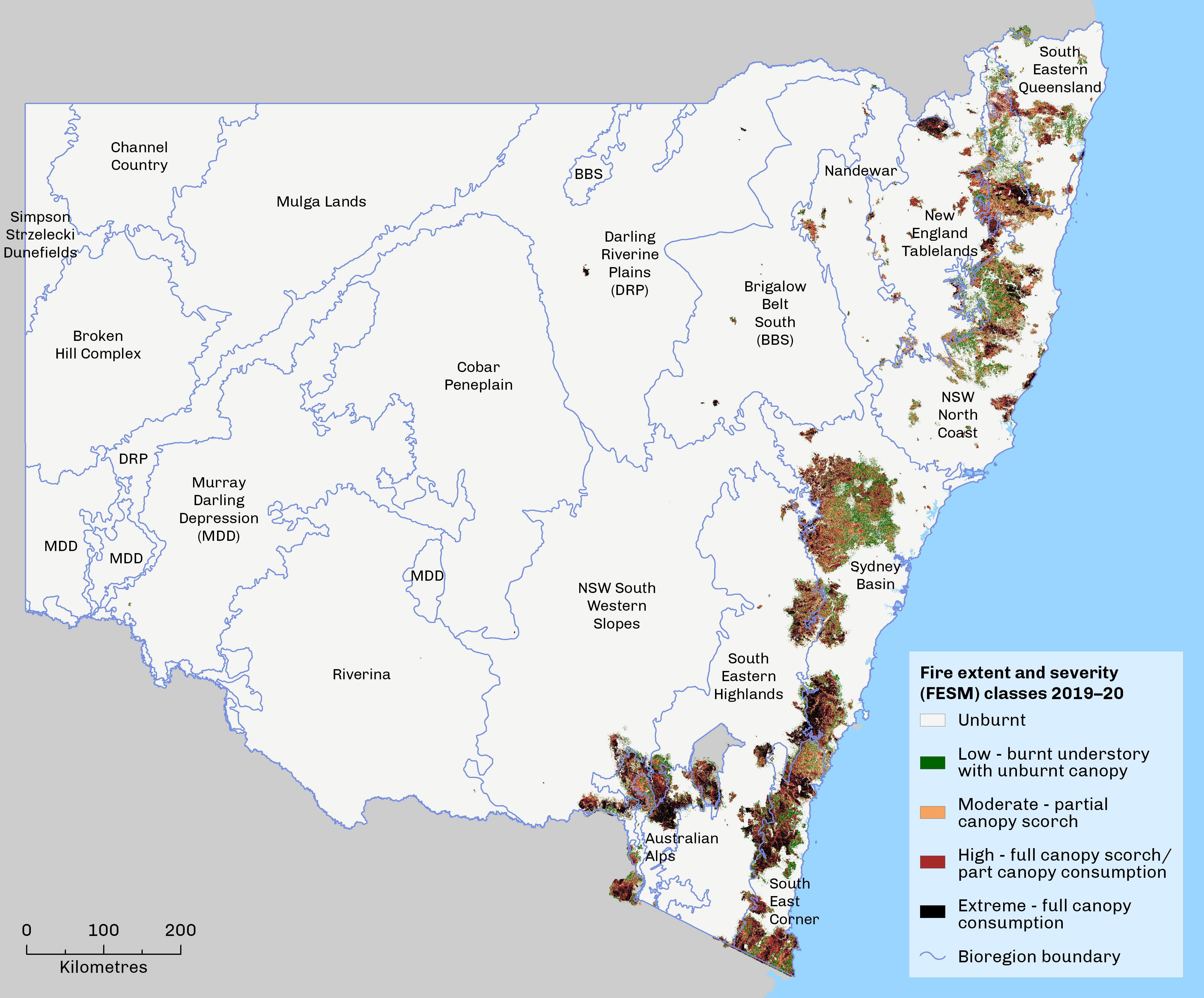

Map 22.1 shows the extent and severity of the fires in NSW in the 2019–20 fire season. Beyond NSW, about 1.5 million hectares were also burnt in Victoria, 86,000 ha in the ACT and 7.7 million ha in Queensland ().

Map 22.1: Fire extent and severity mapping, 2019–20 NSW Black Summer bushfires

The suspected, immediate cause of ignition for most of the largest and most damaging fires during the Black Summer fire season was lightning, often in remote, rugged and/or inaccessible terrain. The dryness of the landscape due to prolonged drought not only enabled lightning to ignite the fires, but also provided suitable conditions for them to spread. Other causes included ember spotting, power lines, deliberate or accidental human activity, machinery and, in some instances, suspected arson ().

The extraordinary scale and intensity of the 2019–20 fire season can be understood by the presence of the four factors leading to serious fire in the landscape:

- spatially continuous fuel

- dryness of the fuel and its availability to burn

- weather conducive to fire spread (high temperatures, low humidity and wind)

- ignition sources.

The Black Summer bushfire season challenged several conventional assumptions about bushfires. It appears that the extreme dryness of forested regions over large continuous areas was a significant determining factor in the size of the fires. When combined with the weather conditions, the fires became extreme, burning through forests and even across bare earth. Previous prescribed burning and hazard reduction activity appears to have reduced fire severity in some instances, but in others it seems to have had no effect, in light of the severity and spread of the fires ().

Fire ecology

Patterns of burning

While the impacts of bushfires are commonly described in terms of areas burnt and lives and assets lost, this provides little information on the ecological effects and consequences of fire on natural systems.

The main factors determining the severity and extent of a bushfire are:

- weather conditions, including wind speed, temperature and relative humidity

- the dryness of the fuel, the type of fuel and the fuel load

- the physical structure of vegetation and the terrain in which the fire is burning

- the effectiveness of fire suppression actions.

More specifically, the ecological impacts of a fire depend on:

- the intensity of the fire

- the season of the burn

- the previous fire history of an area

- the sensitivity of the ecosystems and species affected.

Understanding the ecological effects of fire is limited by the extent of knowledge of the natural responses of vegetation and wildlife to fire. Ecological communities are dynamic systems and fire is a natural disturbance that creates change. Fire shapes the structure, composition and ecological function – including soil and nutrient cycles – of most plant communities, creating the specific habitats required by a range of species. Fire also encourages new growth that provides food for many animals and creates hollows in logs and trees for nesting and shelter. Differing patterns of fire history will favour some species and associations, while suppressing others.

High fire frequencies are known to interrupt life cycles, reduce regenerative capacity, transform habitat structure and increase exposure to invasive species (; ; ). For example, a second fire in too short a time frame could kill all young plants and seedlings before they reach reproductive age and burn off sensitive regrowth, leading to local extinctions. Conversely, the lack of fire may mean that fire-dependent species fail to regenerate. The loss of diversity and function associated with frequent fires is further exacerbated by the shortening of intervals between fires driven by climate change ().

Broad changes in fire patterns may also result in habitat transformations, such as changes in vegetation structure, shifts from one vegetation type to another and reduced habitat resilience to invasion by weeds and feral animals. The specific nature of degradation varies between vegetation community types and depends on the severity of successive fires (both low and high severity fires may have serious impacts, depending on their frequency of recurrence). Many native animals can escape fire to unburnt refuges and recolonise, while insects, reptiles and small mammals may be able to hide underground. However, high severity fires can reduce the number of available unburnt sites and cause a greater number of animal deaths.

Altered fire regimes have been described as a threat to over 80% of the state's vegetation classes (see topic). High-frequency fire has been identified as a significant cause of biodiversity loss in NSW and is listed as a key threatening process under the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016.

Impacts of the Black Summer fires

Aboriginal Culture and Heritage Values

The fires that ravaged NSW resulted in the loss or damage of a significant amount of Aboriginal cultural and heritage values. Aboriginal heritage values include scarred trees, stone arrangements, rock art, artefacts and more. Cultural values can be understood as forest resources, animals or birds that have ancestral and spiritual significance, places of significance such as waterholes, mountain ridges, creeks and forests.

The NSW Aboriginal Land Council observed in its submission (PDF 460KB) to the NSW Bushfire Inquiry:

"We also wish to highlight the mental health impacts on Aboriginal communities as a result the recent bushfires. This trauma has been amplified by the fact that important cultural and sacred sites, homes and livelihoods have been destroyed. Country, trees, plants and animals are intensely significant to Aboriginal people, as a conduit for connecting Traditional Custodians to their culture, country, lore and ancestors. As such, any damage to country causes an immense sense of grief. Aboriginal culture and livelihoods continue to be connected to all aspects of country, including animals and plants" ().

The destruction or degradation of these values as a result of bushfires causes immense trauma and grief within Aboriginal communities and groups.

Plant species and communities

Over 450 threatened plant species, listed under the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 and/or in the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species are known to have been affected by burning. More than 60% of these species are considered at high or medium risk of decline because of impacts of the 2019–20 fires.

Of all high- and medium-risk species, 130 were considered to be at greatest risk of decline, requiring immediate management attention to aid recovery. This priority group were either:

- already listed as Critically Endangered (CR), or

- with a highly restricted range where any decline because of the 2019–20 fires would lead to CR listing, or

- had over 50% of their range burnt and were highly sensitive to some aspects of the fire regime or subject to multiple threats ().

Approximately 640 plant species endemics to NSW but not currently listed as threatened are also expected to have been burnt in the 2019–20 fire season. More than half of these (52%) were found to be at high or medium risk of decline as a result ().

Of the total 114 Threatened Ecological Communities (TECs) under the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Act, 87 were wholly or partly within the footprint of the 2019–20 Black Summer fires. Of those, 15 had more than one-third of their estimated occurrence within the fire footprint and so are at significant risk from fire-related threats that stem from interactions with a series of other threatening processes. These threats include fire-drought interactions, high fire frequency, post-fire impacts of non-native herbivores and predators, fire-disease interactions, high fire severity, post-fire weed invasion, fire-sensitivity of key components, fire interactions with hydrological change, post-fire disturbances and erosion or pollution ().

Animal species and populations

Across eastern and south-eastern Australia around 3 billion vertebrate animals, or 1 billion in NSW are estimated to have been killed, injured or displaced by the Black Summer fires. Due to the lack of baseline monitoring and scarcity of research on the survival of species after fire, these estimates are based on mapping of fire areas and knowledge of animal densities in the areas affected. The estimates are believed to be conservative and exclude some animal groups ().

There are 293 threatened animal species or populations with records in the footprint of the 2019–20 Black Summer fires (). These include:

- all 413 records of the endangered population of yellow-bellied gliders on the Bago Plateau with more than 55% of records in areas where the canopy was partially or fully affected

- four other species or populations with over 80% of their records:

- 97% of records of the critically endangered long-nosed potoroo (fire severity yet to be assessed in these areas)

- 85% of records of the endangered frog (Philora pughi)

- 81% of records of the greater glider endangered population in Eurobodalla and more than 25% in areas where the canopy has been fully affected

- 84% of records of the endangered Hastings River mouse

- 99 species with more than 10% of their records.

Of the 1,074 terrestrial vertebrate animal species recorded in NSW ():

- 18 have more than 50% of their records in the fire ground

- 73 have more than 30% in the fire ground

- 270 have more than 10% in the fire ground.

Vegetation communities

Many Australian vegetation communities or ecosystems are resilient to particular bushfire regimes, including some that tolerate occasional high severity fires. However, the extent and extreme severity of the 2019–20 Black Summer fires, together with the legacies of previous fires, mean that post-fire recovery of some vegetation communities could be slow or completely impeded. The most affected communities by the 2019–20 fires were rainforests (37% of NSW extent), wet sclerophyll forests (~50%) and heathlands (54%) (see Table 22.2).

Table 22.2: Fire intervals for NSW vegetation formations and proportion burnt during the 2019–20 fires

| Vegetation formation | Minimum interval between fires where the focus is managing for biodiversity (years) | Minimum interval between fires where the focus is operational to reduce risk to human life and property (years)* | Maximum fire interval (years) | Within 2019–20 fire ground** | Proportion of NSW total in 2019–20 fire ground** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rainforests | No fire | No fire | No fire | 305,690 ha | 37.26% |

| Alpine complex | No fire | No fire | No fire | 27,410 ha | 20.96% |

| Estuarine and saline wetlands | No fire | No fire | No fire | – | – |

| Grasslands | 3 | 2 | 10 | – | – |

| Grassy woodlands | 8 | 5 | 40 | 221,595 ha | 5.71% |

| Dry sclerophyll forests (shrub/grass sub-formation) | 8 | 5 | 50 | 880,973 ha | 30.80% |

| Dry sclerophyll forests (shrubby sub-formation) | 10 | 7 | 50 | 1,520,489 ha | 29.05% |

| Semi-arid woodlands (shrub/grass sub-formation) | 9 | 6 | 40 | – | – |

| Semi-arid woodlands (shrubby sub-formation) | 15 | 10 | 40 | – | – |

| Arid shrublands (chenopod sub-formation) | No fire | No fire | No fire | – | – |

| Arid shrublands (acacia sub-formation) | 15 | 10 | 40 | – | – |

| Forested and freshwater wetlands (excluding montane bogs and fens, coastal freshwater lagoons and montane lakes with no tolerance of fire) | 10 | 7 | 35 | 140,879 ha | 8.35% of forested wetlands 2.07% of freshwater wetlands |

| Heathlands | 10 | 7 | 30 | 102,969 ha | 53.74% |

| Wet sclerophyll forests (grassy sub-formation) | 15 | 10 | 60 | 1,147,486 ha | 51.24% |

| Wet sclerophyll forests (shrubby sub-formation) | 30 | 25 | 60 | 647,612 ha | 48.81% |

Notes:

* These intervals are absolute minimums for maintaining biodiversity, for asset protection zones within an operational firefighting context, as they provide little or no buffer for adequate seed production.

** Data as at August 2021

Rainforests are among the most fire-sensitive of Australian vegetation communities (Bowman 2000). Much of rainforest fauna is dependent on a moist microclimate and many rainforest plants have no fire-resistant recovery organs and no seed banks to support post-fire regeneration. Over 300,000 hectares, or 37% of NSW rainforests, are estimated to have burnt in the 2019–20 fire season, 14% of them at moderate to extreme fire severity. The burnt areas include approximately 50% of NSW warm temperate and dry rainforests, as well as 25% of NSW subtropical rainforests. This is the largest area of rainforest burnt in recorded history and includes large areas of World Heritage rainforest ().

Like rainforests, the fire tolerance of alpine vegetation is low, with no fire recommended in order to maintain its ecological condition due to organic soils and slow recovery rates (). The Black Summer burnt 27,000 hectares or 21% of NSW alpine vegetation, of which 18% burnt at moderate to extreme fire severity. This added to extensive areas of alpine vegetation still regenerating after severe fires that occurred in 2002–03.

Wet sclerophyll forests are the tallest forests in NSW and the main habitats for much of the bird and mammal fauna of NSW. The 2019–20 fires burnt more than half of the extensive wet sclerophyll forests in NSW at moderate to extreme severity, with around 51% of the grassy sub-formation and 49% of the shrubby sub-formation burnt.

Dense-canopied, mixed shrublands and heathlands are repositories for unique flora and fauna, with more than 90% of their extent burnt in montane parts of the Sydney Basin, including the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area. Over 100,000 hectares of heathlands equivalent to 54% of the NSW total was also burnt ().

Fire intervals for vegetation communities

The interval between fires is a critical factor in the capacity of individual species to survive and reproduce (). The minimum fire intervals needed to maintain a full complement of biodiversity within vegetation communities have therefore been developed for NSW vegetation formations. These allow sufficient time between fires for species to complete the crucial stages of their life cycles essential for regeneration, such as plants being able to reach an age where they can produce adequate seed. Data from Bushfire Hub (See Spotlight Figure 22) shows that 62% of all vegetation with fire history available is under pressure from too much burning following the 2019–20 Black Summer fires.

Table 22.2 presents minimum fire intervals for the range of NSW vegetation formations. It also shows the maximum fire intervals generally tolerable for various vegetation formations, enabling them to regenerate before becoming too old and senescent. The greatest biodiversity is maintained by varying the length of fire intervals between the maximum and minimum requirements as well as the location of fires ().

A key component of long-term monitoring of the effects of fire on ecological systems is matching fire history to vegetation formations. While there are still some limitations due to the deficiencies in the historical data, it is now being collected on an annual, coordinated basis.

Vegetation community types are more specific subgroups of vegetation formations. As a result of the 2019–20 fires, seven NSW rainforest and two alpine vegetation community types, where no fire is recommended, experienced successive fires in less than 50 years across more than 50% of their distributions. Another 20 dry sclerophyll forest, three heathland and four wetland types experienced fire intervals of less than 15 years across over half of their distributions.

Fire interval status

Fire interval status is assessed according to the fire intervals for vegetation formations specified in Table 22.2. Prior to the 2019–20 fires, NSW consisted of a diverse mosaic of vegetation conditions including long-unburnt, too frequently burnt, vulnerable and within the recommended ecological threshold as shown in Map 22.2a.

Map 22.2a: Vegetation fire interval threshold status in 2019 before the 2019–20 NSW Black Summer fire season

In Map 22.2a, the biodiversity threshold status of vegetation communities is classified as:

- ‘long unburnt’ – vegetation communities have not experienced fire for a period longer than the recommended maximum interval

- ‘within threshold’ vegetation has last burnt within the recommended fire intervals.

- ‘vulnerable’ – areas classified as having experienced one fire interval shorter than the minimum recommended interval and/or are in a period where the time since fire is less than the minimum recommended interval (the latter includes all unburnt areas of communities such as rainforest where no fire interval is recommended and all fire is detrimental)

- ‘too frequently burnt’ – vegetation communities have experienced two or more consecutive intervals between fires that are shorter than the recommended minimum interval).

Vegetation communities that are ‘too frequently burnt’ are areas that have experienced two or more consecutive intervals between fires shorter than the recommended minimum interval (). Areas classified as ‘vulnerable’ have experienced one fire interval smaller than the minimum recommended interval and/or are in a period where the time-since-fire is less than the minimum recommended interval. The vegetation ‘within threshold’ has last burnt within the recommended fire intervals, while ‘long unburnt’ areas have not experienced fire for a period longer than the recommended maximum interval.

Map 22.2b shows that following the Black Summer fires there was a substantial change in fire interval status for vegetation in many parts of NSW. The extent of the 2019–20 fires means that very few areas of vegetation now remain in a mature state ().

The Black Summer fires were not limited to the large areas of long-unburnt vegetation present in many landscapes. Many areas that experienced significant fires, such as the Blue Mountains, already had extensive land both within or less than ecological fire thresholds.

Map 22.2b: Vegetation fire interval threshold status in 2020 after the 2019–20 NSW Black Summer fire season

Table 22.3 shows that prior to the Black Summer fires, fire interval status was fairly evenly spread between areas that were long unburnt (under-burnt) - 35.6%; within threshold - 30.1%; and under pressure due to too much burning (too frequently burnt and vulnerable) - 34.6%. It should be noted that only the vegetation within threshold would be considered as being in a healthy condition and receiving an appropriate amount of fire to assist in renewal and regeneration.

Table 22.3: Change in fire interval status before and after Black Summer fires

| Status | Area (sq km) 2019 | 2019 (%) | Area (sq km) 2020 | 2020 (%) | % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long Unburnt | 30,745 | 35.6 | 22,038 | 25.2 | -10.42 |

| Too Frequently Burnt | 6,736 | 7.8 | 9,346 | 10.7 | 2.9 |

| Vulnerable | 2,2954 | 26.6 | 44,831 | 51.2 | 24.61 |

| Within Threshold | 25,997 | 30.1 | 11,410 | 13.0 | -17.1 |

| Total | 86,432 | 87,625 |

Maintaining a burning regime for vegetation that is conducive to conserving biodiversity (within threshold) is a challenge in a fire management framework that is predominantly focused on fire suppression and minimising burning. Prior to the Black Summer fires, there was a balance between areas beyond threshold that were either overburnt or underburnt.

The Black Summer fires caused a significant shift in the status of recommended fire intervals for vegetation (Table 22.3). The majority of vegetation 61.9% is now under pressure from too much burning. A further 25% is at risk due to insufficient burning, while only 13% remains within the optimal fire interval for burning. If any major fire events were to occur in the near future, these might be expected to further distort the balance between too frequent burning and an appropriate level of burning that promotes the maintenance of healthy vegetation communities.

Future cycles of state of the environment reporting should be able to describe fire interval status by individual vegetation formations as set out in Table 22.2, as well as the overall outcomes for all vegetation provided in Table 22.3.

To monitor the threshold status of vegetation biodiversity, complete and accurate fire history data is required across space and time. Multi-decadal fire history and climate data layers are being developed to support future research and development in relation to the 2019–20 fire season in NSW. Currently, the accuracy and coverage of fire history data declines significantly the further back in time it was recorded (). The need for further improvements in technology and training, such as remote sensing for fire management purposes, was addressed in the NSW Bushfire Inquiry and offers opportunities for enhanced monitoring and management.

Hazard reduction

Hazard reduction burning to reduce fuel loads is a key control strategy practised widely across NSW. The burning is complemented by mechanical works, such as slashing undergrowth, mowing, the use of mechanical mulching and bulldozing, to maintain setbacks around properties, firebreaks and fire trails. The annual levels of hazard reduction burning and the total areas of hazard reduction management by land tenure are set out in Table 22.4. These are quite seasonally variable depending on assessed need and suitable weather conditions for hazard reduction burning being available.

Table 22.4: Area of hazard reduction management by tenure in NSW, 2005–06 to 2020–21

| Year | Hazard reduction methods | Land tenure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local council land | NSW national parks | Private land | State forest | Other | Total | ||

| 2005–06 | Burning only | 838 | 29,070 | 3,155 | 38,008 | 790 | 71,861 |

| All methods* | 31,387 | 32,026 | 3,647 | 38,008 | 2,674 | 107,742 | |

| 2006–07 | Burning only | 177 | 23,718 | 8,498 | 37,014 | 1,905 | 71,312 |

| All methods* | 25,495 | 23,840 | 8,892 | 37,015 | 2,295 | 97,537 | |

| 2007–08 | Burning only | 1,163 | 48,497 | 13,958 | 32,474 | 3,861 | 99,953 |

| All methods* | 10,464 | 49,514 | 21,656 | 32,474 | 12,203 | 126,311 | |

| 2008–09 | Burning only | 35 | 59,068 | 8,214 | 24,988 | 7,360 | 99,665 |

| All methods* | 12,304 | 60,117 | 8,897 | 26,632 | 11,364 | 119,314 | |

| 2009–10 | Burning only | 981 | 93,424 | 16,072 | 35,068 | 7,945 | 153,490 |

| All methods* | 16,091 | 95,673 | 16,758 | 35,201 | 9,968 | 173,691 | |

| 2010–11 | Burning only | 396 | 56,060 | 4,734 | 36,931 | 2,811 | 100,932 |

| All methods* | 31,573 | 58,092 | 7,398 | 36,958 | 9,686 | 143,707 | |

| 2011–12 | Burning only | 3,554 | 47,553 | 8,033 | 28,451 | 11,088 | 98,679 |

| All methods* | 34,757 | 49,791 | 9,317 | 28,498 | 24,644 | 147,007 | |

| 2012–13 | Burning only | 1,011 | 207,072 | 11,504 | 20,734 | 11,720 | 252,041 |

| All methods* | 20,310 | 209,594 | 13,220 | 20,773 | 16,900 | 280,797 | |

| 2013–14 | Burning only | 440 | 112,404 | 10,475 | 18,081 | 5,613 | 147,013 |

| All methods* | 16,066 | 114,154 | 10,819 | 18,170 | 8,924 | 168,133 | |

| 2014–15 | Burning only | 428 | 114,343 | 8,628 | 19,422 | 5,444 | 148,265 |

| All methods* | 15,708 | 116,251 | 8,936 | 19,517 | 9,099 | 169,511 | |

| 2015–16 | Burning only | 1,387 | 203,609 | 10,965 | 40,175 | 14,976 | 271,112 |

| All methods* | 14,864 | 205,889 | 11,348 | 40,206 | 19,278 | 291,585 | |

| 2016–17 | Burning only | 755 | 85,032 | 7,175 | 27,173 | 4,973 | 125,108 |

| All methods* | 19,030 | 86,942 | 7,906 | 27,217 | 9,436 | 150,531 | |

| 2017–18 | Burning only | 1,329 | 100,696 | 9,768 | 19,978 | 8,672 | 140,443 |

| All methods* | 14,887 | 102,121 | 10,047 | 20,024 | 11,517 | 158,596 | |

| 2018–19 | Burning only | 439 | 136,157 | 4,470 | 27,423 | 9,442 | 177,931 |

| All methods* | 9,144 | 137,764 | 6,187 | 27,715 | 12,074 | 192,884 | |

| 2019–20 | Burning only | 375 | 27,086 | 978 | 6,618 | 2,972 | 38,029 |

| All methods* | 7,742 | 29,400 | 5,674 | 6,651 | 9,921 | 59,388 | |

| 2020–21 | Burning only | 553 | 53,145 | 95,412 | 8,968 | 9,900 | 167,978 |

| All methods* | 8,191 | 55,967 | 96,016 | 9,043 | 13,274 | 182,491 | |

Notes:

All values in hectares.

*Includes burning and mechanical works, but not grazing of land.

Cultural burning

“Indigenous land management aims to protect, maintain, heal and enhance healthy and ecologically diverse ecosystems, productive landscapes and other cultural values. It is not solely directed to hazard reduction”, ().

Presently, NSW does not adequately support Aboriginal groups to develop and carry out cultural burning initiatives (). This was acknowledged in the final report of the NSW Bushfire Inquiry, with recommendations made to better support Aboriginal groups to conduct cultural burning programs.

In the final report of the NSW Bushfire Inquiry it was acknowledged that:

“The Inquiry heard very clearly from cultural fire practitioners that cultural burning is one component of a broader practice of traditional land management and does not necessarily have fuel reduction as its primary objective. Though hazard reduction can often be an outcome of cultural burning, the Inquiry heard that, more broadly, cultural burning is about caring for country and maintaining healthy and ecologically diverse and productive landscapes. It is also about practising cultural traditions” ().

Cultural burning forms part of a broader cultural practice of caring for Country in traditional Aboriginal land management (DPC 2020). Cultural fire management protects, maintains, heals and enhances ecosystems and cultural values, while also reducing fuel loads ().

There is no prescribed formula for cultural burns. They require delegating responsibilities to the appropriate people, together with respect for Country and recognition of the cultural connection within natural resource management practices. Unlike hazard reduction burning, cultural burns rely on an extensive understanding of local ecosystems to administer generally smaller, cooler and controlled flames ().

Presently, traditional fire practitioners are collaborating with some NSW fire agencies to conduct cultural burns on a small scale. During the 2019–20 Black Summer fires, there were several examples where cultural burning contributed to saving property, notably near Tabulam, Ulladulla, Bundanon and Mangrove Mountain ().

Some recent examples in 2021 of cultural burns on national parks include:

- the Hanwood Cultural Burn conducted in NPWS Wollemi–Yengo Area, hosting more than 60 people partnering with Aboriginal community members, Firesticks Alliance, Hunter Local Land Service and Tocal College. This project supported 40 Conservation and Land Management Cultural Burn trainees to gain hands-on experience in caring for Country through cultural fire management

- a culturally informed burn was conducted in Dharawal National Park. It addressed potential cultural safety issues with an all-women’s fire crew. This culturally informed hazard reduction activity was on Dharawal Country and had an Aboriginal women’s site in the burn area

- a cultural burn was conducted at Diamond Flat in New England National Park. The Cultural Burn Program in the area aimed to bring together communities and staff to share knowledge, build capacity and connections whilst repairing Country.

The current regulatory framework and short-term, project-based nature of funding arrangements for cultural burning activities limit the use of Aboriginal land management ().

In response, the Department of Planning, Industry and Environment is now working with the NSW Rural Fire Service and other government agencies to establish an independent Aboriginal community working group who will:

- preserve the cultural integrity of cultural fire management in NSW

- work to broaden cultural fire management

- establish policies and protocols to ensure cultural safety principles are embedded

- support the development of community-based cultural burning programs ().

On top of this initiative, agencies should be developing relationships with local Aboriginal communities, identifying Traditional Owners with the knowledge of fire management and working with them to plan for and conduct cultural burns in local areas. This includes making provisions for planning, training and equipment to support Aboriginal community members to be present and take part in cultural burning.

For many Aboriginal groups, the intrusions of colonisation have resulted in fragmented and incomplete knowledge systems, especially in regard to cultural burning (). Aboriginal communities should therefore be supported to develop locally appropriate burning programs, and be provided opportunities to support their development and repairing knowledge systems damaged as a result of colonisation and marginalisation of management of their Country. Additional barriers to cultural burning in NSW include uneven and inconsistent community governing arrangements, lack of appropriate training for Aboriginal people to be present on the fire ground and lack of protected equipment ().

Despite these barriers, the NSW Government has committed to supporting Aboriginal groups to pursue cultural burning initiatives. To foster this, agencies and land managers are expected to demonstrate initiative, understanding and support for local Aboriginal groups to reengage with their land management practices including cultural burning.

Pressures

This section discusses the risk factors that exacerbate the threat and impacts of fire on the environment.

Causes of fire

Data has consistently shown that the incidence of fire is markedly higher in the more densely populated areas along the NSW coast than in less densely populated areas elsewhere. There appears to be a strong relationship between the incidence of fire and population density. In the less accessible areas of National Parks, lightning is the main cause of bushfires (lightning caused 42% of fires and 82% of the area burnt in National Parks over the last 10 years).

NSW Rural Fire Service (RFS) data on the causes of fires indicates that more fires are due to human intervention than natural processes (Table 22.5), though a significant proportion of fires throughout the 2019–20 fire season was caused by natural processes (lightning).

Fires due to human intervention may be caused by arson, accidental ignition or escapes from prescribed burn-offs. Prior to the 2019–20 season, arson was the most common cause, responsible for over half of all fires. Investigations by the Australian Institute of Criminology into the causes of 466 fires using NSW RFS data between 2001 and 2004 found that 64% were deliberately lit (; ).

In contrast to the usual pattern of ignition, the immediate cause for most of the serious fires causing the greatest amount of destruction to property and life during the 2019–20 Black Summer fire season was natural. The primary suspected cause for most of these fires was lightning, often in remote, rugged and/or inaccessible terrain. The dryness of the landscape due to prolonged drought not only enabled lightning to ignite the fires, but also provided suitable conditions for them to spread ().

Table 22.5: Causes of investigated bushfires in NSW

| Period | Deliberate (includes juveniles, smoking) | Accidental (includes equipment use, rail, powerlines) | Natural (includes miscellaneous) | Debris burning (includes campfires)* | Undetermined | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010–11 | 174 | 16 | 15 | 31 | 40 | 276 |

| 2011–12 | 110 | 7 | 19 | 16 | 25 | 177 |

| 2012–13 | 307 | 48 | 70 | 96 | 106 | 627 |

| 2013–14 | 257 | 35 | 52 | 83 | 74 | 501 |

| 2014–15 | 154 | 10 | 22 | 27 | 37 | 250 |

| 2015–16 | 187 | 13 | 11 | 16 | 32 | 259 |

| 2016–17 | 208 | 25 | 20 | 34 | 42 | 329 |

| 2017–18 | 239 | 24 | 15 | 35 | 40 | 353 |

| 2018–19 | 147 | 11 | 8 | 19 | 21 | 206 |

| 2019–20 | 114 | 12 | 37 | 18 | 28 | 209 |

| 2020–21 | 49 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 65 |

Notes:

*Redefined from 'burn-off' in previous cycles of reporting

Climate change

The Black Summer fires were the largest recorded in NSW. Unlike previous major fire seasons, the 2019–20 season lasted uninterrupted for many months. It was associated with a record drought before the season, low rainfall during the season and multiple high temperature records (; ). Nevertheless, fires burned under a wide range of weather conditions (temperature, wind speed and direction) ().

The relationship between fire and climate is complex. It involves multiple interacting processes, including both climatic and non-climatic conditions. On average, climate change is making south-east Australia more conducive to bushfires due to:

- an increase in the risk of heatwaves

- longer fire seasons

- trends towards reduced cool season rainfall in the south-east and drought indicators

- variations in key drivers of climate (ENSO, Indian Ocean Dipole and Southern Annual Mode)

- conditions that encourage fire-generated thunderstorms

- an increased number of incidences of fire ignition by dry lightning.

In December 2019, the Forest Fire Danger Index (FFDI) and Fuel Moisture Index (FMI) both reached record-breaking levels in NSW. These climatic conditions combined with extreme high temperatures and low precipitation to create widespread high levels of fuel dryness and fire weather (). The unprecedented FFDI and FMI records were later matched by the massive fires, exceeding records for the area burnt and the number of extreme pyroconvective events.

The 2019–20 FFDI readings in NSW were consistent with climate change projections a decade earlier predicting an increase by 2020 in the frequency of days with ‘extreme’ FFDI values by 5%–25% for low climate change scenarios and 15%–65% for high climate change scenarios (; ). Under the same modelling, 2050 FFDI values are forecast to rise by 10%–50% for low climate change scenarios and 100%–300% for high scenarios ().

The factors manifest in the 2019–20 Black Summer demonstrate how the unprecedented could become the norm in future NSW fire seasons (). If current climate trends continue, the fire weather conditions experienced during the 2019–20 fire season will become increasingly likely (). Already, the fire season can arrive up to three months earlier than in the mid-20th century (). Research also indicates that there has been an increase in the number of dry lightning events in coastal NSW since 1979, the leading natural ignition cause of bushfires ().

Changes in fire weather

Fire weather and resultant fire behaviour is driven by climate cycles and these can vary from year to year.

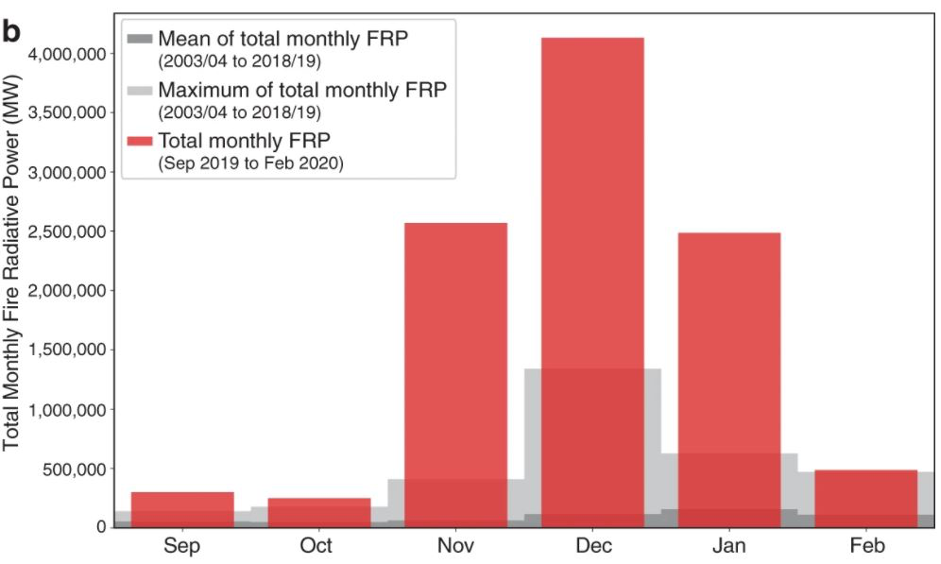

Prolonged drought conditions driven by a positive Indian Ocean Dipole and Southern Annual Mode led to the most severe and widespread fire season recorded in NSW in 2019–20. The weather and fire extremes are illustrated in Figure 22.1 which shows the Fire Radiative Power in south-eastern Australia from November 2019 to January 2020 far exceeded both the average and maximum total of any month from 2003–04 to 2018–19.

Figure 22.1: Fire Radiative Power chart

Notes:

FRP – Fire Radiative Power.

Data underpinning figures from work by individual scientific researchers is not available for interactive display.

This research demonstrated that FFDI from June 2019 to February 2020 was at least two and in some cases six standard deviations above the average, highlighting the extremity of the season.

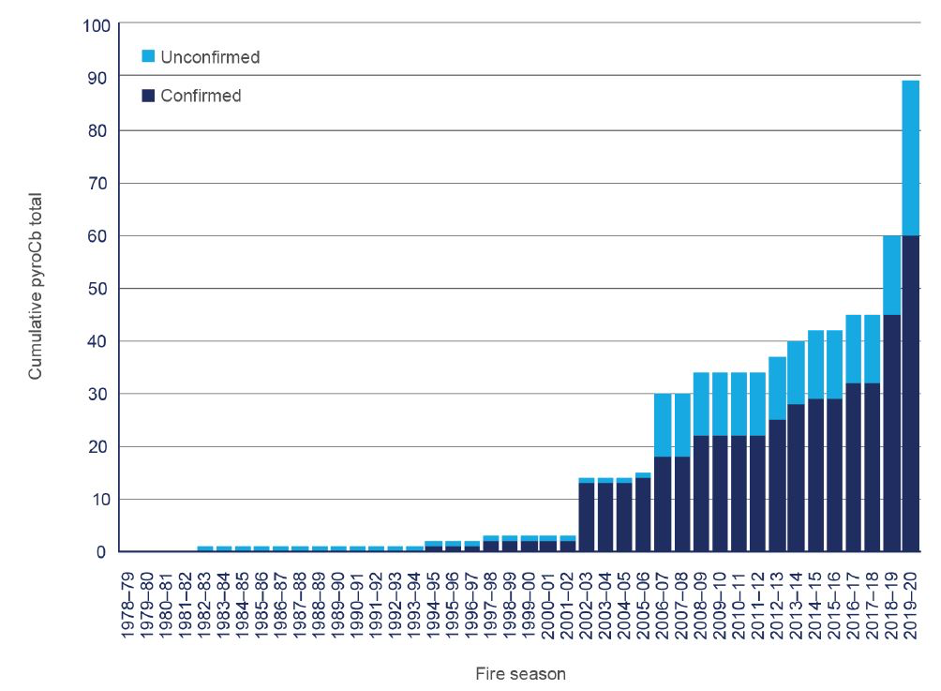

Another notable feature of the 2019–20 Black Summer bushfire season was the unprecedented high occurrence of fire-generated thunderstorms, also referred to as pyroconvective or pyrocumulonimbus (pyroCb) events. PyroCb events are a relatively rare weather phenomenon which appear to be becoming more frequent. Pyroconvection occurs when a fire releases large amounts of heat energy into the lower atmosphere, causing changes in wind speed and direction and creating conditions like those that drive thunderstorms. The storm behaviour substantially escalates the fire risk, affecting the rate and direction of its spread as fire fronts become more volatile and unpredictable. The fire, in effect, creates its own weather conditions that help to propagate the blaze, including through further lightning strikes. These events challenge the traditional understanding of fire spread and create hazardous conditions for firefighting.

Thunderstorms develop when the right mix of atmospheric instability, dryness, topography and vegetation type and surface fire weather conditions combine (). They have been shown to coincide with increases in dangerous surface weather as measured by FFDI (). Climate change could amplify these conditions by increasing atmospheric dryness and instability ().

Watch: fire-generated thunderstorms explained (3.55 minutes)

The cumulative total of events in south-eastern Australia recorded since the satellite record began in 1978 is shown in Figure 22.2 (). During the 2019–20 fire season, the total pyroCb events recorded increased from 60 in total up to 2018–19 to almost 90 by the end of 2019–20, a 50% jump during the one fire season.

Figure 22.2: Cumulative number of recorded pyroconvective events in south-eastern Australia, 1978–79 to 2019–20

Notes:

Data underpinning figures from work by individual scientific researchers is not available for interactive display

In addition to the unprecedented number of pyroCb events recorded in the Black Summer, the 2021 fire season in the northern hemisphere has already produced new records for pyroCb events. This global pattern of extreme fire activity shows how the planet is responding to human-induced climate change (see topic).

PyroCb events can have broader harmful effects for people and the environment. For example, smoke and ash in the atmosphere are known to cause serious disturbances to the global climate, resulting in crop failures and food shortages. Research indicates that the amount of smoke particles injected into the lower stratosphere from the 2019–20 super-outbreak rivals or exceeds that of all volcanic eruptions observed between 2012 and 2020 ().

Responses

Legislation and policy

Rural Fires Act 1997

The NSW Rural Fire Service (RFS) is the lead combat agency for bushfires in NSW. Under the Rural Fires Act 1997, the NSW RFS is responsible for preventing, mitigating and suppressing bushfires in rural fire districts. Under the Act, the RFS is to have regard to the principles of ecologically sustainable development described in section 6 (2) of the Protection of the Environment Administration Act 1991 in carrying out any function that affects the environment.

The Rural Fires Act 1997 provides for the establishment of the NSW Bush Fire Coordinating Committee and Bush Fire management committees which prepare and adopt Bush Fire Risk Management Plans for their areas.

The risk management plans identify assets at risk from bushfires, including environmental assets, and specify a range of strategies and actions to protect these assets and the agencies responsible for their implementation. Strategies include fuel management, ignition prevention and community preparedness and response. The NSW RFS has also commenced implementation of a new risk management planning process, including new risk plans developed by local Bush Fire management committees.

National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974

The National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 specifies requirements for the management of reserved lands and lands managed by the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS). Fire management in these areas must follow the management principles outlined in the Act, such as minimising the risk of extinction and maintaining biodiversity.

As a manager of public land, NPWS has obligations under the Rural Fires Act 1997 and is accountable for taking practicable steps to prevent the occurrence of bushfires on its estate and also minimise the danger of the spread of bushfires on or from its estate. NPWS has the largest paid bushfire fighting force in NSW and plays a critical role in the management of fire, including responding to bushfires and undertaking hazard reduction activities.

NSW Bushfire Inquiry

In January 2020, the NSW Premier announced an inquiry into the 2019–20 bushfire season to learn from experience and make recommendations in relation to bushfire preparedness and response.

The NSW Bush Fire Inquiry made a total of 76 recommendations (), all of which were accepted by the NSW Government. A range of initiatives are underway in response to the inquiry recommendations, backed up by a $268.2 million funding allocation in the NSW Budget in June in addition to earlier funding of more than $190 million following the inquiry.

Resilience NSW is coordinating the response and is currently monitoring and reporting progress against a total of 148 recommendations and sub-recommendations, which a range of different agencies are responsible for delivering. The NSW RFS is the lead agency for about 79 recommendations and sub-recommendations, while NPWS is responsible for 16.

The most significant recommendations NPWS is committed to include:

- enhanced fire suppression capacity with an extra 125 firefighters recruited and trained and another helicopter available for hazard reduction burns and rapid bush-fire response

- an acceleration in the upgrade of the state’s fire trail network, $125.9 million allocated over four-year (2019–23)

- an increase in hazard reduction activity in high-risk asset protection and strategic fire advantage zones

- improved identification and risk management of environmental assets by a bushfire risk and evaluation team established to complete this work.

At 30 June 2021, 99.3% of the recommendations Bushfire Inquiry were completed or in progress, while one was being scoped.

Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements

The Commonwealth Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements was established in February 2020 as a response to the extreme bushfire season of 2019–20. It focused not only on the 2019–20 bushfires, but also examined other rapid onset events that cause serious disruption to communities or regions, such as floods, storm surges or earthquakes.

The Royal Commission examined, among other things:

- the responsibilities of, and coordination between, Australian, state, territory and local governments relating to natural disasters

- Australia’s arrangements for improving resilience and adapting to changing climatic conditions

- what actions should be taken to mitigate the impacts of natural disasters

- whether changes are needed to Australia’s legal framework for the involvement of the Commonwealth in responding to national emergencies.

The commission released its report in October 2020 ().

Programs

Fire management

The principal aim of fire management is to reduce the risk that fire poses to life, property, infrastructure and environmental, economic, cultural, agricultural and community assets.

The approach to bushfire risk management in NSW is coordinated on a multi-agency basis. The planning and prioritisation process is a highly strategic exercise intended to achieve the best possible protection outcomes with the resources available and limited windows of opportunity. While the legal obligation to carry out designated hazard reduction rests with the landowner or manager, the NSW RFS provides assistance in undertaking hazard reduction works.

Where bushfire risk reduction requires high modification to vegetation, environmental assessments are conducted to understand the impacts of the intended works and manage the biodiversity risks. However, compromises that result in suboptimal outcomes for biodiversity conservation may be required at times (), particularly in asset protection zones (see Table 22.2). Appropriate assessment is undertaken on a case-by-case basis in these circumstances.

Sustainable fire regimes aim to maintain and improve conservation outcomes, as outlined in the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974. Improved fire metrics incorporating inputs such as fire severity and frequency in representative ecosystems, are being developed currently by NPWS and research partners. This work will better inform conservation land managers on the appropriate application of fire regimes, particularly post 2019–20 bushfire impacts.

Cultural burning

Amongst the recommendations put forward by both the NSW Bushfire Inquiry and the Royal Commission was that cultural burning is but one component of a larger practice of Caring for Country, and Aboriginal people should be supported to pursue Caring for Country as holistic practice. The NSW Government has formally adopted this policy.

DPIE is coordinating a statewide response to the bushfire inquiry including developing a NSW cultural burning strategy. This strategy, designed under the stewardship of an expert Aboriginal cultural burning advisory group, will develop a set of guidelines and principles for cultural burning on NSW lands, including cross-tenure land management.

Bushfire Risk Management framework

A comprehensive bush fire risk management framework currently exists in NSW, supported by legislation and the Bush Fire Coordinating Committee (BFCC) Policy. This framework provides for the development of Bush Fire Risk Management Plans by the multi-agency Bush Fire Management Committees (BFMC) set up throughout the State. There have been significant recent advances in technology, fire spread modelling, quantitative risk assessment and the availability of spatial data, which will inform the development of an enhanced bush fire risk management framework for NSW.

In response to the Final Report of the NSW Bush Fire Inquiry, the process of rolling out the next generation of Bush Fire Risk Management Plans across NSW commenced in 2021. It will allow BFMCs to better focus on prioritising treatments and protecting community assets from bush fire. The development process is interactive and includes a series of BFMC meetings and workshops, facilitated by the NSW Rural Fire Service and supported by National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) and Forestry Corporation of NSW. The complete roll out of the new generation plans is expected to be a three-year program.

Hazard reduction

Hazard reduction is an important risk management strategy that helps address the threat of fire for people living in over 1.4 million properties situated on 48 million hectares of bushfire-prone land across NSW. It is part of a multi-faceted strategy for managing bushfire risk that also includes building design, defendable space, community education and fire suppression.

Within that context, the specific objective of hazard reduction works is to reduce fuel loading to a manageable level, with a view to generally reducing the spread and intensity of bushfire. Importantly, hazard reduction – no matter how comprehensive – does not (and cannot) eliminate bushfire risk entirely.

Hazard reduction works include a range of treatment methods which may be employed either in isolation or together. The principal treatment methods are prescribed burning and mechanical or manual removal of fuels using heavy machinery, hand-held tools and/or spraying. It may also involve other methods including, for example, grazing.

The ability of NSW RFS and partner agencies including NPWS, Forestry Corporation of NSW, Fire and Rescue NSW and Local Councils to complete hazard reduction works (particularly prescribed burning) is highly dependent on weather, with opportunities consequently limited and unpredictable. Longer fire seasons have further reduced the opportunities for hazard reduction burning in recent years and prolonged drought conditions have also complicated the conduct of prescribed burning as drier fuel loads trigger more erratic fire behaviour.

Nevertheless, to make the best use of all available windows of opportunity for hazard reduction burns, the NSW RFS and land management agencies conduct strategic preparatory work to ensure maximum readiness when the weather is favourable.

Bush Fire Environmental Assessment Code

The updated Bush Fire Environmental Assessment Code () provides a streamlined environmental assessment and approval process for bushfire hazard reduction works. Assessments under the code consider the impacts of prescribed burning and mechanical works on natural values, including vegetation, threatened species, heritage items, soil stability, and air and water quality.

Minimum fire intervals for vegetation formations (see Table 22.2) and threatened species guidelines are both incorporated as standards for the protection of biodiversity.

Enhanced Bushfire Management Program

The Enhanced Bushfire Management Program (EBMP) in 2011 was funded by the NSW Government in response to the findings of the 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission to prepare for a potential increase in the threat of bushfires. Although originally funded until 2017 with a commitment of $76 million, the program has since been extended to 2022 with a further $92 million commitment.

The program aims to increase the level of hazard reduction works conducted annually and improve bushfire response capability in parks and reserves. A key component is the establishment of teams across the state to conduct hazard reduction works and respond quickly to outbreaks of fire in remote areas.

Since the start of the Enhanced Bushfire Management Program in 2011, and specifically between 2012–13 and 2020–21, NPWS has undertaken 79% of the total hazard reduction burning in NSW, often in collaboration with NSW RFS and other agencies. (The overall total excludes stubble grass burning by private landholders on non-fire management zoned private tenure during the 2020–21 fire season). Consistent with the NSW Bushfire Inquiry’s recommendation to adopt an approach that is strongly guided by risk reduction, the current NPWS hazard reduction program is focused on reducing fuel in the areas of highest risk: strategic fire advantage zones and asset protection zones.

Fire access and fire trails

NPWS manages a fire trail network with around 40,000 kilometres of roads and trails, including over 31,148 kilometres of fire trails that are used for hazard reduction work and bushfire suppression activities. During 2020–21, NPWS delivered $30 million of fire trail upgrades and maintenance, resulting in 618 kilometres and 20 bridges upgraded to standards and a further 2,110 kilometres maintained to ensure open and safe access. These improvements ensure safety, strengthen the capability of firefighters to combat bushfires and ensure that emergency services personnel have improved access to protect homes and properties.

Forestry Corporation of NSW manages road and fire trial network of 60,000 kilometres and makes significant annual investment in maintaining its network.

Rapid response to remote area bushfire ignitions

The early detection and rapid suppression of bushfires is a key control strategy for managing and preventing their spread, particularly when fires start in remote areas. To enable a rapid response and minimise the spread of fires, special remote area fire teams (RAFT) and rapid aerial response teams (RART) have been set up by the NSW RFS and the NPWS as part of EBMP. The RART have specially trained and equipped personnel with dedicated helicopters on standby to enhance the capacity for early detection and rapid suppression of fire.

Remote area and aerial responses are recorded and tracked to measure performance against objectives and key performance indicators (KPIs). The NSW RFS and NPWS teams have KPIs to keep 80% of bushfires to less than 10 hectares in size and respond to 90% of fires within 30 minutes. Since the NPWS RART program began in 2012–13, 91% of all bushfires involving aerial operations have been responded to in less than 30 minutes and 83% of bushfires involving aerial operations have been contained to less than 10 hectares.

Since 2011, 85% of all fires that started on national park land have been contained within the park and 68% of all park fires (with or without aerial operations) were kept to less than 10 hectares in size.

The NSW Bushfire Inquiry recommended that NPWS and NSW RFS continue the highly successful rapid response program to suppress remote ignitions throughout the landscape.

Forestry Corporation NSW manages two million hectares of public land and prioritises early fire detection and rapid response to fires. Forestry Corporation NSW maintains a highly trained firefighting workforce, a network of fire towers and a fleet of light firefighting vehicles, tankers and heavy plant that can be readily deployed to firefighting. Forestry Corporation is also investing in trialing fire detection technology.

Enhanced aviation capability and technology

Prior to 2021, the NSW RFS aviation fleet comprised one Large Air Tanker (LAT) and six helicopters used for aviation search and rescue and fire fighter transportation, including the deployment and extraction of Remote Area Firefighters. In 2021, the fleet was expanded with the addition of two Citation fixed wing aircraft. These fast jets will be used for lead plane operations, scanning and passenger transport, with their scanning capabilities enhancing the integration of these aircraft with LAT operations. Historically, the lead planes’ primary role was to guide the LAT into the retardant drop zone. The Citations will also assist with gathering fire intelligence, impact assessments, search operations and vegetation mapping.

Forestry Corporation NSW contracts private aerial firefighting support to be on standby and support initial firefighting response each fire season. Forestry Corporation NSW has also increased the use of drone technology in firefighting over recent years, with thermal imaging drones used to identify, map and monitor fires and enhance data collection and decision making in active firefighting.

Planning and land use

Land-use planning decisions are intrinsic to fire management and environment protection strategies.

Integrating protection against bushfires into the planning and development system through compliance with the regulatory framework set out in Planning for Bush Fire Protection () ensures safer developments in bushfire-prone areas. A revised version of the document was published in 2019, incorporating the latest science and best practice.

Strategies include providing emergency access and evacuation roadways and upgraded water supplies and requiring bushfire protection measures for buildings with developments set back from bushland at the planning stage to protect dwellings from fires. Higher building construction standards may also be adopted to offset the setback distance required.

As a plantation manager, Forestry Corporation NSW reviewed the fire resilience of timber plantations and developed guidelines for fire-resistant plantation design.

Community engagement

Community engagement activities and resources are a key component of the bushfire risk management program. The NSW RFS continues to promote ongoing public awareness activities about community preparedness for fires. A new public awareness campaign for the 2021–22 bushfire season highlights the need to plan and prepare for fires and stresses that individual preparation actions are important for the protection of the community as a whole.

Local engagement continues to be key to the success of communicating risk and improving the levels of engagement, especially through brigade-led activities. One of these is the annual Get Ready Weekend, during which RFS brigades educate their communities about the local bushfire risk and associated actions to make their home safer, as well having a bushfire survival plan ready.

Other community engagement programs include the Hotspots Fire Project with state agencies and non-government organisations providing landholders and land managers with the skills and knowledge they need to protect life and property as well as maintaining biodiversity. The project promotes the understanding that well-informed and prepared communities complement the roles of land managers and fire agencies.

The NSW RFS AIDER program assists infirm, disabled and elderly residents living in bushfire-prone areas undertake fuel reduction activities.

Arson prevention

A range of measures has been implemented to reduce the rate of arson in NSW. Information sharing between agencies responsible for preventing and investigating arson-related fires has vastly improved, through establishment of the Bushfire Arson Taskforce and a whole-of-government intelligence database. The development of cross-agency strategies by arson prevention district working parties has also reduced the incidence of arson-related fires in those areas where they have been detected. NSW will continue to support the National Strategy for the Prevention of Bushfire Arson implemented in 2009.

Knowledge and information

The Bushfire Risk Management Research Hub for NSW brings together researchers, fire agencies and public land managers to develop new understandings that will underpin cost-effective strategies that reduce the risk fire poses to people, property and the environment.

The hub’s data repositories and management systems to date have seen updated and consolidated fire histories are available for mapping fire history and fuel load inputs the Phoenix fire simulation software and departmental databases. There have also been updates to the Fauna Fire Response Database and the draft interim Threatened Species Hazard Reduction List that is used by fire management agencies to plan prescribed burns.

‘Guardian’ is replacing the Bushfire Risk Information Management System (BRIMS) and will significantly improve the way all bushfire risk mitigation activities are undertaken. It will also include a public portal that may assist individuals in analysing the risk associated with their property and identifying actions that can be taken to mitigate this risk.

Guardian stores data on fires across the state and is maintained by fire authorities and public land managers. Long-term data on where fires start and how they spread will be invaluable for determining fire management strategies, the allocation of firefighting resources and the prevention of fires caused by arson and accidental ignition. Collated data on prescribed burns will also provide greater insight into how fire history affects fire management and environmental impacts.

Australian Fire Danger Rating System

To meet future fire management and communication needs, NSW is leading the development of the Australian Fire Danger Rating System (AFDRS), which is due to be operational for the 2022–23 fire season. The AFDRS uses the latest scientific understanding about weather, fuel and fire behaviour in different types of vegetation to improve the reliability of fire danger forecasts. This enables those working in emergency services to be better prepared, make improved decisions and provide better advice to the community. The system will be adaptable to take advantage of improving science, data, and information into the future.

The way that the fire danger rating system is presented to the community will be consistent in every state and territory in Australia, reducing the possibility for confusion. The new ratings system will have fewer levels, use logical colours, and simple English terms to improve people’s comprehension of both the system and their personal risk, providing concise messages to encourage people to take action to protect themselves and others in the face of bushfire risks.

Future opportunities

Fire management strategies will increasingly be based on better knowledge of fire behaviour and ecology and better techniques for fire suppression.

There is scope for better maintenance and use of the data and information that is collected about fire. Information is improving, leading to more sophisticated analyses of bushfire patterns, effects and environmental impacts and the use of decision-support and related technology, such as digital mapping systems for fighting fires and managing hazards.

Support for new and ongoing research is essential for all aspects of fire behaviour, management and suppression. There is a need to learn more about fire ecology and how to improve building design, property management and community resilience to better cope with fire.

There are opportunities to further expand the development of cultural burning programs throughout NSW. by supporting local agencies such as RFS brigades and NPWS offices to enhance local relationships and promote and develop cultural burning programs and Aboriginal land management within local regions.

The incidence of high fire-risk days – and consequently the frequency of bushfires – is expected to rise. The number of days when it is appropriate to conduct hazard reduction burning may be reduced or move to earlier and later in the year. Under such scenarios, fire management strategies will need to be flexible and informed.